The man’s voice over the intercom sounded so slurred, the cashier at Chacho’s & Chalucci’s could barely understand him. So someone else inside the green Cadillac tried to shout food orders over the drunk driver, while a manager made his way outside the restaurant to check on the busy drive-thru lane. As the bars approached last call on February 28, 2014, the scene wasn’t exactly unusual for a late-night, early-morning shift at the 24/7 Tex-Mex joint on San Antonio’s Northeast Side – records show the cops have been called out to that Chacho’s location at least 220 times since 2012.

Whitney Jones, sitting in the back of that Cadillac, had just wanted some food after a night of drinking and shooting pool with her cousin, who sat next to her in the back seat, and her brother, Marquise Jones, who sat in the front passenger side. An acquaintance she barely knew, Fabian Garza, had offered to drive the crew around for the night, but now he sat in the driver’s seat drunk, confused, and making everyone nervous.

First, Garza started to take off without their food and then, as he moved the Cadillac back in line, he bumped into a white SUV. A woman got out and started yelling about damage to her car as San Antonio Police Department Officer Robert Encina, working an off-duty security job at the restaurant in full uniform, approached the Cadillac. Encina would later testify he could smell booze on Garza’s breath as he ordered him out of the vehicle.

From the back seat of the car, Whitney could see her brother tense up. With a rap sheet that included theft, drug and assault convictions, Marquise, 23, had plenty of prior run-ins with the cops. According to an affidavit his sister later filed in court, he’d last checked in with his probation officer the previous morning. His family claims he’d actually encountered Encina at the restaurant two weeks before the drive-thru fender bender and came away saying he’d felt harassed by the guy. Later, in a court deposition, Encina said he'd never seen Jones before that morning.

As Encina struggled to handcuff Garza outside the car, Whitney could see Marquise fidgeting. It looked like he was about to run. “Marquise, you’re good, you just reported this morning, you’re OK,” his sister told him, according to her affidavit filed in court. She tried to assure her brother he had nothing to worry about.

What happened next depends on who you believe.

Encina told investigators that morning that as he was cuffing the driver, he saw Marquise “moving around a lot” inside the car and reaching into his pockets. Encina claims he yelled, “Get your fucking hands out of your pockets,” though none of the other witnesses who gave police statements that morning recalled hearing anything like that. “I got an uneasy feeling about this situation,” Encina said in his sworn statement. He thought Garza was “trying to distract me so the passenger could get out of the car to shoot and kill me.” Garza and Marquise hadn’t even met until that night.

In his statement, Encina claims he spotted a silver or chrome revolver in Marquise’s hand as he opened the passenger door, and that Marquise “looked back over his shoulder at me” when he started to run. Encina fired eight rounds, one of which struck Marquise in the back. He collapsed dead on the pavement as he ran toward the street.

That, or some version of it, has been the official SAPD account of Marquise Jones’ death ever since, despite five eyewitnesses who that morning told investigators they never saw him with a gun. SAPD eventually concluded that Encina, a six-year department veteran at the time of the shooting, was justified in killing Jones, and nearly two years after his death, a grand jury cleared him of any wrongdoing. He remains on the force.

Yet three years after the shooting – which triggered demonstrations by Black Lives Matter activists, T-shirts and signs emblazoned with the words “I Am Marquise Jones,” and even a “die in” protest at North Star Mall that resulted in two arrests months after Jones’ slaying – critical details in the case remain murky. Advocates for police reform, who have stood alongside Jones’ grieving family while demanding answers outside City Hall, argue that’s largely because of how SAPD investigated the case. They point to a gun police claim was found some 15 feet away from Marquise’s body – a weapon that doesn’t match Encina’s description, and, according to deposition testimony from investigators filed in court, was never tested for prints or DNA or any other physical evidence, a weapon that investigators admitted they could never definitively tie to Jones.

A defense expert in the case, meanwhile, says lab reports indicate Jones had gunshot residue on his left hand, a potential sign he may have handled a gun sometime that day (the gun found near Jones hadn’t been fired).

Critics also point to two eyewitnesses who came forward two years after the shooting, a Chacho’s employee and customer who claim police never so much as asked them for a statement the morning Jones was shot. One says he was parked right next to the car Jones ran from, and that Encina approached him after the shooting, trying to confirm that he, too, saw a gun – he hadn’t. Also last year, after the restaurant had sworn in court filings that no video or audio recordings from the morning of the shooting existed, video from inside the restaurant suddenly surfaced. The defendants continue to maintain there’s no security video of the drive-thru lanes that morning. While Chacho’s currently has security cameras in the drive-thru area of the restaurant, it’s not clear when those were installed (attorneys for the restaurant had not responded to our questions as of press deadline).

