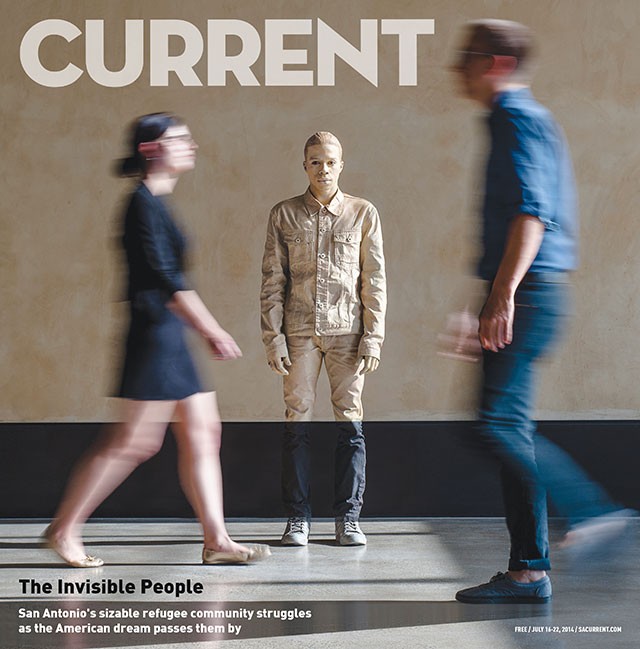

The refugee camps are packed with tents, bamboo huts and nationless people.

There is no electricity to speak of and women, men and children wait in lines 100-deep for hours two times daily just to get drinking water, said Sita Regmi, a refugee from Nepal who has been in the U.S. a little more than three years now.

Regmi lived in a refugee camp along the Nepali border for five years with her husband, Parsuram, who was expelled from his native Bhutan in the early 1990s and spent 18 years in a camp. They met in Regmi’s hometown of Phidim, Nepal, where Parsuram worked when not confined to the refugee camp. Both were eventually resettled in San Antonio and now have jobs in the health care industry—Regmi at a home health care agency and her husband at an area hospital.

“Can you imagine how long without electricity?” Regmi asks. “Eighteen years [for my husband.]

“I lived with my family, and he [Parsuram] found a job over there [in Phidim]. After we married, I came to camp.”

Regmi’s story is proof that love knows no borders, but neither do injustice and tragedy.

At one point, a couple decades ago, more than 100,000 Bhutanese—most of Nepali descent and known as the Lhostshampa—were herded into the refugee camps set up along the southeastern border of Nepal, which also shares a border with India. They had been forced out of their homes in southern Bhutan, victims of a government crackdown that basically stripped them of their human rights and declared them “illegal immigrants” based on their ethnicity—even though most Lhostshampas traced their roots in Bhutan back to the 19th century or earlier, when they were encouraged to settle there to farm the land.

Those who protested the Bhutanese government’s increasing repression, which escalated starting in the mid-1980s, were persecuted, many tortured. By the early 1990s, thousands found their citizenship revoked, their homes leveled and the majority of their community forced to flee en masse to squalid border camps set up in Nepal to handle the exodus. The United Nations finally intervened in the late 2000s, and since then has helped to resettle some 80,000 Bhutan refugees in other countries—with more than 66,000 accepted by the United States alone. Nearly 800 have been resettled in San Antonio to date, State Department figures show.

The story of the Bhutanese refugees, unfortunately, is not unique. The U.N. estimates that as of 2012 there were more than 15 million refugees worldwide—which, in terms of scale, is nearly twice the number of people who live in New York City.

Since the mid-1970s, the United States has resettled in excess of 3 million refugees, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], which, along with the State Department, oversees and funds refugee resettlement programs in this country. Up to 70,000 refugees will be resettled in the U.S. in fiscal year 2014, which ends September 30, President Obama’s Proposed Refugee Admissions report to Congress indicates.

In fact, since 2004, nearly 5,200 refugees from 28 nations have been resettled in the Alamo City, according to Department of State data, including more than 1,200 from Burma, nearly 1,100 from Iraq and 1,221 from 13 African nations. No precise figures are available on the current size of San Antonio’s refugee community because the information is not tracked systematically, given the refugees “are on a path to U.S. citizenship,” Lisa Raffonelli, a spokesperson for HHS’ Office of Refugee Resettlement, said.

