In less than a year, SAWS’ CEO David Chardavoyne has retooled the utility’s mission: find and sell water — lots of it

CEO David Chardavoyne works in a building where oil once reigned, but is now occupied by water. The San Antonio Water System recently relocated its headquarters from East Market Street to the former Valero Energy building on Highway 281 North; Chardavoyne’s office, whose wooden doorways, chic lighting, and high ceilings lend it a sumptuous air reserved for the very powerful, belonged to Valero CEO Bill Greehey.

It’s debatable which is more valuable, oil or water. And as the former CEO of Thames Water Holdings, the U.S. subsidiary of the third-largest private water company in the world, Chardavoyne recognizes that water is the new oil, a sought-after commodity not only necessary for living, but that can generate a lot of money for those who own it.

| SAWS’ CEO David Chardavoyne (Photo by Mark Greenberg) |

Yet, Chardavoyne now leads a public utility, one subject to the vicissitudes not of shareholders, but of its board, City Council, and citizenry.

A youthful 57, Chardavoyne speaks in a formal, measured, yet friendly manner. His demeanor is a striking contrast to his predecessor, the stoic retired Air Force General Gene Habiger, a decorated war veteran and former commander of strategic nuclear forces, who, those familiar with the organization say, ran SAWS like a combat operation. The SAWS board terminated his contract in March 2004.

For the past five years, SAWS has come under fire from critics for a series of snafus: A 2000 external audit depicted a utility bloated by bureaucracy that could not adequately serve its customers. In 2001, $645,000 worth of computers was discovered missing. In 2002, a SAWS contractor mistakenly cross-connected recycled- and drinking-water lines leading to the River Road neighborhood, and residents said they subsequently became ill. And in a legendary team-building exercise at a 2003 management meeting, employees were required to eat raw eggs.

Such is the legacy that Chardavoyne inherited as he began his tenure at SAWS 11 months ago. Even his hiring stoked controversy: The SAWS board of trustees had passed over interim chief and former vice president of planning, Leonard Young, an African American, and hired Chardavoyne, a Yankee from the private sector, to retool the utility’s vision.

Yet, within months, Chardavoyne won over many SAWS detractors by scrapping two controversial water-supply projects, streamlining SAWS’ organization by hiring several new vice-presidents and eliminating 119 unfilled positions. As a result, Chardavoyne averted a projected 17 percent rate hike, reducing it to a more palatable 4.8 percent. As in the private sector, he aggressively courted new customers and, in doing so, locked horns with Bexar Met, another local water system.

Questions linger about the role of SAWS as a water wholesaler and Chardavoyne’s private-sector background, which is mixed and not without controversy. Yet, except for peeved Bexar Met officials, he has quieted many of SAWS’ most outspoken critics.

“I voted for him for Man of the Year,” says water activist Joe Pagliara, who has spent much of his retirement pounding out angry letters to SAWS — many of them containing the word “boondoggle” — on his 1942 L.C. Smith typewriter. “The new outfit in there is going to be good for San Antonio.”

Larry Hoffmann, a former member of SAWS’ Citizens Advisory Panel and frequent critic of some of the utility’s proposed projects, praises Chardavoyne. “I’m very pleased so far,” says Hoffman, who also applied for the CEO position. “He’s the best one I’ve seen, period.”

One of Chardavoyne’s priorities was to examine and update the city’s 1998 water-resource plan. As with many parched areas in the U.S., San Antonio’s population continues to increase; state demographer projections estimate that between 1.6 and 2 million people will live in Bexar County by 2040. Since SAWS can’t rely solely on the Edwards Aquifer for water, Chardavoyne’s continuing challenge is to ensure Bexar County will have enough water for the next half-century.

This summer, as part of the 2005 water-resource plan update, Chardavoyne, with the board’s approval, axed the Simsboro Project, known as Alcoa, and the controversial $971 million Lower Guadalupe Supply Project, much to the delight of environmentalists and to the chagrin of the Guadalupe Blanco River Authority, SAWS’ “partner” in the project.

