"Today its grim walls, scarred and battered in that heroic struggle for liberty, stand threatened by vandalism and menaced by the hand of commercialism."

It seems impossible that this could be written about any building in San Antonio. Few cities prioritize historic preservation so much, and if any structure were to be protected, it would surely be the Alamo.

But the quote is part of a 1903 pitch from the Daughters of the Republic of Texas to raise money to save the Shrine of Texas Liberty from ruin. It's unfathomable that such measures were necessary, given that the Alamo will soon enter a new era with perhaps an even broader footprint.

The City of San Antonio and the Texas General Land Office, which operates The Alamo, formalized a partnership on October 9 to redevelop Alamo Plaza. The state committed $31 million for the project, with the city chipping in another $17 million. A fundraising campaign by the Alamo Endowment Board aims to raise hundreds of millions more from private donors.

The new plan could give the site a drastic makeover, reimagining its operations and design. Developing the plan will take at least a year.

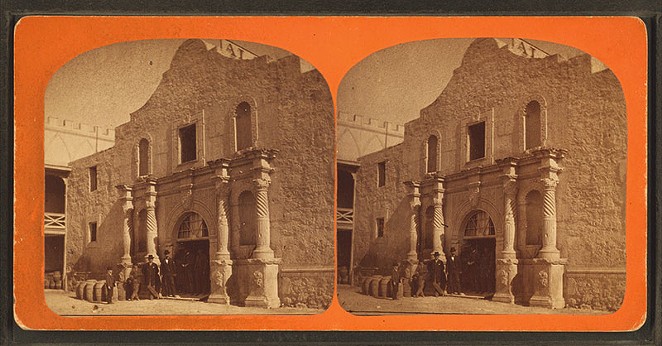

Although the Alamo's preservation is now meticulously planned, this wasn't always true. In the decades following the 13-day siege of 1836, the symbol of Texan independence crumbled and rotted.

Poop from swallows and bats, thousands of which colonized the rafters, piled up. Soldiers carved their names into walls and bored out old musket balls.

Souvenir seekers collecting chunks of rubble was not only common, it was practically legal. Through 1840, the San Antonio town council allowed people to fill up a wagonload of brick from the Alamo wreckage for $5.

While those who died in battle were honored, the structures they defended languished. The Catholic Church, which owned the Alamo at the time, sold the convento — where most of the fighting had occurred — in 1877 to Honoré Grenet, a French businessman.

Grenet used the remaining structure of the convento to build a grocery wholesaler. The business was an eyesore. Tourists and residents complained of commercializing the Alamo.

"It's a strange, very strange mingling of fame and sourkraut [sic], and still stranger the fact that the great State of Texas ... should permit a historic building like the Alamo ... to become a grocery warehouse," a tourist wrote to a Galveston newspaper in 1881.

The grocer changed hands in 1882. The new proprietors nearly sold the property to a hotel before it was acquired by the DRT, whose efforts helped restore the Alamo to its present state (though not without considerable internal strife).

Though the DRT is credited with rebuilding the Alamo, the Land Office is now its custodian. And how the agency balances the same issues that plagued the Shrine in the past – commercialization, expansion and preservation, to name a few – remains to be seen.