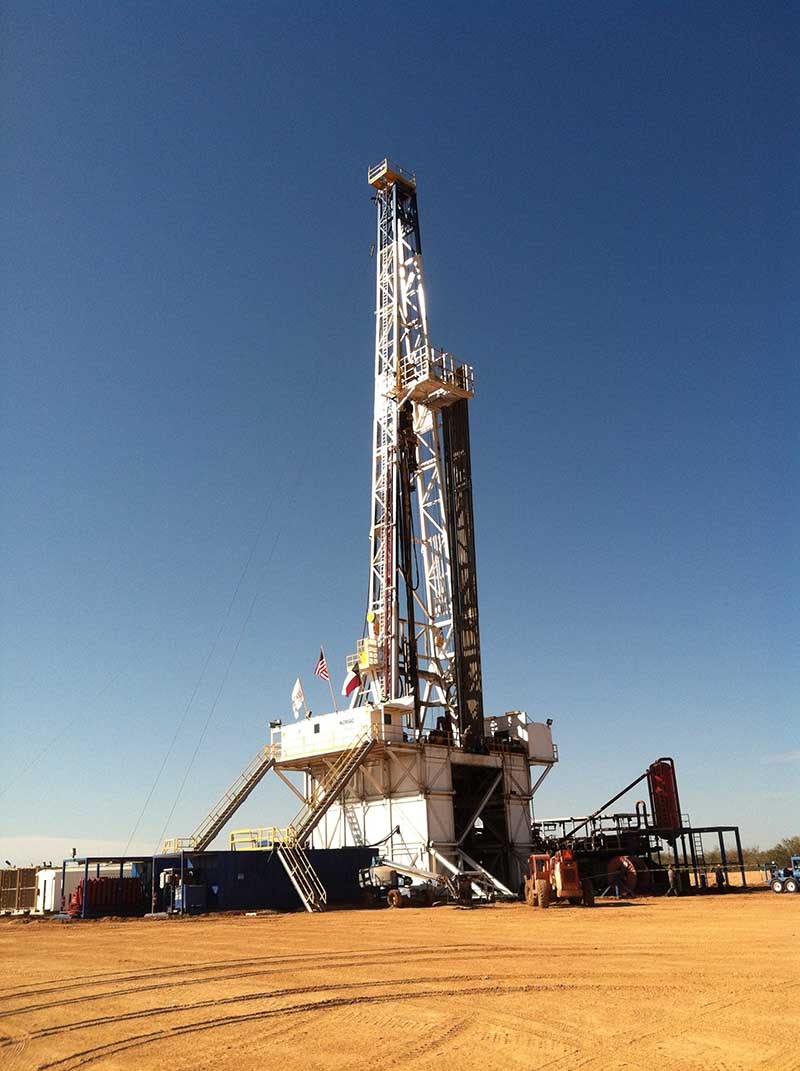

The U.S. has undergone the kind of dramatic makeover that's typically reserved for TV reality shows. The mining of unconventional shale gas, light and tight oil–enabled by horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing–has sparked an energy revolution.

In 2005, when these unconventional wells were first drilled in the Barnett Shale basin around Dallas-Fort Worth, America was the world's largest oil importer and domestic production had been in decline for three decades. That's now reversed. We're producing 8.5 million barrels daily and until recently many expected us to break the U.S. production record of 9.6 million barrels set in 1972.

Gas output has increased by one third and total petroleum output (including oil, gas and condensates) by almost three-fourths in just six years. We now drill more oil and gas than anyone in the world–topping even Russia and Saudi Arabia. Two-fifths of it comes from Texas. The energy industry employs twice as many people as it did nine years ago, and it contributed 0.3 percent to last year's gross domestic product.

There's no denying the turnaround; the question is how long it will last. Texans are more familiar than most with boom-bust cycles, so the quantity of sunshine being bussed up our backside might raise an alarm or two. Much of the boom is fueled by cheap credit, unrealistic expectations and lots of excess capital swishing around in search of good yields.

"Very little of this would be going on if you had to pay 3-4 percent interest on money that people gave you," said Houston energy consultant Arthur Berman. "Whenever interest rates are really, really low, people spend money on really stupid stuff. And most of these companies are going to pay you an interest rate that beats the pants off a savings account or a CD [certificate of deposit]. So the world has found what they consider a reasonably secure way to get anywhere from 6 to 9 percent interest."

The Price of Being Different

The fundamentals of unconventional wells are distinctly different from those of conventional wells, and this has contributed to the shale bubble's inflation. Unconventional wells are expensive to drill and run down quickly, and fracking, as it's known, requires constant capital investment to maintain production levels.

