Nationally, Texas ranks among the lowest in funding for mental-retardation services. What does that mean for the future of state schools and community programs?

| Editor’s Note: This is the second in a two-part series about the social and fiscal dilemmas of caring for people with mental retardation. In Part One, parents, advocates, and caregivers discussed their arguments for and against closing state schools, an issue that has been widely debated in mental-retardation circles and the Texas legislature. Families talked about their children and siblings Amy, Rix, Steve, Scott, and Barbara and their experiences in state schools, group homes, and foster care. To protect the privacy of the people and their caregivers, last names have been omitted. To read Part One, follow this link: “A great divide.” |

Thanks to the judicial system, mentally retarded Texans are back to strike two.

In the debate among parents, advocates, and policymakers over whether to close state schools for the mentally retarded in favor of community-based services, as is the national trend, the conversation inevitably turns to money. Here is something everyone can agree on: Texas doesn’t adequately fund mental-retardation services. An inequitable tax system, misguided legislative priorities, and bureaucratic inefficiencies contribute to a human-services system that cannot keep pace with the demand.

According to the Texas Department of Aging and Disability Services, the legislature appropriated $783 million through 2007 for the 11 state schools, plus Mexia State School, which includes specialized wings for adults and children with severe behavioral problems and those who have been committed by the courts, and the Rio Grande State Center, which cares for the mentally retarded and mentally ill. Yet that is not enough money to upgrade outdated computer equipment, significantly boost staff wages, or eliminate extensive waiting lists for community services.

| Although Cory can’t use his upper body, the SASS staff adapted a jig board at the Developmental Center so he can work with his feet putting sprinkler connectors in bags. He can’t speak, so to help him communicate he has an electronic talking board on his wheelchair and his home and workplace have pictures on the walls. By pointing to the pictures with his foot, he “says” many phrases, including “I want to go outside,” “My name is Cory,” and “I love you.” (Photos by Mark Greenberg) |

To save money, in 2003 the legislature considered closing or consolidating state schools. “It was feasible,” says Jennifer Harris of the state’s Health and Human Services Commission. “Is it advisable? It was a bit cautionary.” In March, a consultant’s report found that, because of the outstanding bonds on state-school properties, the state wouldn’t be in the black for at least 10 years. Moreover, the report concluded, the stress of closures on state-school residents and their families didn’t justify the savings. The fate of elderly and medically fragile people with mental retardation lies at the core of the argument for keeping state schools open. Even if siblings assume legal responsibility for their mentally retarded brothers and sisters after their parents die, parents still worry about how their children will be cared for.

“It’s our little secret that we hope our children die before we do,” says Elizabeth, a widow, whose daughter Amy is medically fragile and has lived at San Antonio State School for 27 years. Elizabeth’s daughter, Susan, will be responsible for Amy after their mother’s death. “Parents feel out of control. What will happen to my daughter when I’m gone? It’s valid and it needs to be said.”

Alta’s son, Rix, had lived at SASS since it opened in 1978. Although completely blind from retina disease and an accident, he still enjoyed his life at SASS, including attending church services with his mother. “He seemed very good-natured and accepting of it,” she says.

Last fall, Rix suddenly developed a blood clot that traveled from his leg to his lung. He died of a pulmonary embolism, as his father had in 1986. While Alta grieved the loss of her first son, she also felt relieved. “I’ve thought several times that I don’t have to worry about Rix anymore,” she says. “And I don’t think I have to apologize for that.”

Whether it’s spending on state schools or community services, Texas ranks among the bottom nationally in funding and services. According to David Braddock’s book, Disability at the Dawn of the 21st Century, the statistics for 2000 are embarrassing: 41st in spending on supported employment, 47th in funding for supported living and personal assistance, 40th in spending for community long-term-care services, and dead last of all states in number of community placements per 100,000 people. (See box, page 13.)

“There’s no doubt we rank low nationwide for mental-retardation services,” says State Representative Vicki Truitt, a Republican from Tarrant County. She sits on the House Appropriations Committee and the Public Health Committee, for which she serves as chairperson of budget and oversight. “There are a lot of competing interests.”

| Matt, shown here dancing at the San Antonio State School’s annual Fiesta celebration, has lived at the facility for more than 10 years. |

Truitt suggests Texas’ tax system is to blame for chronic underfunding of education and health care: too many sales-tax exemptions and too few businesses paying franchise taxes. “There are a whole lot of people paying no taxes,” she says, “and we’re not adequately accommodating the growth of Texas.”

The $783 million appropriation still falls short of what is necessary to care for the state’s most vulnerable citizens. For example, according to DADS documents, funding won’t pay for extra caseworkers to handle additional people needing long-term care in the community. In the past decade, the average number of clients per caseworker has increased from 169 to 445.

DADS has also been asked to increase residents’ monthly personal-needs allowances from $45 to $60. This alone will produce a $13 million shortfall.

And the Promoting Independence Initiative, a proposed pilot study to analyze the costs and benefits of moving 146 people from private and public institutions into home-based care, was cut by nearly $1 million. As a result, only 95 people will be in the study.

