When news broke that the Supreme Court had struck down the ban on same-sex marriages, Donna and Jordan Reed were the second couple to apply for a marriage license at the Bexar County Clerk's office.

Donna, 67, and Jordan, 69, have been together for 47 years. Jordan said they've been "quietly out," primarily wrapped up in the normality of their day-to-day lives.

"We haven't been politically active," Jordan told the San Antonio Current. "We've never spoken to a congressman."

But the Reeds realize they owe their ability to marry to "all the people who have been out there doing the real footwork." She's talking about LGBT activists who battled for decades in city streets and courtrooms for the hearts and minds of decision-makers and the general public back when the cause didn't have wide support.

In San Antonio, LGBT activists see the Supreme Court's ruling as a monumental victory, but one whose seeds were sown years ago. And though their work isn't done, many members of the LGBT community have used the landmark ruling to reflect on how far they — and this city — have come.

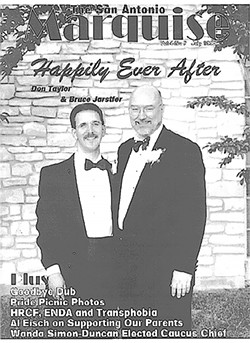

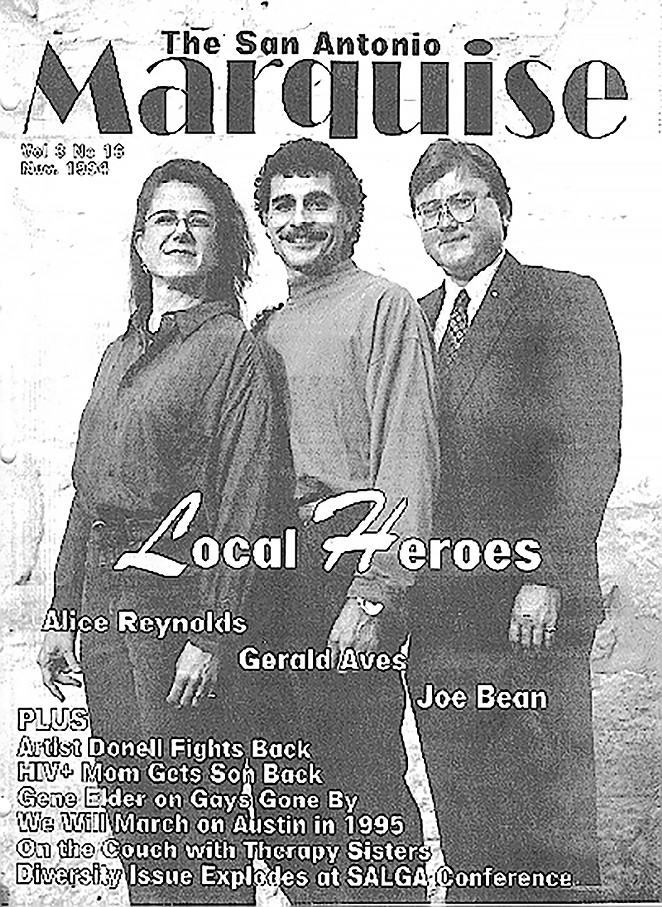

"It was a long time coming. We've been working on this for a long, long time, over three decades," said Ted Switzer, former publisher of The Marquise, a San Antonio LGBT magazine in the 1990s. "It may seem fast to some people who are not activists, but ... it's been a long time."

'Closeted, Closed, Regressive'

Despite years of toil in the trenches, scarcely anyone would have predicted the Supreme Court's decision even just a few years ago. Many activists said that for so long, national marriage equality never seemed tangible.

"I could not envision this in my lifetime," Brad Veloz, 69, a former co-chair of the San Antonio Lesbian and Gay Assembly, told the Current. "I could not see it. I felt that we had too many obstacles to go through to get to marriage equality."