Fracking wells are drilled at an angle and chemical slurries are pumped deep into the ground to break up the thick shale deposits, freeing the gas and oil trapped inside the rock. It's an expensive process. The cost of drilling a horizontal well averages $6-$8 million, compared to $1 or $2 million for a conventional well.

The wells gush hard when they're first drilled, but lose around 40 percent of their capacity each year. By the end of the third year the flow is one quarter what it once was. That means to maintain production levels companies have to keep drilling more wells. In fields like the Eagle Ford and Bakken, four-fifths of new production replaces the output from already depleted wells. In the industry it's known as the Red Queen syndrome, after Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking Glass character, who complains, "It takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place."

The best output comes from "sweet" spots, which are twice as prodigious as the rest of the field. Companies attempt to locate these first since they're the most profitable wells to drill. But the fact that the best spots go first only exacerbates the depletion issue since those wells become increasingly more difficult to replace.

"As you move out you start dealing with fringier and fringier acreage. The costs of the wells generally go up because you're drilling longer laterals with more fractures," Bill Powers, author of Cold, Hungry and in the Dark: Exploding the Natural Gas Supply Myth, said. "You can keep the production stable as you move out, but eventually geology trumps technology, and the wells get more expensive while putting out less."

This explains the hushed skepticism among industry insiders. In a series of emails among industry executives exposed in 2011 by The New York Times, an official at IHS Drilling Data mused, "the word in the world of independents is that the shale plays are just giant Ponzi schemes and the economics don't work."

It's important that the companies active in the shale keep drilling quickly enough to maintain or increase production. That hides the unprofitability of the wells and keeps their debt-fueled expansion going. The problem is that once production levels stagnate, Wall Street frowns, and those "buy" analyses turn upside-down. Then the money to fund all that drilling dries up. That's why the pressure is on to maintain the hype. Bloomberg reported in October 2014 that 62 of the 73 shale drillers gave investors resource estimates on average 6.6 times higher than proven reserves reported to the Securities and Exchange Commission.

That's the nature of the game, according to former investment banker and energy-industry analyst Deborah Rogers. "Publicly traded companies have two sets of economics: field economics for oil and gas companies–what are the underlying wells doing, what are my costs on the field–[which] are totally separate from what I call 'street economics,'" she said. "That's where you start seeing creative accounting in order to keep the analysts interested in your stock, keep your financials looking like you're meeting those metrics and keeping your bankers happy. ... "Those two things don't necessarily jibe."

Fake it Till You Make It

So far the spin job has worked. More than $16.3 billion was invested in mutual and exchange-traded funds focused on energy companies in the first seven months of the year–twice as much as the same period last year, according to analysts Strategic Insight.

Yet the underlying figures are ominous. Shale debt has doubled over the last four years while revenue has inched up just 5.6 percent, according to a May Bloomberg analysis of 61 shale drillers. A dozen of these independents were spending at least 10 percent of their sales servicing their debt. Some, like Forest Oil, Goodrich Petroleum and Quicksilver Resources, were paying interest expenses in excess of 20 percent. Many companies are spending more than they're taking in, and this negative cash flow has not improved, even as investment continues to pour in.

"You can have negative free cash flow for a short period of time, but when it turns into a long-term pattern there is something very wrong," Rogers said. "The other problem with these companies is that most of it is junk debt. You've got low-quality credit and very high levels of it."

This is such speculative debt that banks can't buy it, leaving companies to lure other investors with high yields. In the first quarter of the year independent U.S. oil and gas producers sold $2.3 billion of such bonds, about half of all the corporate bond debt they issued. About 80 percent of the 115 exploration-and-production firms Moody's Investors Service follows and 70 of the 97 companies Standard & Poor's evaluates are junk-rated.

Independents aren't the only shale players who are struggling. During the past 18 months, major players have taken huge write-downs on shale. Sumitomo took a $1.55 billion write-down on its joint venture with Devon Energy in West Texas' Permian basin. In April, BP wrote off half-a-billion in Ohio. Last year Shell wrote off $2 billion and sold 100,000 acres it had acquired in the Eagle Ford basin. Marathon also wrote down $340 million of acreage in counties like Bee, DeWitt, Lavaca and Wilson.

Of course, the major oil companies were latecomers to the shale party. They didn't tend to get the prime acreage or the low prices that help ensure success for those early to the play. Nor are the majors necessarily built for it. "The business model that supports the major oil companies is predicated on size and scale," said former Shell CEO John Hofmeister. "That's the antithesis to shale plays where the independent operator has a business model that is based on move quick, drill it now and get on to the next one."

The question remains–do these smaller independents have the wherewithal and, more importantly, the capital, to withstand the incipient fall industry analyst Tim Morgan described as "this decade's version of the dotcom bubble?"