The Alamo City has seen a Manifest Destiny-like northbound sprawl, feverishly gobbling up land for construction past Loop 1604 and beyond.

At the same time, over on the East Side of the city near downtown, neighborhoods languished as crime and poverty rates soared.

That's now starting to change.

Five years ago, San Antonio Mayor Ivy Taylor was a councilwoman representing the East Side and, following on the footsteps of her predecessor Julián Castro, she opened the floodgates to revitalization efforts in some of the Alamo City's most underserved communities.

"I am personally very engaged in this effort," she told the San Antonio Business Journal last summer. "We have a tremendous opportunity to create a model of comprehensive community development that can be replicated in San Antonio and in other cities throughout the nation."

A wave of redevelopment has occurred in historic East Side neighborhoods, bolstered by none other than the nation's top leader.

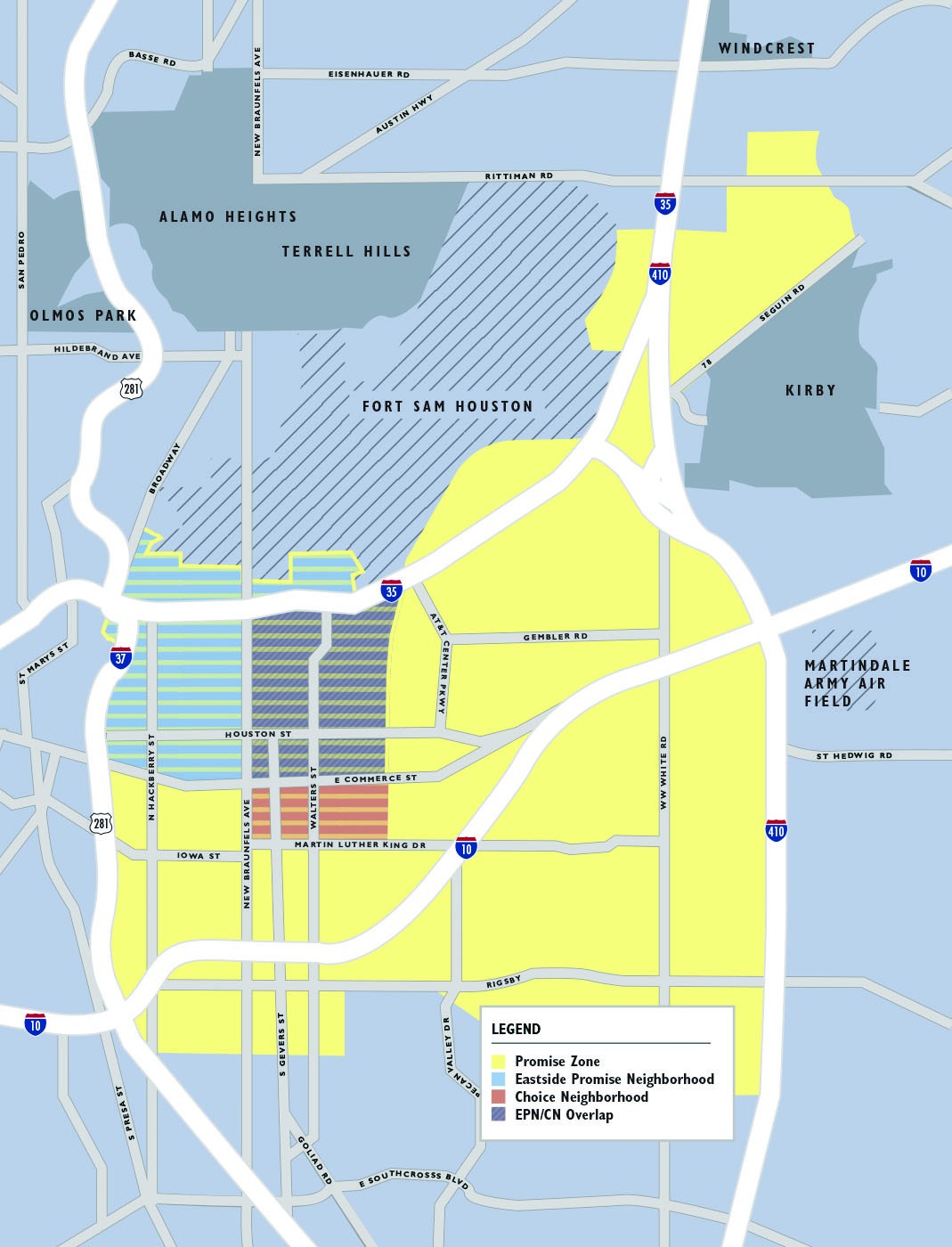

Two years ago, President Barack Obama designated a 35-square-mile area from Interstate 37 to Fort Sam Houston and AT&T Parkway to East Commerce as one of the first "Promise Zones" in the country.

The designation brought access to exclusive federal grants in an effort to improve the lives of more than 64,000 San Antonians who face a 35 percent poverty rate in what are still considered some of the Alamo City's most rundown and violent neighborhoods.