LGBT activists remember San Antonio as a very different town than the one now adorned in rainbow flags.

Graciela Sanchez, director of the Esperanza Peace and Justice Center, recalled SA as "pretty much a closeted community" when she returned to her hometown after graduating from Yale University.

"I came into this work in the early 1980s, right out of college coming back to San Antonio, where being out is a scary notion. Nobody talked about it," Sanchez said.

Some cite San Antonio's deep Roman Catholic roots and the "Military City U.S.A" moniker as main reasons for its traditional lack of inclusivity.

Switzer, who moved here in the 1990s, described SA as a "very closeted, closed, regressive sort of town."

Gene Elder, an LGBT activist and artist who runs The Happy Foundation, a non-profit archive of San Antonio's LGBT history, can recall even further back in time. He said that the 1970s were, for a time, a period of great progress.

Back then, Elder observed the comings and goings of the community as the manager of the San Antonio Country, an iconic gay club often raided by law enforcement.

"Since I saw the situation and the gay community daily ... I got to see how people changed and were willing to have gay friends and come to the club with us," Elder said. "Things were going great until AIDS. Then the religious hatred really came out in all its ignorance. And we lost really beautiful men ... Not just physically, but spiritually beautiful."

Elder pointed to one night in particular in 1978 that galvanized San Antonio's LGBT community: when Anita Bryant came to town.

Bryant, a former Oklahoma beauty queen turned orange juice huckster, went on barnstorming tours in the late 1960s and 1970s to sing gospel and rail against the "evils of homosexuality."

She came to San Antonio in late February of 1978. And the sheer presence of Bryant, the woman who once said "if gays are granted rights, next we'll have to give rights to prostitutes and to people who sleep with St. Bernards and to nail biters," invigorated San Antonio's LGBT community.

"Anita Bryant coming to town brought the issue up front and center," Elder recalled.

Arthur "Hap" Veltman, the LGBT activist, entrepreneur and namesake of The Happy Foundation, raised funds to take out a full-page ad in the San Antonio Express-News for Bryant's arrival. Veltman, who died in 1988, wrote the ad copy himself:

"It is an individual decision to fight for human rights for every citizen in this nation. Those rights were meant to exist under our Constitution, for without them, we begin the forfeiture of an equal opportunity under the law for designated groups. May enough individuals speak out against this injustice, and play a positive role in overcoming a tragic turn from liberty."

Protesters picketed outside the concert and Elder passed out an "Anita Bryant Prayer," which read in part:

"'Remember the Alamo' is not only our call to arms, but a constant reminder that our forefathers fought for freedom from opposite sides of the church walls. The blood runs deep into our soil on both sides and we are slowly learning how to live in peace, and to love each other once again. Forgive us for not taking up your sword against our gay brothers and sisters. We can not afford to once again tear our city into pieces."

Growing Pains

Though San Antonio's LGBT community grew and became more vibrant in the 1990s, there was also tremendous conflict caused by rifts between and within activist groups, as well as institutional persecution from lawmakers and law enforcement.

"The '90s were kind of odd for the U.S. as a whole. In this country, we were experiencing some really tremendous backlash with LGBT folks," Veloz said. "There was this cloud hanging over the LGBT community, especially for Latinos. San Antonio was not immune to that."

In 1994, four San Antonio lesbians — Elizabeth Ramirez, Kristie Mayhugh, Cassandra Rivera and Anna Vasquez — were charged with aggravated sexual assault of a child and indecency with a child.

The "San Antonio Four," as they became known, were all convicted, with the defendants' lesbianism front and center during the trial. They spent over a decade in prison before being released in 2013 due to advances in forensic technology, which proved their innocence.

"It was a witch hunt," Sanchez said. "They wasted away so many precious years of their life."

Through the 1990s, the San Antonio Police Department ran sting operations in public parks to catch gay men having sex.

