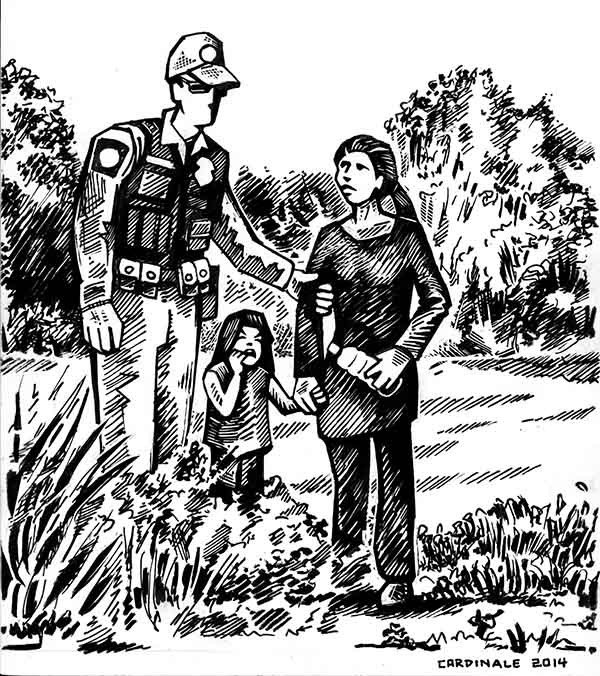

Fearing for her son's life and her own, Maria* fled the most violent country in the world to seek refuge with family in the United States.

In Maria's home country of Honduras, gang violence and homicides permeate daily life. According to the United Nations, Honduras had the world's highest murder rate in 2012: 90.4 murders per 100,000 people. Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala are among the top 10 countries with the highest rates of gender-based killings, according to the Geneva Declaration on Armed Violence and Development, and rape and domestic abuse are rampant. Decades of political strife and drug-related crimes have led to turmoil in Central America, and women and children often find themselves targets, unprotected by local governments and law enforcement.

During the past year, the world watched in horror as an unprecedented number of unaccompanied children and minors, mostly from Central America, appeared at our southwestern border, fleeing gang violence and abject poverty in their home countries. Simultaneously, more than 68,000 families, mostly Central American mothers with young children also escaping gang-related threats or domestic or sexual violence, were apprehended at the border between October 2013 and September 2014.

In response to what President Barack Obama called an "urgent humanitarian crisis," the administration quickly and unapologetically re-instituted a policy that has already failed once: detaining women and their children who have suffered from violence in for-profit jail-like centers—even after they've been found to have credible claims for asylum and pose no security or flight risk. The administration's goal? To deter other refugees from making the trip.

But while the federal government argues it is acting in the name of national security, it's doing so at the expense of vulnerable women and children who have suffered great trauma, abuse and psychological damage, all of which have been found to be exacerbated by detention. On top of that, the families are caught up in a complicated, impersonal legal process that seems to be designed to keep them locked up.

Detention Policy Expands Overnight

Prior to this summer, Immigration and Customs Enforcement screened and temporarily held migrant families at a smaller-scale 96-bed detention center in Leesport, Pennsylvania.

Almost overnight, two larger facilities popped up near the southwest border this summer: a 700-bed center in the remote town of Artesia, New Mexico, and another in our own backyard, one hour southeast of San Antonio. The 532-bed Karnes County Residential Center is a former adult-male civil detention facility that was converted this August to house migrant women and children. Plans are underway for an even more massive family detention center in Dilley, Texas, an hour southwest of here.

The news sent shockwaves through the human rights, refugee, advocacy and legal communities, which remember fighting the deplorable conditions women and children were living in at the T. Don Hutto Residential Center, north of Austin, just five years ago. For months, they have been sounding the alarm about the inherent problems of locking up women and children, and arguing against the arbitrary incarceration of vulnerable asylum-seekers.

"Warehousing women and children is wrong on several levels: it inhibits due process, it is harmful for the women and the children. It separates families and it's depriving people of their liberties unnecessarily," said Adriana Piñon, of the American Civil Liberties Union in Texas. Piñon has visited with families detained in South Texas. "These children and women have left their home countries where they've suffered a range of terrible realities and they've endured horrific travails en route to the United States, and once they get here, we deprive them of their liberty."