In general, the Current discovered there is a lack of centralized data on the nation’s refugee community. Federal, state and local agencies all track the information separately and often use differing methodologies, so it’s nearly impossible to compare San Antonio’s refugee-population track record with the performance of other cities.

As a result, local experts can only estimate the size of the Alamo City’s current refugee community—putting the number at about 10,000 to 12,000, and growing. That takes into account children born to refugee families after they are resettled here and also those who have come to San Antonio outside the State Department-sponsored resettlement process—such as those who become eligible for refugee status under U.S. law once they cross the border, even on their own accord.

In addition, other factors on the global level could expand the refugee population further in years to come. For example, the thousands of unaccompanied children crossing the U.S. border in recent months—most fleeing violence and poverty in Central America — are not currently considered refugees and remain subject to deportation. But that policy could be adjusted in the future due to international pressure, allowing more of them to remain in the United States.

That growth poses both opportunities and challenges for the City of San Antonio. The opportunities exist in the cultural texture and depth the refugee population brings to a city already well known for its tourism and diversity. The challenges, however, are daunting, and are reflected in the harsh economic realities confronting this population.

The Race to Self-Sufficiency

Employment data tracked down by the Current paint a grim picture for refugees resettled in San Antonio, who, under existing law, are given a short period—essentially 180 days—to make the transition to self-sufficiency after they land in the United States.

“Nobody can become culturally acclimated in six months. It’s impossible,” said Margaret Costantino, founder and executive director of the Center for Refugee Services, a small nonprofit that provides services to the city’s refugee population.

The big player in the city on that front, though, is Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of San Antonio Inc. It is the lead government contractor locally charged with assisting the 700-plus refugees resettled in the city each year by the Department of State, in coordination with HHS. The goal of Catholic Charities’ Refugee Services department is to ensure the individuals it assists attain self-sufficiency within four to six months of being picked up at the San Antonio airport—again, an objective mandated by federal programs funding those efforts.

The services provided to refugees by Catholic Charities include assisting “with housing, food and clothing, employment, language, translation, general adjustments and acculturation,” according to the organization’s 2012 annual report—the latest available online.

Public records show that in fiscal 2014, Catholic Charities in San Antonio received nearly $1.5 million in federal funding—some passed through the state of Texas—to provide services to refugees resettled in the Alamo City. The money includes a $110,440 Refugee School Impact grant, $432,042 in Refugee Social Services funding and a $946,000 federal matching grant, according to the Texas Health and Human Services Commission [HHSC].

Catholic Charities is also required, as a condition of some of the government funding, to match a portion of the federal money it receives with its own cash or in-kind contributions.

Paula Walker, refugee services director for Catholic Charities in San Antonio, said the nonprofit also has a $112,000 contract through the state of Texas to provide health screening services to refugees within the first 30 days of their arrival in the city.

In addition, the Department of State provides Catholic Charities with a $1,925 lump sum per refugee to assist them with meeting expenses during their first three months in the United States. That stipend—$800 of which is for Catholic Charities’ administrative expenses, like staffing and office space—helps the refugees pay for rent, clothing, food and other basic necessities.

Walker said programs like the federal matching grant cover those basic needs for another three months after the initial stipend is exhausted. But after six months, the cash assistance times out—though employment, language and other social services are made available to the refugees for up to five years.

Walker said the refugee population in San Antonio has many needs, and resources are always stretched. But she also stressed that she believes refugees “have a great shot” at having a much better life once in the United States, “especially knowing where they came from, their plight.”

“The number of refugees that come to the U.S. is a very low number compared to the displaced persons in the world,” she said. “Many get turned away. … [Those that make it here,] they’re the survivors.”

But even if the refugees arriving in San Antonio can be considered better off from a global perspective simply because they are no longer living in tents in refugee camps or dodging bullets in war zones, it is clear that a large number of them, by any reasonable U.S. standards, appear to be falling through the cracks on the road to self-sufficiency.

The employment rate among the 720 San Antonio refugees who participated in state of Texas-sponsored job-services programs in fiscal year 2013 stood at only 57 percent for that year, Texas HHSC data shows. That means 43 percent of the individuals tracked did not find jobs. The good news, according to HHSC spokesperson Linda Edwards Gockel, is that 344, or 84 percent, of those who did find work in fiscal 2013 retained their jobs for 90 days or more—considered a strong retention rate.

