When King William was down on its luck, Mike Casey saw an artists' paradise

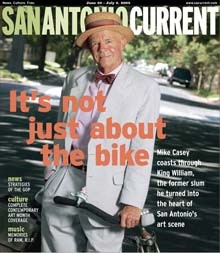

You may not know him, but you've seen him, weaving through downtown traffic on his Schwinn cruiser, wearing a seersucker suit with a straw boater perched on his silver-haired head. Mike Casey could be going to Blue Star Contemporary Art Center, where he is a board member, to the courthouse to meet a client in probate court, or to his King William home, where he has lived for more than 30 years.

"If you watch me ride, I'm coasting. I'm not in a hurry at all," says Casey, 64, whose bike, a replica, has one speed and coaster brakes. "It's energy-efficient in the summer. If you were to walk, you'd sweat. You are the breeze on the bicycle."

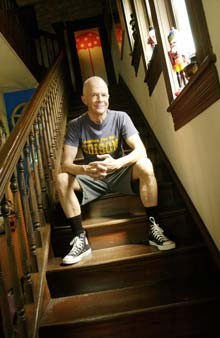

| Attorney and art patron Mike Casey in his King William home. (Photos by Mark Greenberg) |

Casey is not only the breeze, but also the honorary Mayor of King William, a title bestowed upon him by Bill Fitzgibbons, director of Blue Star Contemporary Arts Center. Although Casey has been a Blue Star boardmember almost since the organization's inception 20 years ago, he is probably best known as the landlord of The Compound, four duplexes and a single house on the corner of South St. Mary's and Stieren streets that many well-known local artists, including Chuck Ramirez, Anne Wallace, and Ethel Shipton, have called home. Since the 1970s, Casey's devotion to this neighborhood and the arts has transformed King William from a former slum to one of the most-coveted areas of the city æ and one renowned for its creative force.

"When Blue Star came along, it introduced people to King William who had never been to the neighborhood before," Casey says. "The urban living and the arts scene attract some people. And artists and architects are often the first to find an affordable spot with charm. They lead the way."

Casey has served on the Blue Star board for 20 years, but his affinity for art and design began in college, where one of his first roommates was an artist. "I realized they were different. They were so fascinating and their creativity so interesting," he explains. "I love the way artists and architects love detail."

Casey was born and raised in a working-class neighborhood between Hildebrand and Fresno west of I-10, and attended Edison High School, which elicits gasps from the upper crust who keep track of such things. When he graduated from law school at UT-Austin in 1966, more than 380,000 troops were fighting the Vietnam War. He was drafted, and the Army offered him the rank of captain and a job as a military lawyer if he signed up for five years. "I would have rather been shot at," Casey recalls. Instead, from 1967-1968 he served as an Army law clerk, including a posting in Long Binh, a U.S. military camp surrounded by barbed wire in the Vietnamese desert.

| Casey in seersucker suit and straw boater is a familiar sight to residents of Southtown. |

After completing his tour of duty, Casey returned to San Antonio. One day in 1972 he was driving on South Alamo Street when he noticed a "For Rent" sign on a two-story Victorian house, called on it, and found his home. "I opened the door and knew this is where I'm supposed to be."

Built in 1895, the ramshackle house was close to his work in the Tower Life Building and it was cheap, even by '70s standards: Casey rented the entire house for just $95 a month.

Although its bones were solid, the house was a wreck. The shower worked downstairs, but not upstairs. The sky peeked through a hole in the roof, which was visible from two floors below. Rain had rotted some of the floors. "When my friends saw it, they thought, Most people try to move up in life," he laughs.

In those days, the upwardly mobile did not move to King William. The opulent homes of today were then divided into as many as 14 apartments each, with hastily built add-ons to cram as many tenants as possible into each building.

Yet Casey and a few forward thinkers, including attorney Walter Mathis who restored more than a dozen homes, loved King William and all its eccentricities: Three go-go dancers and their children lived next door. Architect O'Neill Ford had an office on King William Street. And property owners, who are likely kicking themselves today, were trying to unload houses.

Casey began fixing up his rental home, and when the landlord and his wife visited one day to pick up the rent, they began to see the hints of splendor that lay beneath the plywood and rain-rotted floorboards. So they evicted Casey, thinking they would move in.

Casey relocated to a smaller, finished house behind his original rental. His landlord was a charro, a Mexican cowboy, who thought having a lawyer on his association board would be swell. So Casey became an honorary charro. He still has the card.

Eventually, he bought that rental from his cowboy landlord, then reclaimed his original rental house, purchasing it on a 30-year mortgage for $67 a month. "It was luck."

Casey's foray into the art world was equally inauspicious. In 1986, the San Antonio Museum of Art scheduled its first exhibition of local artists, but it was canceled due to lack of funding. The artists banded together and persuaded owners Bernard Lifshutz and Hap Veltman to let them use the empty commercial complex at 116 Blue Star. The group show drew 2,000 people. Encouraged by the turnout, the artists and their sponsors believed there was a viable art scene and planned more shows in the space. Today, that old vacant building is the Blue Star Contemporary Art Center, which is celebrating its 20th Contemporary Art Month as the anchor tenant in a complex of independent galleries and shops.

While contributing to the local arts scene, Casey has also been pivotal in keeping parts of King William affordable for artists. He purchased several other houses in the neighborhood and, as his renters moved out of the Compound, it was his policy to rent to artists and architects exclusively. Now he lets the current renters decide who will move in.

"The neighborhood used to have a lot of artists, but the rents have become so high," Casey says. "I've had artist friends looking for places and I don't want an adversarial relationship `with tenants`."

The Compound has become an unofficial artists' cooperative, with shared meals in the backyard and cheap rents. It is also the home of Sala Diaz art space, named after Alejandro Diaz, an artist now living in New York, who decided he would move into the back kitchen of his duplex and host shows in the front. When the space hosts openings, the couple who lives next door hosts a reception in their backyard garden.

"A lot of the work in my house is by my artist friends," Casey says. "Everything I have, I know the artist who did it. I'm surrounding myself with art that's fun to look at, and I'm trying to help out the artists in the Compound by buying their art."

Much has changed since the early years in King William, and because of Casey's unwillingness to charge exorbitant rents, the Compound is one of the few affordable places in the neighborhood. As Southtown becomes chic, its home prices have increased beyond the reach of the middle class, not to mention struggling artists. On choice streets such as Guenther, King William, or Madison, a 1,200-square-foot bungalow could cost you a quarter-of-a-million dollars.

"What are we going to become?" Casey asks. "A neighborhood of rich people?" The question is a good one. Recently, some King William residents have targeted First Friday because the social event-cum-art opening generates heavy foot traffic in the neighborhood. Casey says he understands why serious art patrons would like a less-crowded night of their own, but he also respects Friday's young audience as future art supporters.

Casey still lives in the house he bought in the 1970s; it is now 110 years old and does not have air conditioning. Occasionally, he'll hop the tourist trolley for lunch at Ácenar or Yokonyu ("I qualify for reduced fare. A round trip is 27 cents.") or, if he must drive, he hops in either his 1966 Mustang or his 1955 Rambler station wagon, the same car in which he learned to drive.

But most often you'll see him on his bike en route to his law office, which is also in a turn-of-the-century home, two doors from his house. His mother lives on King William Street; his friends live all around him.

"On First Friday I love going down to Blue Star, and I love sitting on my front porch and watching the parade of people go by," he says. "There's something going on and I'm in the middle of it." •

By Catherine Walworth and Lisa Sorg