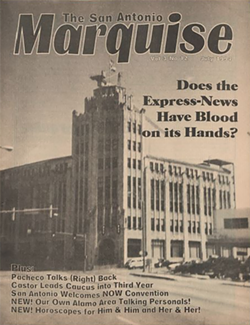

Those who were arrested, typically on charges of public lewdness or indecent exposure, had their names published in the San Antonio Express-News.

One of them, Benny Hogan, was fired from his job at USAA after his name appeared in the paper. He hanged himself in his garage the next day.

Switzer described Hogan's suicide in the July 1994 edition of The Marquise:

"While 12,000 of us were together at the Gay Pride Picnic celebrating the social and political gains of the 25 years since Stonewall, Benny Hogan, closeted and all alone, killed himself. Hogan was the victim of the San Antonio Express-News selective policy of publishing articles about 'park stings' ... and printing the names of those arrested."

Maria Salazar, a San Antonio-based family law attorney, remembered the 1990s as a time when LGBT community members "didn't think that law enforcement would offer them protection."

Who were the cops serving and protecting back then?

"People were afraid of coming forward. I remember being out at the clubs, out on the strip, and making sure people got back to their cars so they wouldn't get harassed. We had to look out for one another," Salazar said.

Salazar, 50, thinks the relationship between the LGBT community and SA law enforcement has improved. But there's also been a sea change in the community's ability to organize and wield power with decision-makers, Salazar said.

"At this point, I see candidates reaching out to ... groups that are progressive asking 'How do I get your support? What are the issues that are important to you?' So they're coming to us instead of us coming to them," Salazar said. "I'm seeing San Antonio just be a lot more organized politically on issues that are important. That's a big difference."

Struggle Not Over

Mark Phariss, a corporate lawyer in Dallas, was one of the plaintiffs in a 2014 suit to strike down Texas' same-sex marriage ban.

Phariss and the three other plaintiffs, including his partner of 18 years, Vic Holmes, won the case, but U.S. District Judge Orlando Garcia also issued a stay pending an appeal, which kept the ban in place until the Supreme Court's ruling.

Phariss lived in San Antonio between 1985 and 2001. In 1997, he served on the Board of Governors for the Human Rights Campaign in San Antonio, when he started working on the city's first non-discrimination ordinance to ban the city from discriminating against LGBT workers.

Phariss, 55, assembled a sort of NDO scrapbook for City Council members, presenting each of them with a suite of information on why such protections were necessary and how other cities had implemented them.

Pharris secured commitments from eight City Council members and the mayor — more than enough to pass the NDO.

But when the meeting happened on January 29, 1998, anti-LGBT protesters swarmed City Hall, daring the City Council members to support the NDO.

"At that meeting, it was just hateful. We were way outnumbered," Pharris said. "The things that people were saying ... were just incredible. I was just incredibly devastated."

The NDO that Phariss drafted never got a vote. Phariss called it "one of the most discouraging days of my life."

It was impossible to imagine, then, that less than two decades later, not only would San Antonio pass an NDO, but Pharris could also marry Holmes, whom he met in SA.

"The environment that I grew up in, I was absolutely convinced that if someone found out I was gay, I would lose my job, I would lose my housing, my relatives would disown me and I'd be homeless on the street," Pharris said.

"The concept that I could marry the person I love and have friends and family attend and it be perfectly accepted by the government, that wasn't even on my radar," he said.

But even as they celebrate the Supreme Court's decision, advocates caution that their work isn't close to finished.

"There's still so much more that has to be done," Sanchez said. "We've heard from our Texas leadership that they're going to allow for discrimination to take place if people think that their religion doesn't allow for [same-sex marriage]."

And beyond protecting newly-granted rights, activists now point to tilling vast but fertile territory with housing, employment and spousal benefits.

"Bringing protections to LGBT folks in employment nationwide, as well as locally in housing and employment, is the next step," Veloz said.

"I think that's our next battleground," he affirmed.