However, the average wage for the 411 refugees who did find work in the Alamo City in fiscal 2013, according to HHSC data, was a scant $8.46 per hour (compared with a statewide average of $8.93 for refugees). In addition, among those who did find work, only 337 landed jobs that offered health benefits.

The federal Office of Refugee Resettlement, part of HHS, also provided the Current with an analysis of local refugees covered under the federally funded “matching grant” program in fiscal 2013.

Most refugees in Texas are enrolled in the program, HHS’ Raffonelli said, and are provided employment services through it for a maximum of 180 days. At that six-month cut-off in fiscal 2013, HHS figures show, only 77 percent of the 587 San Antonio individuals participating in the matching grant program were deemed “self-sufficient.”

Now, in fed-speak, self-sufficient simply means that at least one person in the family unit had a job and no one in the family was receiving any direct cash assistance from the government—though participation in Medicaid, food stamps or another non-cash programs is allowed in the calculation.

The disturbing revelation in the HHS analysis is that even with those government-funded benefits included, some 23 percent of the 587 individuals at day 180 still failed to meet the self-sufficiency test.

Walker points out that the employment statistics alone don’t tell the whole story, since refugees “may not get employed immediately [or at least within the six-month window that guides federal program funding] due to a number of obstacles.” For example, she said there has been a surge in Cuban refugees arriving in San Antonio this year, 127 since February.

Many are arriving outside the State Department-resettlement process. Under federal law, Cubans making it to U.S. soil, such as entering the country on their own from Mexico, can automatically be granted refugee status and become eligible for employment and other social services. However, Walker noted that for Cuban refugees, it takes more than four months to obtain necessary employment authorization cards, potentially skewing employment data conclusions.

In addition, she said shorter-term employment outcomes for refugees are affected by the lack of affordable child-care options available to refugee families. Consequently, one spouse may have to remain out of the workforce longer until a workable child-care solution is found.

Walker stressed that when viewed over a longer timeframe, past a year, the employment statistics for refugees improve considerably. Though she did not provide specific data, Walker claimed the job-placement rate for the employable refugee population served by her organization was around 69 percent for 16 months between October 1, 2012 and January 31, 2014.

But even if the 69 percent figure Walker provided is accurate, it still means 31 percent of the refugees, even after being in the country up to 16 months, still remained unemployed in a city where the overall unemployment rate hovers around 5 to 6 percent.

“We all, as resettlement agencies, feel that refugees do need more time [and funding to become self-sufficient]—easily one year,” Walker said. “But will the American people like that?”

Culture Shock

St. Francis Episcopal Church and a number of other local faith communities across multiple denominations have long recognized that the needs of the refugee community outstrip existing resources and, consequently, have been very active in reaching out to bridge the gaps.

St. Francis, for example, hosts a free refugee health clinic twice a month that is run by students and faculty from the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. It also sponsors food and clothing drives, hosts English as a Second Language (ESL) classes, provides land for a community garden and was the site for the annual World Refugee Day celebration held in late June.

Rev. Cristopher Robinson, rector of St. Francis, located on the Northwest Side (in the heart of San Antonio’s refugee community), said his first experience working with refugees was actually in Austin, while he was in seminary school.

“I worked getting jobs and apartments for these refugees as they were coming in and saw the [rough] conditions in which these folks had to live on the East and South sides of Austin,” Rev. Robinson said. “And I was the one who asked the question: ‘Why are we bringing people to the states and setting them up for failure?’

“We are putting them in amongst urban poor who are not the same culture that these folks are,” he added. “They don’t speak the same language, they [the refugees] don’t have the support system.

“And the answer I got,” Rev. Robinson recalled, “was, ‘Alive and poor in Austin is better than dead in the Sudan.’ I guess there’s some merit to that but at the same time, what we’re able to do is not enough.”

The refugee resettlement program is premised on the philosophy that refugees “should be encouraged and motivated to become self-sufficient as quickly as possible,” explained Daniel Langenkamp, spokesman for the U.S. State Department. If they are not self-sufficient, he added, then the goal is to mainstream them into programs that assist other low-income Americans, such as Medicaid or food stamps.

“Mainstreaming is important: There needs to be a lot of motivation and encouragement for people to become self-sufficient,” Langenkamp said.