Been There, Done That. And Failed

In 2009, the Obama administration acknowledged the ills of family detention and ultimately decided to stop jailing women and children at the T. Don Hutto facility. Advocates and immigration lawyers spent years fighting to end the practice there, unearthing cases of sexual abuse, maltreatment, malnourishment of children and other inhumane practices. Just five years later, federal officials have reversed course and returned to family detention in full force.

Barbara Hines, a lawyer and professor at the University of Texas Law School and Immigration Clinic, helped lead the years-long effort to end family detention at Hutto. Now, in her pro-bono work with families detained at Karnes, she said she is seeing some of the same instances of abuse and maltreatment play out in these newer facilities.

"I was shocked," Hines said. "I couldn't believe that after the Obama administration had realized that family detention was wrong and had taken the steps five years ago to really end family detention as a policy ... that [it] took the most extreme and radical position that it could have with regard to mothers and children."

As feared, allegations of sexual abuse at Karnes are already surfacing. In early October, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund (MALDEF) and the UT Immigration Law Clinic filed a complaint alleging sexual assault and abuse at the facility. According to the complaint, women allege they are being lured from their rooms by guards and personnel for sex. The complaint also alleges that guards and staff are requesting sexual favors from detained women in exchange for money or help with their immigration and asylum cases. Women also report being kissed or fondled by guards in front of other detainees, including children. Lawyers say these alleged instances and the authorities' failure to address them violate the Prison Rape Elimination Act, passed by Congress in 2003.

"Guards using their respective positions of power to abuse vulnerable, traumatized women all over again is not only despicable, it's against the law," Marisa Bono, a staff attorney with MALDEF, said when the complaint was initially filed.

A second complaint was filed highlighting inadequate access to medical care, mental-health treatment, legal counsel and other resources. Hines and other attorneys who provide pro-bono representation to detained women and children say mothers are reporting that their children are losing weight and are showing signs of depression and emotional distress. Other mothers report that they are separated from their children. In one case, a mother whose baby was just learning to walk reported that she wasn't allowed to put her child on the floor and was instead forced to carry the baby, Hines said. Another mother reported to her lawyer that she wasn't able to heat up milk after 7 p.m. to feed her baby.

"You cannot humanely detain families," Hines said. "There isn't a model that works to lock up children."

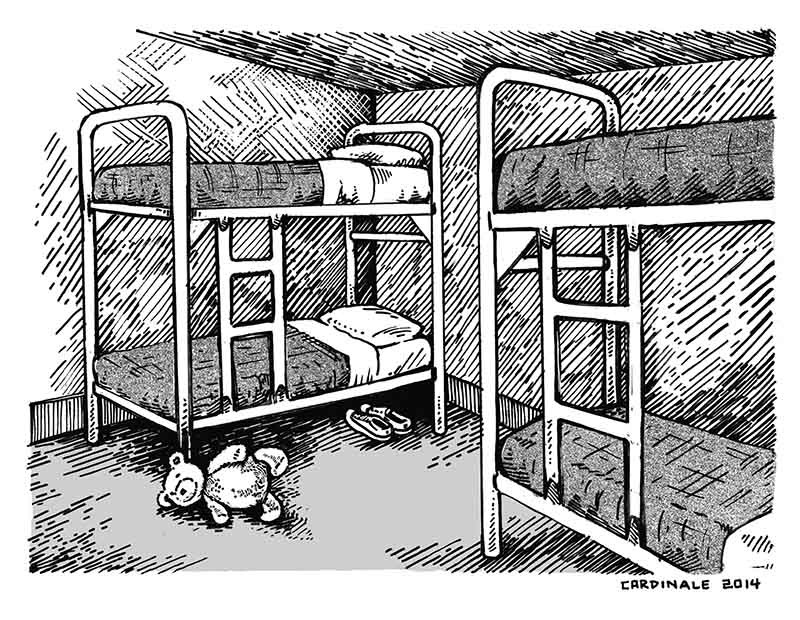

Human rights advocates acknowledge that the conditions they've observed at the Karnes facility are somewhat better than those at Artesia and at T. Don Hutto. For example, rooms house eight people total, with four bunk beds, a bathroom and a vanity table. A courtyard and volleyball and basketball courts are available for families, as well as classrooms for children. Piñon, who visited Karnes with other advocates, reports that women and children aren't forced to wear uniforms like they were at Hutto and do have some free movement throughout the facility during certain hours of the day.

