Prior to the April 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, a persuasive case could be made that the most horrific act of terrorism ever committed on U.S. soil was the 1963 Birmingham, Alabama, church bombing that killed four young African-American girls.

The bitter racial climate in Alabama at the time made it almost impossible to bring the perpetrators to justice, but more than three decades after the tragedy, key conspirators Thomas Blanton and Bobby Frank Cherry were finally indicted and convicted for their participation in the crime.

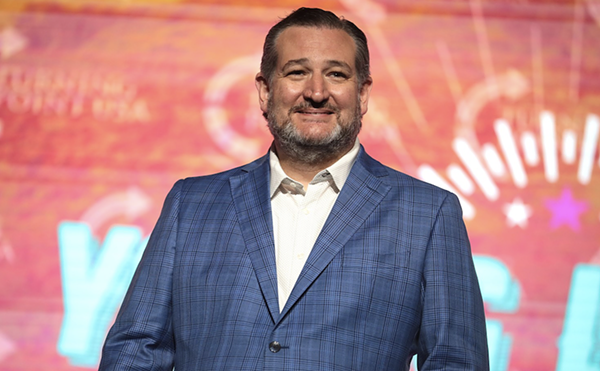

Doug Jones was the prosecuting attorney who handled the Blanton case. Jones, 54, has a unique perspective on the case and the Deep South’s racial evolution. An Alabama native, he was in grade school when the bombing occurred, and 38 years later, his work helped his home state begin the process of healing an old wound.

On Saturday, September 20 (only five days after the 45th anniversary of the church bombing), Jones will speak in San Antonio as part of the Know Why You’re Marching Civil Rights and Film Series. He talked to the Current about the case’s lasting impact.

You were 9 years old when the bombing happened. What memories do you have from that time?

I wish there was some romantic answer that I could give about how I remember all of this. But the fact is, I lived on the outskirts of Birmingham in a suburb. It was a typical, segregated-type community. It was segregated schools and segregated churches. In those days, without interstates and media and all, I was a 9-year-old white kid in a different world. I don’t recall that much about this. My mind was just somewhere else. It really was not until later, in high school and college, when I got to learning more about Birmingham and the movement, and getting to meet some of the people that were involved, that the issue really began to take hold for me.

Did the adults around you talk about it at all?

I don’t remember adults talking about the bombing itself. I remember just the general talk about the Civil Rights movement and Dr. King and the things that were going on in Birmingham, and the fact that they had to call out the National Guard in Selma.

See, it was not until the later ’60s, when I started junior-high school, that the issue came into focus for me, because that was the first time that I went to a school that had black children there as well.

My parents were conservative, but they were not the kind of people that would engage their children in discussions about those kinds of events. To some extent, I wish they had, but then there’s a part of me that is glad that I got shielded from some of that as a kid, because it allowed me to form my own opinions as I grew.

What were the biggest challenges you faced in prosecuting the case so many years after the fact?

Time and everything that goes with it. By that, I mean witnesses who were dying; witnesses whose memories were fading; trying to reconstruct evidence in a way that a modern jury would focus on.

From that passage of time, everything else flowed. There were pieces of evidence from the bomb scene that we couldn’t find. Fortunately, all the interviews were there. But when you’re talking to people who haven’t been interviewed about this case for 40 years, it’s hard to get them to recall.

The interesting thing about it is that while time was the biggest challenge, it was probably also the thing that helped us the most. It allowed Birmingham and the community to change so dramatically that the government could get a fair trial with this evidence. We didn’t go into court knowing that we had a jury composed of white men that would likely rule against us.

In the early ’60s, Alabama was widely perceived as the ultimate symbol of racial discrimination. How have you seen it change since then?

I think there has been a dramatic change in Alabama, particularly in Birmingham. That is not to say that we are the epitome of the dream that Dr. King talked about in 1963, because we’re not. But I don’t think that any state is, whether they’re from the South, the North, the East, or the West.

But Birmingham has had a black mayor since the late 1970s. Birmingham has celebrated its past, instead of running away from it. There’s a Civil Rights Institute that recognizes and memorializes the contributions that Birmingham and Alabama made to the Civil Rights movement. Kelly Ingram Park and the church itself have been renovated. Birmingham has learned to live with the mistakes, but also learned from the mistakes. I think we’re still growing.

For so many years, people still tended to think of Birmingham in images of black and white, but I believe that the convictions of Blanton and Cherry, some 37, 38 years after the horrendous act that they did, has really opened the eyes of the country to the fact that Birmingham is a community of living color these days. We’re not perfect, but we’ve come a long, long way. •

LECTURE

Know Why You’re Marching: Doug Jones

Noon Sat, Sep 20

Free

Martin Luther King Academy

3501 Martin Luther King Dr.

(210) 226-9041