It hasn't completely turned around, but in many aspects, the East Side is starting to look like a shell of its former self.

Private development has spilled into neighborhoods in and around the Promise Zone, creating a real estate boom and bringing an influx of new homes and businesses.

Signs Of New Life

Wheatley Courts is the bull's eye of what's called the "Choice Neighborhood."

The former public-housing complex is surrounded by a high chain-link fence and the troublesome block that used to be the epicenter of gang activity in the neighborhood is now comprised of large piles of dirt and deep holes in the ground to make room for new housing.

The renovation of Wheatley Courts from a public-housing project into a mixed-income housing complex for more than 500 residents is the anchor for East Side revitalization through the Promise Zone initiative.

The massive undertaking still faces challenges, as highlighted in a 2012 study by the San Antonio Housing Authority for its "transformative" plan for the Wheatley Courts neighborhood.

In the study area that is bounded by New Braunfels Street to the west, Interstate 35 to the north, railroad tracks to the east and Martin Luther King Drive to the south, 57 percent of the housing stock was built prior to 1959 and there are around 180 vacant lots.

Violent crime has also been a perennial dilemma. It usually stood at twice the overall city rate, according to the SAHA study. Not anymore. All crime has dropped by seven percent, according to the city.

It may be way overdue and change is coming about gradually, but there's a certain buzz that positive change is palpable in the East Side.

"First of all, crime has been decreasing because of the renewed focus on community policing. We have neighborhood watch programs. The police department is engaging more with the community and building trust," said Mike Etienne, director of the San Antonio EastPoint & Real Estate Office, which coordinates revitalization efforts in the Promise Zone between the city, developers and a host of nonprofit agencies.

Then there are high school graduation rates. For instance, the SAHA study found that 43 percent of adults didn't graduate high school, compared to Bexar County's rate of 18.5 percent.

But that's starting to change for today's youngsters.

"The high school graduation rate has increased, especially at Sam Houston High School, which was 46 percent, and has gone as high as 84 percent," Etienne said.

Part of the reason for this drastic increase is the federal Promise Neighborhood Grant. The monetary infusion has been used to pay for tutoring and coordinating internships. And the San Antonio Independent School District has used it to hire more experienced teachers.

Education is key to future prosperity, which is why revitalization efforts need to focus on workforce development, Etienne said.

"There's a large percentage of East Side residents who have significant barriers to employment, like adult education, criminal backgrounds, ESL, daycare, transportation and so we do have barriers," he said.

In response, the city has tapped Alamo Colleges to develop a strategic plan to address those barriers, while St. Phillips College provides adult education and GED certification.

"It's critical that the residents have a job, that they have income to pay for houses that we build ... to improve the quality of life for their families," Etienne said.

Beyond injecting new life into the former Wheatley Courts trouble spot, some pockets of the East Side are seeing an infusion of modern housing investment.

At Cherry and Burnet streets, you'll find a sleek new high-end apartment complex at the foot of the Hays Street Bridge called Cherry Street Modern, featuring 12 units sold out before construction was even finished last year.

Units at the modern-styled box-like complex, which sits across the street from the newly opened Alamo Brewery, sold for about $177,000 to $190,000 apiece.

Angel Lopez, a 32-year-old system administrator at Rackspace, was quick to grab one.

"The main attraction to me was the contemporary style. This place had a lot of what I was looking for," Lopez said.

He said the rooms were laid out just right, the kitchen was big and open, there was a smooth floor of stained concrete and it featured a peaceful view of downtown.

"I enjoy the small-town feel of this neighborhood. The many styles of architecture found in this neighborhood are indicative of its rich history," he said.

As he sees it, revitalization has been great for this area.

"The new businesses opening in this area have definitely brought more people to visit the East Side. I'm happy to witness it," he said.

Troubled Transformation

Lopez and Promise Zone backers may be happy, but that's a feeling countless other East Side residents have yet to experience.

For 80-year-old Mildred Bailey, who lives near the railroad tracks by the intersection of St. Charles and Rudolph streets, the flood of revitalization leaves only standing water — literally.

In late March, following strong rains, Bailey stood outside her Dignowity Hill house stamping down wet gravel laid down by the city in its effort to soak up the standing water.

"The water would come around the corner and it would just stand," Bailey explained. "It would be so high because it rained just about two or three days ago. So it's kind of gone down some."

There are no curbs on her street or sidewalks, and brown murky water filled potholes. The problem escalated during the workweek.

During the summer, brush in the area draws stray dogs and cats while stagnant water attracts mosquitos and other pests.

Bailey has lived here for more than three decades and has yet to see her quality of life improve.

"Sometimes I have to go to the doctor and I have to call the VIA bus transit and they'll pick me up, but they have to come way up there," she said, pointing to an alley. "I can't walk out down here because of the mud and water."

Yet she's practically down the street from the new Cherry Street Modern complex, thus highlighting the apparent hodge-podge nature of the East Side comeback.

"All this different development, it's random," said Juan Garcia, a resident of Dignowity Hill and former president of its neighborhood association. "It's organic, but really random."