Still, there's no pretty way to dress up family detention. No amount of courtyards or sports areas can make incarcerating abused and traumatized women and children OK nor do recreational facilities eliminate the possibility of abuse or harassment at the centers.

"ICE has made changes from [Hutto] to Karnes, but that doesn't change the underlying concerns we have with family detention," Piñon said. "Locking people up and depriving them of their liberty has serious implications."

Inadequate medical and mental-health resources is another cause of concern. While a medical facility is open onsite at Karnes, a number of advocates and lawyers interviewed for this story, as well as instances detailed in a new report by the Women's Refugee Commission and Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services, say that their clients aren't receiving the care or medication that they've requested. Counseling is also available, but advocates worry women and children who have experienced domestic or sexual assault are not getting the degree of treatment that they need.

"I think what we know about domestic violence and sexual assault is women are already suffering from a sense of a lack of control in their life and privacy, and trying to reestablish a trust with society. In the detention centers, that type of trauma that they've suffered comes back in sometimes very vicious ways," said Anne Chandler, the Houston director of the Tahirih Justice Center, who organizes pro-bono legal counsel for families detained at Karnes.

Seeking Help, Immediately Detained

Maria, who worked at a clothing factory in Honduras, was threatened by the infamous Mara Salvatrucha gang after her son's father, whom she is no longer married to, became a target. When gang members couldn't find her ex-husband, they tracked down her and her then 8-year-old son. One day, as she was coming home, two men in masks approached the taxi she was riding in. The men warned that if she didn't turn over her son, they would find a way to kill him and her as well.

Before this summer's family detention policy was expanded, women and children who passed both an initial border-patrol interview and the so-called "credible-fear interview"—successfully demonstrating to an asylum officer that they have reason to fear returning home—were often able to remain with relatives, family friends or in other non-detention settings while their asylum cases worked their way through immigration court.

Now, advocates and lawyers report that the screening process is too hasty, producing flimsy results and putting women and children who suffered great trauma in confusing and impersonal situations—especially those who don't speak English. Evidence suggests that families aren't properly referred for a credible-fear interview until after they are detained, according to lawyers and the Women's Refugee Commission and Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services organization.

Such was the case with Maria, who arrived at the border with her son on July 31. Her initial border-patrol interview included no real details about her reasons for fleeing to the United States. She was given a notice of removal, and she and her son were ultimately detained at Karnes on August 8. It wasn't until weeks later that an asylum officer conducted a more in-depth interview and determined that she and her son had a credible fear of torture back in Honduras.

Most women incarcerated at Karnes are like Maria and asylum officers believe they have strong asylum claims. Data outlined in the Women's Refugee Commission and the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service report show 98 percent of families detained at Karnes would likely qualify for asylum. As of July, more than half of the families detained in Artesia had expressed fear of returning to their home countries. The report also explains that 1,050 children detained at the three operating facilities are under the age of 18 and more than half of them are 6 or younger.

In addition to expanding detention, the federal government seems to be making it as hard as possible for women and their children to be released while their cases work their way through court.

Jonathan Ryan, executive director of the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services (RAICES), has been representing women and children detained at the Karnes facility since early August. In each case for which he and other RAICES attorneys have filed bond requests, the federal government's lawyers have filed a 50-page packet of documents arguing that allowing the release of families with pending asylum claims will only motivate others to come to the U.S.

Nina Pruneda, San Antonio-based spokesperson for ICE, said bond decisions are made on a case-by-case basis, "based on considerations of risk of flight and public safety."

In the last few weeks, Ryan and other lawyers have successfully secured lower bond amounts for some clients detained at Karnes, including a $3,000 bond for Maria. "The crux of our argument is that, one, these women are not threats to the community or to our country; and two, that they will appear in court," he said.

Some 10 weeks after they were detained at Karnes, Maria and her son were reunited with her uncle in Maryland. Now, about one month later, the federal government has filed paperwork to appeal their bond. In addition to the bond appeals, Ryan has also noticed that bond requests are more heavily scrutinized with each week that passes.