“The word ‘partner’ may not be appropriate,” Chardavoyne says, adding that SAWS would have been contractually responsible for 89 percent of the costs, while the GBRA would have been responsible for 1 percent, and the San Antonio River Authority, 10 percent. SARA could have shifted its costs to SAWS, bringing the utility’s financial burden to 99 percent.

Under the GBRA, SAWS would have pumped water more than 100 miles uphill from the Lower Guadalupe River near Victoria. Not only was it expensive — with much of the cost passed on to ratepayers — but SAWS wouldn’t have had full water rights. The environmental impacts on bays, estuaries, and endangered whooping cranes could have been devastating.

“Even if we needed the water, it wasn’t a good plan,” Chardavoyne says.

The Lower Colorado River Authority Project (see box, this page) remains on the table as a possible water source, as do other initiatives:

• A $58 million desalinization plant to treat brackish water in south Bexar County could provide as much as 10,000 acre-feet a year. An acre-foot is about 328,000 gallons. Cost per acre-foot: $565.

• At a cost of $93 million, recharge dams would capture water over the Recharge Zone, allowing it to seep into the aquifer. Cost per acre-foot: $469.

• By purchasing additional water rights in the Edwards Aquifer, SAWS could tap into 60,000 acre-feet a year. Capital costs are estimated at $47 million. Cost per acre-foot: $181.

• Although some rural residents oppose the $540 million Regional Carrizo Project, it would pump groundwater from Wilson and Gonzalez counties via a 60-mile, 54-inch pipeline to SAWS’ Twin Oaks Treatment Plant. Cost per acre-foot: $851.

An aquifer storage and recovery system in south Bexar County allows SAWS to store water during rainy periods and withdraw it during dry stretches. The utility will continue to campaign for recycled water — the new Toyota plant will use up to 80 percent recycled water for its industrial processing — and conservation, initiatives supported by local environmental groups such as the Sierra Club, Smart Growth San Antonio, and Aquifer Guardians in Urban Areas.

San Antonio lowered its water use from more than 200 gallons per person per day in the 1990s to about 125 gallons today, ranking among the lowest usage in the U.S. Chardavoyne predicts that during a “normal” year, San Antonians could use as little as 116 gallons per person per day.

| Chardavoyne won over many SAWS detractors by scrapping two controversial water-supply projects, streamlining SAWS’ organization and averting a projected 17 percent rate hike, reducing it to a more palatable 4.8 percent. |

Although San Antonians’ water austerity cost SAWS $2 million in revenues last year, Chardavoyne isn’t asking residents to use more water to offset the loss. “You can never exhaust conservation efforts.”

Ten minutes before a public meeting at Harlandale High School, Chardavoyne is eating a chocolate chip cookie to fuel him through the next hour. The SAWS board approved a proposed 4.8 percent rate hike on October 18, and Chardavoyne is in the midst of four public meetings scheduled over the next week to sell ratepayers on his vision for San Antonio. The previous evening, about 25 people showed up for a public meeting on the North Side; tonight, there are just three.

Despite the low turnout, Chardavoyne and CFO and vice president of financial services, Doug Evanson, unveil SAWS’ five-year financial forecast. Last year, SAWS projected 17 percent rate hikes through 2007, and 8 and 7 percent increases in 2008 and 2009, respectively. Chardavoyne has sharply reduced the 2006 increase, and estimates the hikes will range from 7 to 9 percent through 2010.

Translated into dollars, in 2006, a typical household will pay an extra $1.93 each month, totaling $40.96, still less than Fort Worth, Houston, Austin, and Corpus Christi.

Moreover, Chardavoyne says, SAWS will have access to 2.4 percent more water than had been allotted in the 1998 plan.

City Council will vote on the 2006 rate November 17.

In the presentation, there are also hints of previous administrations’ inefficiencies: Projects that were budgeted in 2000 never made it to the board for approval, and thus, never started. Consultants, who were hired to study the most mundane of issues, now must be approved by Chardavoyne and the board. “We have a lot fewer consultants now,” Evanson says.