Testifying in a deposition last year, SAPD Chief William McManus acknowledged inconsistencies in the police narrative of the shooting. He even admitted that the investigation summary his department submitted to the Bexar County District Attorney’s Office was incomplete.

In some ways, the Marquise Jones case has become an awkward asterisk hanging over talks surrounding police accountability in San Antonio. To city officials, Jones died because he flashed a gun at a cop. To attorney Daryl Washington, who filed a lawsuit in San Antonio federal court against Encina, the city and Chacho’s on behalf of the Jones family, it’s evidence SAPD can’t be trusted to investigate its own.

“Based on this, I don’t trust SAPD or the DA’s office to investigate this kind of case,” Washington told the Current. In and out of court, he’s repeatedly called the Jones case a “coverup.”

In January, Washington tried to sanction the city for what he alleges was suppression of evidence in the case, a request a judge denied. Still, despite city attempts to dismiss the wrongful death lawsuit, a federal magistrate recommended the case go to trial, writing in a report, “[T]here is a genuine factual dispute regarding whether Jones had a gun and whether he made any threatening gestures to justify the use of deadly force.” A federal district court judge ultimately agreed and allowed the case to move forward. It’s scheduled for trial on March 27.

Assistant city attorney Deborah Klein told us that officials remain confident in their investigation into the Jones shooting, saying, “I’m sure how the investigation was done will be fully addressed in court.” In a prepared statement, SAPD said, “We have consistently demonstrated our abilities to objectively investigate and, when warranted, file criminal cases involving our own personnel.”

That’s not how Johnathan-David Jones sees it, especially not after the Marquise Jones case.

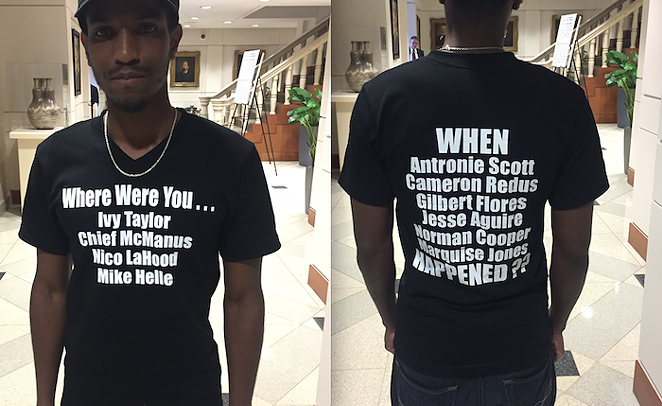

Johnathan-David (no relation to the Jones family) helped lead local activists agitating for police reforms at City Hall last year and was eventually invited onto a task force Mayor Ivy Taylor established to improve trust between police and policed in San Antonio. As Johnathan-David stood before City Council last year pushing for police reforms – including independent, outside investigations of police shootings – he wore a shirt that listed Jones alongside other high-profile victims of police violence, including Antronie Scott, an unarmed man shot and killed last year by an SAPD officer who mistook his cellphone for a gun.

“Do I have general disdain for SAPD? Of course not,” Johnathan-David said after one of those task force meetings. “But I do not at all trust how the Marquise Jones case was handled, not after what’s come out.”

To him, the investigation was either sloppy or intentionally mishandled. “It was either corrupt or incompetent,” he said. “Neither of those are good options to me.”

SAPD Detective Randall Hines got a phone call early the morning of February 28, 2014, informing him there’d been a death at Chacho’s.

As lead homicide detective on the shooting, Hines would lead one of three official investigations into Marquise Jones’ death. The second would be what SAPD calls an “administrative investigation” by supervisors assigned to the department’s Internal Affairs unit. Still, it would be Hines’ investigative summary and case file that was ultimately sent to the Bexar County District Attorney’s Office to form the basis of what SAPD calls a third “extensive and independent review” of such cases.

That morning, Hines didn’t even bother to go inside the restaurant to talk to all the employees or suss out witnesses. According to a deposition he gave in the Jones lawsuit, when he got to the parking lot at around 2:30 a.m., about an hour after Jones’ death, another investigator had already gathered up all the witnesses he needed. “I trusted him,” Hines testified. “[J]ust from my experience on the police department, I can take the word of a fellow officer as truthful.”