Unfortunately, it appears that many refugees are not even taking advantage of the dwindling social safety-net programs that are available to all “low-income Americans.” Often, Costantino and others said, it’s because they simply don’t understand how the U.S. bureaucracy works nor do they have the language skills or civics knowledge to complete lengthy forms (especially if they are online), schedule appointments or navigate the city’s transit system in order to get to appointments.

“Most of the people doesn’t know, if those papers come from Health and Human Services, they don’t know what to do,” said Nepali refugee Regmi, who added that she and her husband volunteer a lot of time assisting fellow refugees in filling out paperwork or checking newspaper want-ads for them because many can’t read English.

“And most of the time, they [other refugees] lose the food stamp or Medicaid, but why? [Because] they doesn’t know when it need to be renewed,” Regmi added. “They still eligible for Medicaid, but didn’t know how to renew the Medicaid or how to renew the food stamp.”

Dr. Robert Ambrosino is a professor in the University of Texas—San Antonio Department of Social Work who has researched the refugee community and made it the focus of past graduate-level studies for his students. He points out that the expectations being placed on newly arrived refugees are extraordinary, given very few of us would succeed in becoming self-sufficient within six months after being transplanted from the United States with no savings and dropped in a foreign land where we don’t know the culture or language.

Many of the refugees being resettled in the United States, Ambrosino claimed, have to endure great “stressors” in their lives due to the over-crowded conditions in the refugee camps and the horrific events they have witnessed in conflict zones. These stressors negatively affect both their physical and mental health, and are amplified by the culture and financial shock experienced once they arrive in the United States.

“For example, they [the refugees] all have to sign a promissory note with the U.S. government promising to pay back the money spent to fly them to the United States,” Ambrosino said. “In the case of one father I met, who had a family of 10, he was facing a $15,000 promissory note that he had to pay back, and that was from day one in this country.”

Langenkamp confirmed that the refugees are required to repay the cost of their plane tickets and have up to five years to do so interest-free. He added that failure to repay the note could affect an individual’s credit rating but also said it’s “relatively easy to get an extension” on the repayment terms.

Resources Stretched

The Center for Refugee Services, an all-volunteer grassroots group that punches way above its weight class, also seeks to address the economic and social-services needs of the refugee community.

The nonprofit offers a range of economic, community and social services from its small office at 8703 Wurzbach Road on the Northwest Side—including English classes, employment assistance, a food pantry, transportation assistance, and health and wellness support. It also plans to open a small craft shop onsite, as well as a community garden.

CRS’ most recently available Form 990 tax filing, shows the nonprofit took in about $35,000 in revenue in 2012, with nearly $13,000 eaten up by rent. CRS’ Costantino concedes the group operates on a shoestring, but she credits the volunteer spirit of its members for having an impact far beyond the meager dollars the organization has at its disposal.

“Yeah, we’re doing it with nothing, keeping our utilities and our rent paid,” she said. “Volunteers have passion and resources and can accomplish the most amazing things just because they want to help people.”

Costantino is hopeful by nature and believes the children of the refugees are key to lifting their families out of poverty, if access to education is assured. But she also sees danger signs ahead if the cycle of poverty is not broken.

“As this [refugee] population grows, and if problems are not addressed, it will become a big problem for the city …” she said.

The bulk of the refugee families resettled in San Antonio are placed in apartments that too often are in rough shape and located in hardscrabble neighborhoods—such as the Gardendale/Wurzbach Road area near Interstate 10 on the Northwest Side, Costantino points out. That area is served by Northside Independent School District, which, in the 2013-2014 school year, NISD officials confirmed, enrolled a total of 1,069 refugee students.

Noelia Benson, director of bilingual and ESL education for NISD, explains that in addition to providing English-as-a-Second-Language services to refugee students, the school district also “utilizes newcomer schools, where newly arrived immigrant students are provided the opportunity to acclimate to school life in smaller class-size classroom.” According to Benson, NISD offers support in as many native languages as the district can find tutors. They also provide summer enrichment activities and integrated studies so students can consistently practice speaking, listening, reading and writing skills.

NISD Principal Rebecca Barron-Flores, in an article penned for the National Association of Elementary School Principals, also makes clear that language acquisition isn’t the only hurdle some refugee children must overcome—particularly those from impoverished developing countries.