By the end of the meeting, a South Side neighborhood leader who says she was skeptical initially, is sold on Chardavoyne: “I was impressed.”

Bexar Met is booing. The applause for Chardavoyne’s bold, even surgical, decisions, a skill he honed in the private sector, has been tempered by a turf war between SAWS and Bexar Met, a water company that supplies areas throughout Bexar County.

At stake is a current and potential customer base worth millions of dollars. Bexar Met has filed suit against SAWS over service to a 5,000-acre community in north Bexar County. Bexar Met alleges SAWS is violating an agreement to allow Bexar Met to serve the area; Chardavoyne contends the document in question wasn’t approved by either utility’s board and isn’t legally binding. Moreover, he says, developer Gene Powell requested SAWS service for the area.

Yet, the dust-up indicates a recasting of SAWS’ role in the region: Once a mere water retailer, SAWS now sees itself as a wholesaler, which means it needs more water to sell to other systems and communities.

“The crux of the issue is that they’ve taken the position that they’re superior to everybody else, that they should get to take over whatever they want, whenever,” says Lesley Wenger, part of the new guard on the Bexar Met board. “Everybody is pretty ticked off at SAWS.”

Chardavoyne says that the SAWS board’s directive is for SAWS to become a regional water wholesaler and that the utility is well-equipped to fulfill that mission. “Financially, technically, and in human resources, we are the largest organization and we have a role as a regional provider,” he says. “It’s unfortunate that Bexar Met has that view. We recently agreed to temporarily supply water to a 480-unit development in Bexar Met territory that they couldn’t service.”

Trinity University anthropology professor John Donahue, who criticizes what he calls SAWS’ “project culture” in the book Globalization, Health, and Water, sees SAWS as a positive regional force. “I think it’s a good idea; they’re certainly the major player in the area. The only danger is that smaller purveyors see this as a takeover.”

SAWS does appear to be capitalizing on Bexar Met’s recent string of misfortunes, including the firing of general manager Tom Moreno. An audit showed Bexar Met overspent its budget by 24 percent last year and overpaid its lobbyists. This summer, Bexar Met had to buy 65 million gallons of water from SAWS to meet its customer needs in Stone Oak, not because Bexar Met didn’t have water, Wenger says, but it had nowhere to store it. The utility is addressing the storage issue, Wenger says.

Chris Brown, treasurer of Smart Growth San Antonio, says the new Bexar Met board offers an opportunity for the two utilities to cooperate. “That’s if SAWS and Bexar Met acted as partners instead of one-upping each other. I hope SAWS would recognize that even gorillas live in society. Beating up your next-door neighbor is not the common way to succeed in a social group.”

Pummeling your opponent can be a successful strategy in the corporate world, where Chardavoyne spent more than 20 years of his professional career. In addition to his stint at Thames, he was president and COO of Jamaica Water Supply Company, the largest investor-owned water utility in New York state. Chardavoyne also held high-level positions at another private utility, United Water Works, and when he became an independent consultant for Detroit’s troubled Public Lighting Department, the Michigan Citizen referred to him as a “privatization wiz,” raising fears among employees that the utility would go private. It didn’t.

Chardavoyne says SAWS employees occasionally have asked him about privatization, but he has assured them that SAWS won’t be privatized. “It’s a robust organization; it wouldn’t make sense. If a public operation is dysfunctional, one way to turn it around is privatization.”

Jamaica, New York residents would likely disagree. In 1992 — before Chardavoyne was hired at Jamaica Water later that year — the state utilities commission issued a report critical of the company; it ordered Jamaica Water to refund $30 million and cut rates to its customers after state audits found overcharges as a result of inefficient management. The commission later settled with Jamaica to refund $11.7 million and freeze rate increases for four years.

In 1993, Newsday quoted Chardavoyne as saying there was no basis for the refunds and rate cut recommended by the commission, calling the allegations “unsubstantiated.” The commission later reviewed Jamaica’s operations and according to commission documents, “found that nearly every function had inefficiencies and problems.”

