The San Antonio Art Institute may be fading from public memory, but its legacy shines on in the Southwest School of Art's effort to become the first independent fine arts college in Texas, and the internationally acclaimed resident artists' program at Artpace. While some memories are bitter, the SAAI served as the city's primary incubator for contemporary art for more than 50 years.

The SAAI fostered modernism by hiring many respected artists to teach its programs from the late 1920s to the 1980s, until a doomed attempt to establish a bachelor of fine arts degree combined with a faltering Texas economy led to bankruptcy in 1993.

In "School at Sunset Hills: San Antonio Art Institute Artists in the McNay Collection," on view through February 15 at the McNay Art Museum, curator Jackie Edwards examines a golden era from 1943 to 1953, when the school was housed in an aviary beside Marion Koogler McNay's mansion, known as Sunset Hills.

Mrs. McNay, through her contacts with the pioneering Los Angeles art dealer Dalzell Hatfield, invited many cutting-edge West Coast artists associated with LA's Chouinard School of Art to teach at the SAAI. Before her death in 1950, Mrs. McNay assembled one of the best collections of modern French painting west of New York. But she also avidly collected American contemporary art, and the McNay opened in 1954 in her mansion as the first private modern art museum in Texas.

Edwards says the McNay has from 80 to 100 works in its permanent collection by artists associated with the SAAI, but the cozy "Sunset Hills" exhibit focuses on fewer than 10. Many more years may pass before passions about the closing of the school will cool enough to allow the McNay to present a more comprehensive exhibit about all the artists who taught at the SAAI.

Beginning in 1927, the Witte Museum offered free weekly art classes. Famed muralist Xavier Gonzalez was the first instructor, and Harding Black taught ceramics in the Ruiz House. The public school system supported the classes until 1933, and then the state provided partial funding. In 1939, the San Antonio Art League raised funds, and classes were taught in the former Brackenridge Park studio of Mount Rushmore sculptor John Gutzon Borglum.

World War II caused classes to be suspended in 1942. Witte director Ellen Quillin persuaded Mrs. McNay to house the school on the grounds of her 23-acre estate. Mrs. McNay wanted the art school to be modeled on the Chicago Art Institute, which she attended, and requested that it be named the San Antonio Art Institute. The SAAI re-opened in a converted aviary on October 15, 1943, under the joint sponsorship of Mrs. McNay and the Art League.

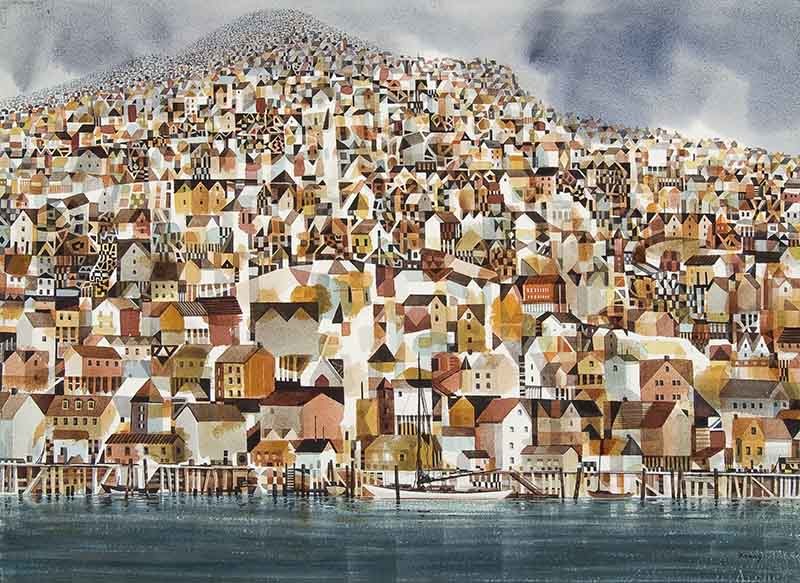

"School at Sunset Hills" provides an overview of important artists Mrs. McNay invited to teach at the SAAI. Destined to become one of Texas' best-known artists, Michael Frary, who taught at Chouinard, moved to San Antonio in 1949 to be artist-in-residence and faculty chairman. His watercolor of a Mediterranean village reflects the imaginative complexity he later applied to his meticulous paintings of woods, rock formations and rivers. But Frary's fame came after he moved to Austin to teach at the University of Texas.

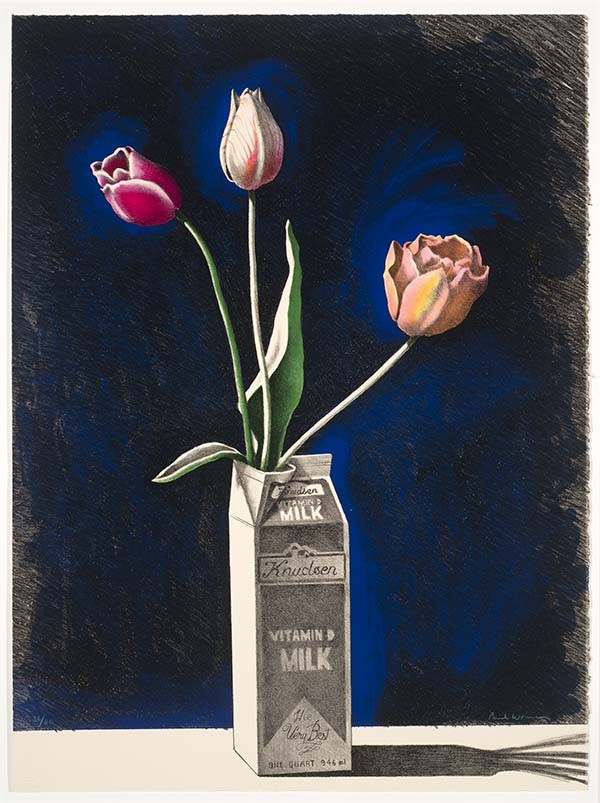

Painted in a thick impasto of green, yellow and black, Dan Lutz's expressionistic Ojai Oak (1947) is the most impressive work by a Los Angeles artist who taught at the SAAI. But the best-known California artist is probably Paul Wonner. He was one of several artists in the military stationed in San Antonio during World War II that Mrs. McNay allowed to use the art institute's studio. Wonner is renowned for his oddly surreal still lifes, such as Tulips in a Milk Carton (1983).