“For example, we have had to teach many of them how to use a restroom properly, and how to go make choices for the lunch meal and eat in the cafeteria,” Barron-Flores wrote. “Initially, many of them would urinate on the playground and—rather than using the tables and chairs in the cafeteria—they would sit on the floor … and eat off one another’s plates.”

But, regardless of the need, there is no free lunch when it comes to providing the enhanced services necessary to assure these refugee children are at least given a chance to succeed after starting out so far behind in the race to self-sufficiency.

“NISD currently spends about $1.8 million [annually] on staffing for refugee students,” Monica Faulkenberry, NISD’s assistant director of communications, said. “This is above and beyond the regular education staffing.”

Educating a Community

Buddha Nepal is a senior at UTSA who expects to graduate with a degree in mathematics this December. He holds down a job at a local fast-food restaurant, working his way through college and living in an apartment complex that he says challenges his safety daily. But Nepal has faced adversity in his life before and understands what it means to be a survivor.

“I basically lived 15 or 16 years in refugee camp,” Nepal said. “I was three months old at most when I lived in Bhutan and moved to [a refugee camp on the border of] Nepal.”

In the summer of 2008, shortly after being resettled with his family in San Antonio, Nepal and half a dozen or so other young refugees, with the assistance of some mentors and legal research, essentially organized a sit-in outside the registrar’s office at NISD’s O’Connor High School. The group refused to leave until they were assured that the young refugees gathered there that day (ages 18 to 21) would be admitted to high school. Until that point, Nepal said refugee students 18 and older (including his sister and uncle, but not Nepal who was 17 at the time), were not being allowed into NISD high schools due to their age.

Nepal’s tenacity paid off and the refugee students who assembled at O’Connor that day were enrolled in NISD high schools. “Everyone thought I was [a] troublemaker,” Nepal recalled. “[But] I wasn’t going to go anywhere. I wanted answers.

“… My parents told me, ‘Why you doing this? You don’t need [to] get involved in this,’” Nepal added. “I said, well, ‘No. I’m not going to give up. It’s the right thing to do.’”

Nepal’s act of nonviolent civil disobedience at O’Connor High School in the summer of 2008 appears to have played a key role in shifting NISD policy on admitting refugee students who are ages 18 or older. Today, NISD officials confirmed, students up to the age of 22 are admitted to high schools in the district.

“The statements you make and attribute to Buddha Nepal are accurate,” NISD Executive Director of Communications Pascual Gonzalez said. “When student Nepal’s plight became known to us, it was apparent that we were facing a new phenomenon in NISD.

“… We needed to put systems in place that would allow our older refugee students to be successful,” Gonzalez added. “By this time, NISD had become the district of choice for refugee students of all ages (with and without proof of age), from a variety of countries and language backgrounds, and with none to some previous education.”

Nepal’s leadership and organizing skills are an example of how the refugee community itself has the power to find and pursue solutions to some of the issues they face.

But other problems are so intractable and complex that solutions seem certain to remain elusive absent a far broader coordinated approach involving a coalition of players citywide.

“The main issue I see, is the jobs,” Nepal said. “Because they [refugees] have no education [and limited or no English], they are working hard-labor jobs, so education is very important.

“[But] the students [refugee children] lose interest in education … or they have to go to work,” Nepal added. “Family members have to contribute to rent and utilities and other stuff, and they usually have no benefits, and most do not know how to apply for Medicaid and food stamps. And if they do apply, usually they are turned down.”

Consequently, he added, many refugees end up getting locked into low-paying, backbreaking, benefit-less, dead-end jobs at an early age. And because Texas did not expand Medicaid under the federal Affordable Care Act (Obamacare), most refugees—like working poor with minimum-wage jobs— fall into a salary band in which they aren’t eligible for health-care subsidies nor do they qualify for Medicaid.

The statistics from NISD are not promising either. For the 2012-2013 school year, 38 refugee students graduated from high school, while 11 dropped out—a 77.5 percent graduation rate. By comparison, NISD’s overall graduation rate for 2013 was 92.4 percent.

The two figures aren’t comparable apples-to-apples, given the former is an annual average and the latter based on a four-year running average, but clearly the graduation-data snapshot for the NISD refugee students isn’t entirely positive.