Chardavoyne says he was hired as a troubleshooter to revamp Jamaica Water after its chairman discovered problems while preparing to take the company public. He was not responsible for the prior mismanagement.

“The commission came down strongly on the company,” Chardavoyne recalls, “but we worked with the commission. We agreed changes were needed, but the commission agreed it overreached.”

A Public Citizen report critical of water privatization, Water For All, lists dozens of environmental violations by Thames UK, which managed its U.S. subsidiary, Thames Water Holdings, for whom Chardavoyne worked as CEO from 1999 to 2004. However, Chardavoyne wasn’t involved in Thames’ operations in Britain or other countries outside the U.S.

(Thames, which owns systems in Africa, Indonesia, Europe, South America, and Canada, was later purchased by the German company RWE.)

While SAWS itself won’t be privatized, Chardavoyne says, the utility plans to bid on a private contract to supply water to Fort Sam Houston. “The Department of Defense has decided it’s not in the water business; it `SAWS’ service` makes a lot of sense.”

In his first year, Chardavoyne has cut fat, ditched projects, and professionalized SAWS’ institutional culture. Yet, his toughest challenges lie ahead: Shedding SAWS’ image of a water bully as he develops the utility into a regional supplier, addressing water-quality issues — activists such as Aquifer Guardians in Urban Areas’ Annalisa Peace have long complained about SAWS’ alleged lackadaisical aquifer division — and keeping rates low while mending miles of ancient pipes.

The era of eating raw eggs is gone; what remains to be seen is how far Chardavoyne’s private-sector experience can take him in the public world — with City Council, his board, and San Antonians watching. •

By Lisa Sorg

|

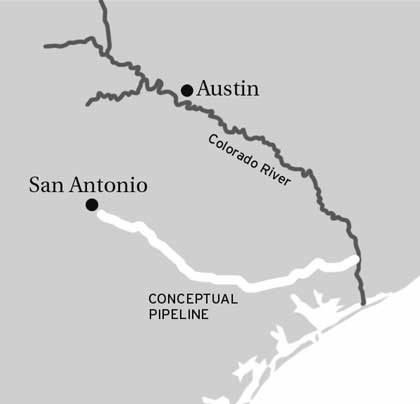

An acre-foot is equal to about 328,000 gallons. An acre-foot of LCRA water would cost $980, the most expensive project SAWS is considering as part of its 50-year water-supply plan. The project is in the second year of a $42 million, seven-year study to determine the project’s environmental and economic feasibility. In its partnership with the Lower Colorado River Authority, SAWS is paying the majority of the study costs, which initially were estimated at only $7 million. If the project is approved, SAWS would use surface water from the Colorado River and groundwater from the Gulf Coast aquifer, which would be pumped through 165 miles of pipeline from Bay City uphill to San Antonio. SAWS would enter into a 50-year contract with the LCRA, with a 30-year renewal option. Critics of the project emphasize that SAWS, even after pouring in more than a billion dollars, still won’t own the entire pipeline or other infrastructure. Water activist Joe Pagliara calls the project “the worst deal ever proposed in SAWS’ history,” because San Antonians will bear the brunt of the costs. Pagliara estimates a typical SAWS customer would pay more than $1,000 through 2050 to pay for water development, most of if for the LCRA project. SAWS CEO David Chardavoyne acknowledged that the utility will own a portion, but not all, of the pipeline, but says LCRA “has indicated an openness to renegotiate” the 74-page contract. Chardavoyne says federal funding is also available for the project. Former Citizens Advisory Panel member Larry Hoffmann questions whether SAWS could access the full 150,000 acre-feet, particularly during a drought. Although Austin discharges 100,000 acre-feet of treated wastewater into the Colorado River each year, the City could decide to use that supply to support new development in the fast-growing area, thus cutting into the amount available for SAWS. “If this were our only water source, then we’d be up against the wall,” Hoffman says. “But it’s not. I doubt the LCRA will fly; it’s too expensive.” • |