"It's all part of an attempt to prevent these women's stories from being heard, to keep their faces from being seen," he said.

Hope from the Highest Immigration Court

While the Obama administration has made the expansion of family detention centers a priority, the Board of Immigration Appeals issued a landmark ruling 20 years in the making that could have a profound effect on some of the migrant women detained by ICE.

In late August, the BIA recognized domestic violence as a valid asylum claim, giving women who have suffered abuse at the hand of their intimate partners a better chance at seeking protection in the United States. Women fleeing violent partners are now recognized as members of a "particular social group," one of the five grounds for asylum. The decision resolved a decades-old case involving a woman from Guatemala who applied for asylum after being abused by her partner.

"What the decision means is that it puts women who have suffered domestic violence on solid legal ground for asylum," said Lisa Frydman, of the University of California-Hastings Law School's Center for Gender and Refugee Studies.

While the government doesn't keep data on the specific types of asylum claims moving through lower immigration courts, Frydman said that 300 domestic-violence asylum cases were pending in the BIA before it reached its August decision. For the women detained at Artesia and Karnes, the ruling will have an impact.

"We have heard that a significant percentage of the women, the mothers, at Karnes and Artesia have fled situations of domestic violence," Frydman said.

The Center for Gender and Refugee Studies has been working with lawyers representing women in Artesia and, according to Frydman, all six domestic-violence-based asylum cases have been granted.

Denise Gilman, co-director of UT's Immigration Clinic, has been coordinating a network of pro-bono lawyers to help women detained at Karnes. She said about 30 to 40 percent of the cases she's seen likely involve domestic or partner-based violence, including at least two of the eight cases taken up by the clinic.

"It's hard to pin down numbers because, unfortunately, one of the problems with Karnes is that we're not able to reach women and children detained there for representation," she said. "In our broader network of pro-bono attorneys who have been trying to provide representation to women and children, there are definitely a number of additional domestic-violence cases that involve horrific abuse by partners against the women who are seeking asylum and detained at Karnes."

While it's hard to know how many detained women have domestic-violence-based asylum cases, the ruling did help the first family gain asylum and leave Karnes in late October, which wouldn't have been possible without the BIA decision. According to the family's lawyer, RAICES attorney John Blatz, the mother of two was brutally beaten, raped and sexually abused at the age of 14 by a man who eventually became her husband, and she lived in fear with him for 20 years. He left the country for almost a decade, and when he returned, he threatened her again, so she fled.

"It was pretty awful domestic violence," he said. Her asylum case "would've been long and drawn out because they had not ruled on it...once [the BIA decision] came out, it was much more of a possibility."

Blatz told the Current that the mother and her two children have been released from Karnes and have reunited with family in Atlanta.

The Community Responds

As lawyers on the ground in Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona and other states are stepping in to represent detained women and children, international and national advocacy groups and some lawmakers are calling for a major policy change. Dozens of groups are urging the Obama administration to rely on "alternatives to detention," including community support programs, release on parole or bond or periodic check-ins with a detention officer.

Other organizations are prepared to pursue litigation should the situation escalate and allegations of abuse continue. The ACLU, the American Immigration Council and other immigration lawyers have already sued the Department of Homeland Security for the release of the policies and procedures used to operate the Artesia facility, which advocates say was opened too hastily. Back at Karnes, Hines says the Office of the Inspector General is investigating the sexual-assault allegations detailed in the October complaint.

RAICES, which has offices in San Antonio and Austin, has started an online fundraising campaign in partnership with the UT Immigration Law Clinic and local law firm Akin & Gump to help families make their bond payments. So far, the fund has paid for the release of three families. The organizations hope to raise a total of $150,000 by the end of the year. RAICES is also working with San Antonio families who have volunteered to open their homes to migrant families released on bond through what they've dubbed the "Welcome Home" program.

As lawyers and advocates fight for families in court and through grassroots outreach, there's a bigger question that can't go unmentioned.

"Using moms and children for a supposed deterrent policy is wrong; women are going to come anyway," Hines said. "They're coming because they're looking for a safe haven. We need to start looking at why people come and what's really going on in Central America."

*(At her request, and at the request of her attorney, Maria's real name has been changed. Her asylum application was shared with the Current with her permission.)