On any given street, overgrown vacant lots with leaning chain-link fences sit next to rickety homes making one wonder how they're still standing. That's a stark contrast with the smell of fresh sawdust at historic houses being refurbished for sale just down the street.

But even the vacant lots and rundown houses have something in common with structures undergoing renovations: for-sale signs.

"Prices have more than doubled in the seven years I've lived here," Garcia said.

For instance, five years ago, vacant lots were selling for $10,000. But now, it's not uncommon for lots to sell between $40,000 and $60,000. And then there are the houses.

"People are flipping properties like crazy. One property was valued at $90,000. This guy turned it around and sold it for $119,000," Garcia said. "And the guy fixing it up right now is going to sell it for $350,000."

While the nuts and bolts of renovating East Side homes – many are considered historic – are difficult in their own right, maneuvering between historic commissions, building boards and zoning requirements while applying for city incentives is a tall order.

Syngman Stevens, who grew up in Dignowity Hill, said he meant to renovate a house he bought four years ago and was ready to invest $250,000 to fix it up, but cost estimates came in at more than $500,000. Stevens, a businessman who owns Tong's Thai on Austin Highway said all his efforts ended up in yet another vacant lot.

"What I find is big business or commercial contractors can maneuver easier than someone in the neighborhood that's trying to be engaged," Stevens said.

Because of the high price, he planned to demolish the home, which was considered historic, and build anew. But he actually couldn't do that on his own – he had to get approval from the city's Historic Design and Review Commission. He didn't have any luck.

"The average home here was $50,000. For most people, economically, fixing them up is a hardship," Stevens said. "But I was ready to put $250,000 in this home and $250,000 in another I owned."

He appealed to the Building Standards Board, which allowed the demolition, trumping the HDRC for public safety reasons.

If the HRDC had approved his plans he could have built a new house as originally planned, but instead, since the building was condemned, he'll have to wait five years per city regulations if he still wants to build on the property.

"They was against me. They wanted to fight, but they lost the war because now we got another empty lot," he said.

And there are a lot of empty lots. Garcia estimates there are at least 100 in Dignowity Hill alone.

"None of this was a problem until revitalization. What I see isn't fair to some of the people who live here. The city is writing citations right and left, which I like. But I worry about it," he said. "I have resources, but some of my neighbors don't."

So the nature of the East Side's rejuvenation is spotty. While the Promise Zone is seeing an influx of federal money and private developers are pumping cash into neighborhoods like Dignowity Hill, others have yet to reap the same benefits.

Priority Issues

Another obstacle in the effort to revamping the East Side is the age-old problem of drumming up community involvement – getting locals in the act.

"Residents, they are busy. They work. They have families. There is news of big activity and then it wears off, but the question is how do we keep it going," Etienne said. "Ultimately, we want to get the residents to take ownership, where they will make sure that if they see a pothole they are empowered to call the city and say 'Look, there's a pothole in the street. Can you come and fix it?'"

Potholes, like the ones staring at Bailey when she walks out of her house. Not that they'll get fixed any time soon. City officials told her the streets will need to be completely redone to fix drainage problems – not expected until 2017.

"This has been a problem since I moved in more than 30 years ago. I even talked to (city manager) Sheryl Sculley and she told me to get back with the guy who was working with her," Bailey said. "But for some reason he left the city and I never did hear anymore about it."

Bailey's even attended a public meeting put on by the Mayor's Task Force on Preserving Dynamic and Diverse Neighborhoods. The task force's goal is to increase investment in inner city neighborhoods without forcing locals to flee – gentrification.

Garcia attended one of those public meetings, too.

"No one was allowed to ask questions. People who wanted to speak got three minutes," Garcia said. "It was one-sided discourse."

The Texas Organizing Project, a member-driven advocacy group, has thus far been skeptical of the task force's priorities.

Mu Son Chi, the group's Bexar County director, said the task force has a draft report full of recommendations for preventing gentrification in spots the city has identified as long-neglected neighborhoods.

"We need to get recommendations to make sure our communities are not displaced. There needs to be a policy solution," Chi said. "Obviously, there's a need to track displacement but without policy to help prevent it they are making displacement a forgone conclusion. That's a problem."

Chi wrote a letter to members of the task force urging them to place more importance on preventing gentrification, but also to address those nagging problems like curbs, sidewalks, streetlights and drainage.

"These infrastructure problems are a result of not a natural disaster but a political disaster that happened over long period of time," Chi said. "These residents deserve basic infrastructure. It's a matter of equality and justice and dignity."

But with increasing property value attracting more development, low-income residents who have lived in the historically neglected neighborhood long before city leaders and developers began paying attention could soon end up with the short end of the stick.

"If I drive to the North Side I see streetlights every 30 yards, proper drainage and sidewalks," Chi said.

Probably something most people

in the nation's seventh-largest city would expect.

Yet it remains a decades-long elusive dream for folks like Bailey.

So, yes, good things are happening in the city's long-neglected East Side. It seems poised for a definitive transformation. But will change benefit all or just some, making this area just the city's latest gentrified hot spot?