Haven Kimmel’s book is only the beginning of strange tales from Indiana

One afternoon about 30 years ago, my mother found a young Hampshire pig in our woods and carried it to the house in hopes we could reunite it with the owner. Yet, when Mom put the pig down she realized that she had seen only its good side. In fact, the pig had been badly injured. It was missing an eye and one side of its body was infected. So Dad came out of the house and shot the pig with a .38, and then we all sat down to a spaghetti dinner, which was interrupted when the pig began stumbling around the yard. Dad got up from the table, went outside, and shot the pig several more times, then returned to finish his meal.

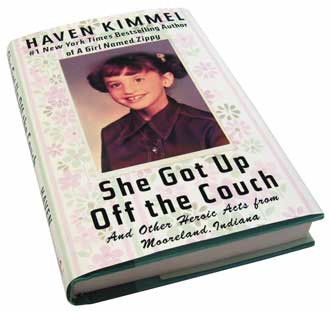

Such is life in Henry County, Indiana, where among the cornfields and fencerows Haven Kimmel’s new, humorous, and occasionally treacly memoir She Got Up Off the Couch (the sequel to the best-seller A Girl Named Zippy) recounts her childhood in a small Hoosier town while tracing her mother’s journey from subjugated couch potato to self-possessed schoolteacher.

Although I never knew Kimmel, she and I grew up 20 miles apart in Mooreland and Mechanicsburg respectively, microscopic hamlets connected by Highway 36, a route favored by April tornados and truckers eluding interstate speedtraps. She and I grew up in the 1970s and early ’80s when women and girls, especially in podunk America, were not yet seen as equals of men and boys.

| SHE GOT UP OFF THE COUCH By Haven Kimmel Free Press $24, 302 pages ISBN 0743284998 |

Many aspects of our lives were similar: Our fathers worked at Delco-Remy, our mothers had been cheated out of opportunities, and we both drank well water and hated canning season. In other ways, our experiences couldn’t have been more different: she, the youngest of three, poor, with a sunny, if self-deprecating, disposition and a distant father; I, the oldest of three, middle-class, with gallows humor and a loyal dad.

Like that Hampshire pig, life was pure on one side, festering on the other. Which is not to say that either of us had it particularly bad or particularly good. Only that we had it weird.

“‘Nothing stops her,’” Kimmel’s father says in the book. “Nothing, he meant, as in no money, no driver’s license, no teeth, no job, no support, no supplies, no safe car. And nothing he meant, as in himself.”

For 27 years, Kimmel’s father had squashed his wife’s aspirations, but this was not uncommon. Feminism wasn’t a cultural norm in Henry County, and subversives who espoused such notions were considered tomboys, lesbians, hussies or worse, supporters of the Equal Rights Amendment. Yet, under these conditions, one day Kimmel’s mother, 268 pounds wearing an enormous orange dress and shoes stuffed with newspaper, wrapped her hair in a bun (“Dear God, I look like a drunken school bus,” she said), stopped being her husband’s accomplice, and with 86 cents in her purse drove a temperamental Plymouth 30 miles to take a college-entrance exam — on which she tested out of her freshman year at Ball State University. It seemed as miraculous as the virgin birth, the ultimate feminist act.

| Author Haven Kimmel and Lisa Sorg grew up 20 miles apart in the 1970s in rural Indiana where only hussies were feminists and their mothers had to wait decades to come into their own. |

But to enter college, you must graduate from high school, and my mom, a bright if rebellious student, could not. In the summer of 1964, then 17, she and my father, 21, decided to marry. The notice of their marriage license appeared in a local newspaper and shortly thereafter my mother was summoned before a special meeting of the school board. She had only two classes left in order to graduate, but neither that nor a sense of justice dissuaded the board from expelling her for fear she might tell other students about sex. Never mind that boys could marry. Boys could breed. Boys could stay in school. My mother never earned a high-school diploma or a GED, but she has a happy, productive life anyway. Yet I’ve often thought about what might have been. She’s a natural teacher, and taught her children to read well before they entered kindergarten. She could have molded the minds of thousands; instead she inspired only three.

In rural Indiana, where the nearest legitimate grocery store could be 20 miles away, a car symbolizes the ultimate liberation. At 21, my mother didn’t have a license because the summer of her junior year when her school offered driver’s ed, she worked picking strawberries. Living in a single-wide with two kids under age 3 and a husband on the night shift, she decided it was time to learn. Dad taught her to drive a stick shift in a ’64 Impala and my 6-month-old brother surely suffered from mild whiplash as his tiny, weak neck snapped back and forth. However, my mom turned out to be an excellent driver. One night several years later, she unexpectedly stopped at a dark railroad crossing. Out of nowhere roared a train, which had she not braked, would have surely killed us. I later learned she’d had a premonition and had been praying.

| “No man would keep ME from driving a car, forget it! What is this, a Turkish prison? What do you do all day, just sit around watching the %*#$ TV?!” |

When Kimmel’s mother made the trip to the college exam, she didn’t know how to drive — all the more astonishing because she would have had to have traveled on bona-fide four-lane highways to get there. Without transportation, Kimmel’s mother’s world extended no farther than Mooreland’s three streets and the fantasy worlds in her science-fiction books and soap operas. The Kimmels’ new neighbor, Bonnie, a tomboy, hussie, perhaps a lesbian, and certainly an ERA supporter, stops by to teach Kimmel’s mother to drive Bonnie’s VW bug; she also offers an expletive-ridden lesson in feminism: “No man would keep ME from driving a car, forget it! What is this, a Turkish prison? What do you do all day, just sit around watching the %*#$ TV?!”

Kimmel’s mother replies demurely before heading out the door: “This is actually a Christian household and we try not to use such language.”

Fuck that. We cussed. Incessantly. And definitely while driving. During Sunday political talk shows it was typical for my parents to bellow “cocksucker” or “motherfucker” at the television, usually when Democrats were on. (As a political aside, Kimmel recalls seeing a John Birch Society sign posted along Highway 36; my parents received the JBS newsletter.) My dad once told me if I wanted sympathy to look between “shit” and “syphilis” in the dictionary. However, my mother is a better cusser than my dad, probably because she’s never worked outside the home.

Over time, Kimmel’s mother loses more than 100 pounds, earns a master’s degree, works as a teacher — and, most importantly, becomes her own woman while her husband fades from the family picture. Although my mother was never as oppressed by my father, she, like many woman of that era, finally came into her own after age 40, if that only means she does what the hell she pleases. And now, if a wounded Hampshire pig wandered into the yard, she could shoot it herself. •

By Lisa Sorg