These larger budget woes are felt locally. Nearly two-thirds of the San Antonio State School’s budget comes from federal funds allocated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, including Medicaid, which is consistently at risk of being slashed. The rest of SASS’ budget comes from state revenues, which SASS officials say never cover the budget. This year’s funding shortfall was 4 percent of the $23 million operating budget; to make ends meet, SASS cut back on travel and office expenses and dipped into the workman’s compensation fund, which was running at a surplus.

|

Matt’s dream

The previous day he had returned from a week-long trip home to Cleveland, Texas, where he celebrated his 44th birthday by going fishing with his family. “We caught two ice chests full of fish,” he tells me, spreading his hands about a foot apart, like many fisherman do when they’re telling stories of their big catch. Matt lived at Abilene State School, a nursing facility, and several group homes before moving to San Antonio State School almost 11 years ago. He left the nursing home because of the expense, but enjoyed his life in group homes. In a workshop, he earned money packaging plastic silverware for airports and sorting nuts and bolts. At SASS, his life is full. He spends time with his friends and works at the Developmental Center assembling sprinkler components. He uses the money to buy gifts for his fiancée and a new rod and reel and tackle box for himself. FULL STORY |

During the last session, the legislature approved $241 million from the state’s general fund for a $100-per-month raise for unionized state-school employees. Yet many direct-care staff still earn less than $25,000 a year. And the benefits that attract workers to these state jobs have been reduced. New hires used to qualify immediately for health insurance a major selling point but now have to wait three months.

Low wages, delayed benefits, and the nature of the job residents with severe behavioral problems can spit, kick, or hit direct-care staff has resulted in a 47-percent turnover rate at SASS. “We spend a lot of time interviewing and training and mentoring them, and then they leave and we have to start all over,” says SASS Superintendent Ric Savage.

The starting hourly wage for some workers in private group homes is worse: $6.71. For those wages, by the time group homes ferret out criminals and those without a high-school diploma or GED, the employee pool is shallow. “There’s not been a cost-of-living raise in five years,” says Kitty Hernandez of R&K Specialty Homes. “And it takes a lot of work and staffing to teach them how to care for people.”

Yet, the most notable impact of the funding shortages is the waiting list for services. DADS calls it an “interest list,” but however you sugarcoat it, 24,000 mentally retarded Texans are in limbo, 10 percent of that number in Bexar County. Rix, Amy, and Barbara who were admitted to SASS and Scott, who went into foster care, had to wait an average of two years to get a slot of their choosing. During that time, they received no services. They were luckier than others, however, who had been on the waiting list as long as 12 years. This spring, the legislature started whittling away at the waiting list, appropriating $79.5 million to reduce the list by more than one-third by the end of fiscal year 2006-07. In two years, 14,000 mentally retarded people could still be on the list.

Several bills also were introduced that would have privatized state schools and hospitals. Entities wanting to buy state schools would have to show they could save 10 percent of the current operating budgets; that provision was later amended on the floor to 25 percent. The bills failed. There were no bidders for state hospitals, and only two for state schools, Truitt says, “and they didn’t meet the quality standards.”

State Representative John Davis, a Republican from Houston who serves on the House Appropriations and Human Services committees, sponsored one of the bills, saying a private system could provide “flexibility and creativity” with strong government oversight. Yet mental-retardation advocates on both sides of the state-school issue say existing private and state facilities aren’t monitored enough in most cases, once a year. Several large private corporations, including Educare, already own hundreds of group homes and institutions in Texas, and advocates wonder about the ethics of earning hefty profits from society’s most vulnerable citizens. To save money, the companies would have to cut wages or care, or both.

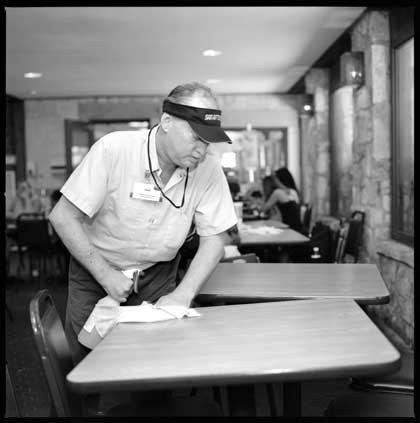

| Steve lived in public and private institutions until moving into a San Antonio group home less than two blocks from his parents’ house. He worked at Sea World and now earns money in the cafeteria at the San Antonio Zoo. He won medals in several sports at the Special Olympics, attends church, and takes vacations to Disneyland. “Steve gradually changed from a person who had just existed to a young man who now lives life,” his father, Bernard, says. |

“In Pennsylvania, we kept them out of the state,” says Steve Eidelman, executive director of the Association of Retarded Citizens. “We set a limit on their earnings. They couldn’t make a profit, so they didn’t come. Are the people doing this inherently bad? No. But 60-70 percent of costs are wages and benefits. To save, you’re not going to train them as well or pay them as much. To have a profit incentive isn’t good.”

It’s been nearly 160 years since the first institution for people with mental retardation opened in the wing of a state school for the blind. Over the next century, families who could not, or would not, care for their mentally retarded children sent them to these facilities, which were initially thought to protect the vulnerable from the dangers of society, but in the early 20th century functioned to hide them from public view... Go to part 2 of "Life at the bottom."

By Lisa Sorg