Even with Nepal’s victory in getting NISD to raise the age cap on students admitted to high school, Costantino of CRS said some students continue to “age out,” because if they start high school as freshmen at age 19 or older, they have three years or less to finish a four-year program before turning 22.

Costantino said CRS has a program in place with a local private school to help some of those students graduate with a high-school diploma, but more resources are needed.

Gonzalez said many of the refugees arriving in San Antonio from “all points all over the world” have no educational records, formal schooling or even birth records. So, he said, “when in doubt,” the older children are placed as freshmen in high school, and “some could well be 19-years-old.” He stressed that NISD does all it can to make up the deficits—which can be “massive” and can include a lack of basic arithmetic and English literacy.

“Catholic Charities provides them with six months [of economic] support. Obviously that is not enough for many of these families,” Gonzalez added. “Most of the refugees who leave NISD high schools leave because they have to go to work to support their families. While GEDs are an option, even these are quite challenging for them.

“Aging-out may be a contributor to the drop-out issue among refugees. But the main reason is economic. Until this is addressed, the problem will continue.”

Overcoming Inertia

Though the issues plaguing San Antonio’s refugee community may be legion, and in many cases inseparable from the woes affecting the city’s low-income population in general, for any positive change to take hold, the first steps must be taken, local experts argue.

Roseann Vivanco, a Health Science Center clinical instructor and nursing director for the San Antonio Refugee Health Clinic, stressed that “there needs to be better coordination and trust among the people already working hard to meet the needs of this population.”

In fact, the Refugee Health Clinic is a model for that cooperation because it brings together health-care students and faculty from three different disciplines—nursing, medicine and dentistry—to provide free care to refugee families in a culturally friendly setting twice a month (with plans to expand to once weekly), via assistance from St. Francis Episcopal Church, which hosts the clinic. The free clinic is funded by the Center for Medical Humanities & Ethics at the Health Science Center.

Vivanco said the clinic’s staff had 153 patient encounters in 2013 and, as of June 3 of this year, that number was at 72 and rising. Those patients are getting access to affordable health care early, in their neighborhood and through a collaborative model that benefits both the refugees and the Health Science Center students, Vivanco stressed.

With the right space and funding mix, some argue, that model could be expanded to encompass other services for the refugee community.

Dr. Andrew Muck, also a Health Science Center clinical instructor and the Refugee Health Clinic’s medical director, explained that creating a care environment that is culturally sensitive and easy to access for refugees is key to catching problems early, before they become life threatening and treatment gets more expensive. Muck noted one case he encountered recently in which a refugee delayed seeing a doctor due to cost concerns, resulting in a simple urinary track infection becoming a systemic one that required hospitalization and ended with a $48,000 bill.

“One of the things I think about with health care issues specifically, what you learn from a clinic like this, is with culturally sensitive and language-specific care, you can do a lot fairly inexpensively, with some forethought, with some motivated, caring individuals, which San Antonio is known for,” Muck said.

Over the past year, councilman Ron Nirenberg, who represents the Northwest Side’s District 8, where many of the refugees live, has been convening what he calls “refugee summit” meetings at City Hall with key stakeholders that serve the refugee community in San Antonio—such as NISD, VIA Metropolitan Transit and Catholic Charities, among others.

“The idea was to get all of these service providers communicating and hopefully collaborating,” Nirenberg said. “What I’ve asked city staff to do, which they have done, is to assemble a matrix of services that are out there for refugees.

“I don’t really know what our end game is in terms of our role as the City, but what I think it is [is] that we help create some kind of collaborating organization that helps keep all these pieces moving in concert, and the resources coming in and working in concert, and making sure we have real trackable outcomes that are positive for the families and their communities.”

Nirenberg concedes that “funds are stretched at every corner of the state and country,” but he says he is optimistic that “there’s a lot of efficiency and efficacy to be found just by coordinating, and we should start there.”

One thing is clear in Buddha Nepal’s mind, however. San Antonio’s refugee population is growing, “and it will keep growing,” he said. With a potential surge of people applying for refugee status due to sectarian violence in the Middle East and gang brutality in Central America, the time to act is now.

“I think the school district and San Antonio as a city need to look at the situation,” he added. “Most refugee parents right now are just working and do not have an education.

“But their kids do know the system, more than their parents, and if they go bad, a whole generation could go bad, and it will be too late after that. They need some direction … to encourage them to do the right things.”