Dean Fausett painted his two Hill Country landscapes while he was working on murals at Randolph Air Force Base. Dallas artist Dan Wingren, represented by the melancholic Man Strolling (1961), already had achieved national notoriety as a "young artist to watch" when he became director of the SAAI in the 1950s.

From Mrs. McNay's original bequest is a painting of a Girl in Blue (1932) by Cecilia Steinfeldt, who became known as the "First Lady of Texas Art" for her work as a longtime curator at the Witte.

In her will, Mrs. McNay stipulated her desire to turn her home into a museum and to use the grounds for the school whose purpose would be "to teach creative modern art." But the museum's board was given the final authority over the use of the property.

The Art League continued to oversee the school until 1962, when the SAAI incorporated. Alden H. Waitt, a retired major general, served as director and chairman for 16 years and led the school to independent status. Retired Episcopal Bishop Everett H. Jones and his wife, Helen, paid for the construction of an 11,000-square-foot building that opened for classes in January of 1976. The Jones Building, all that remains of the SAAI, now houses the McNay's administrative offices.

By 1980, when the board passed a resolution that the SAAI should become a college of art, the school served about 500 community students annually. In 1982, McNay trustees designated 4.5 acres for the SAAI, which decided to hire a world-class architect "to make a statement."

After approaching architects such as Philip Johnson, Robert Venturi and Michael Graves, the board hired Charles Moore of Moore Ruble Yudell. He designed a more than 40,000-square-foot facility modeled on a Mediterranean village compatible with the Spanish Mediterranean buildings of the McNay estate.

In 1983, the institute's board of trustees launched a $7.5 million fundraising campaign. But the economic recession of the late 1980s made it difficult for the SAAI to collect all its pledges. The SAAI decided to build the new facility in stages, but was unable to complete construction because of cost overruns (the budget ballooned from $3.2 million to $5 million) and under-funded pledges. The building ultimately proved too impractical and expensive.

However, the SAAI faced its first major crisis when George Parrino, the president who persuaded the board to establish a fine arts college, left in 1984 to become head of the Kansas City Art Institute. His successor, Robert L. Cardinale, from Boston University, stayed for only five years and was replaced in June of 1990 by Russell Cargo, who had been serving as dean.

By September of 1991, the SAAI had 60 employees, including 23 staff and 37 faculty. It reported a $1.6 million operating budget and a $2.2 million endowment. There were 1,597 students enrolled, including 600 children, 452 adult non-credit students and 89 BFA students. Since 1988, the SAAI had graduated 10 students with BFA degrees.

But in the end, as Linda Pace, the last SAAI board chairwoman, noted in a memo to the trustees, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS) turned down the Institute's application for accreditation because of "the demonstrated lack of financial stability; and the demonstrated lack of continuity of leadership. In a real sense, money is at the root of both reasons."

Initial projections for enrollment in the BFA program proved to be highly overestimated, while the costs of installing the crucial infrastructure to support a degree program—an academic dean, registrar, admissions officers—were underestimated.

The SAAI struggled to continue as a community school. However, the SAAI board faced a series of lawsuits filed by students, staff and donors. Shutting down the BFA program made it difficult to raise new money. Finally, the SAAI board decided to cease operations and file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in May of 1993.

Twenty-four former students each received $2,400 in a $55,200 settlement. Some of the faculty tried to keep the school going. But according to the institute's agreement with the McNay, if the SAAI was dissolved, all the buildings, facilities and endowment reverted to the McNay, which closed the school for good in August of 1993.

Pace used the SAAI's visiting artists program as a model for Artpace, which opened in January of 1995. Among the visiting artists brought to San Antonio by the SAAI were Deborah Butterfield, Peter Dean, Luis Jimenez, Ken Little, Melissa Miller, Frank Stella, James Surls, Rufino Tamayo and James Turrell.

Paula Owen became president of what is now the Southwest School of Art two years after the SAAI closed, but the Institute's failure provided valuable lessons in what not to do as she oversees the establishment of a new BFA program. Unlike the SAAI, the Southwest School already has good facilities and a stable faculty and administration, not to mention significant earned income in addition to tuition, grants and donations.

"Everything we're doing is geared toward getting accredited," Owen says.

Currently, a $1.3 million, 3,000-square-foot addition is being constructed for the ceramics studio. To celebrate its 50th anniversary next year, the Southwest School expects to successfully complete a $10 million capital campaign with $2.5 million earmarked for scholarships and the rest to be used to purchase a city block (directly across Navarro Street from the campus) for future development.

On the McNay grounds, the Moore building stood vacant for 10 years and, despite a great deal of community criticism, was demolished by the museum in 2003 to make room for the Jane and Arthur Stieren Center for Exhibitions, which opened in the summer of 2008.

School at Sunset Hills: San Antonio Art Institute Artists in the McNay Collection, $15-$20, 10am-4pm Wed, 10am-9pm Thu, 10am-4pm Fri, 10am-5pm Sat, noon-7pm Sun, 10am-4pm Tue, McNay Art Museum, 6000 N New Braunfels, (210) 824-5368, mcnayart.org, through Feb 15