Daryl Washington, attorney for the Jones family, argues that police overlooked two critical witnesses they should’ve caught. One, named Lamar English, a busser at Chacho’s that night, first came forward in October 2015 and signed two affidavits for Washington saying, “I had a clear view of Marquise Jones and know without a doubt that he did not have a gun in his hand.”

English even gave a deposition last May, during which he repeated the story. He says that, aside from the commotion caused by the shooting, February 28, 2014 was pretty much like any other late-night, early-morning shift at the restaurant. “I went though my own regular procedures, closing, and doing the regular things that I usually do on my regular job,” he said in his deposition, saying none of the cops buzzing around the scene approached him for a statement.

Washington says the other witness police overlooked, James Brantley, came forward last year upon learning that a grand jury had failed to indict Encina, the officer who shot Jones.

As with most things in the three-year legal saga, it’s hard to know what to make of the English and Brantley statements because of what happened after those affidavits were filed in court.

In January, during a federal court hearing to decide whether the city should be sanctioned for failing to turn over evidence in the case, officials with the DA’s public integrity unit testified that they'd reached out to English and Brantley as soon as they learned there were additional witnesses to the shooting. But the DA’s office also had a surprise of its own: Closed-circuit security camera footage showing the inside of Chacho’s the morning of the shooting.

It was video defendants in the lawsuit had already sworn in court filings did not exist — evidence SAPD swore it had never gathered. Its very existence has convinced Washington there must have been video showing the drive-thru, too. The Jones family had agreed to settle with Chacho’s for a confidential amount back in July 2015. Washington tore up the agreement and added the restaurant back to the lawsuit last month, saying that initial settlement had been based on “fraud.”

In court, Ruben Segovia, an investigator with the DA’s public integrity unit, testified the security video had been subpoenaed from the restaurant during the grand jury investigation into the shooting. On the stand, neither Segovia nor Jay Norton, an attorney appointed to head the DA’s public integrity unit last year, could say why nobody ever told someone in the civil case about the existence of the video.

Segovia and Norton testified that they read English’s testimony claiming he saw the officer shoot and kill an unarmed Jones, and then they chose to confront him with him with video from inside the restaurant that nobody else apparently knew existed. DA officials, and now the city attorney’s office, claim that footage disproves English’s initial story – something Washington vehemently denies. Regardless, after signing two affidavits and testifying during a deposition that he saw the shooting, English (who couldn’t be reached for comment) would eventually sign an affidavit with the DA’s office recanting his original story.

Washington was fuming both in front of the judge and outside the courtroom, convinced English had been pressured to change his statement. “He was harassed, his job was in jeopardy,” Washington told the court.

Brantley, however, does not appear to have changed his mind. Sometime after Washington filed his affidavit in court last April, the DA’s office tracked him down for a statement. In a 16-minute recording of his conversation with investigator Segovia obtained by the Current, Brantley says he was parked right next to the Cadillac Jones tried to run from in the drive-thru lane that morning.

Brantley tells the investigator he could clearly see Jones inside the car before the shooting. “I could tell he (Jones) was getting scared,” he says. “Maybe he had a warrant, I dunno.” Brantley says he kept thinking, “Bro, don’t even run.” And then, that’s exactly what Jones did. Brantley says he was so close to the gunfire his ears were ringing afterward.

When the shooting stopped, Brantley says he saw a Chacho’s manager detain the driver that Encina had been trying to handcuff, adding, “I didn’t understand that shit, either.” That employee was the only other witness to the shooting who told investigators that morning he saw Jones with what “looked like a handgun.”

Brantley says that as he sat in his car, Encina ran up to him and kept asking, “You seen the gun, right?” He says that when he told him no, Encina made a face. “I guess he thought I was going to agree.”

A report by retired Austin police detective Jerry Staton, an expert witness Washington hired to review the Jones case, says it’s “extremely troubling” Brantley and English weren’t interviewed at the scene. Staton also wrote that he was troubled the investigation SAPD presented to the DA’s office glossed over glaring inconsistencies that should’ve been resolved through further investigation before closing the case – or at least referenced in the report he submitted to the DA’s office. Staton concluded that, “more likely than not, one or more members of the SAPD tried to conceal evidence in this investigation that would have contradicted Encina’s version of events.”

Plus, Staton writes, even if you believe Encina’s version of events, his actions were still troubling. Investigators only found three of the eight bullets Encina fired into the dark that morning. One traveled through Jones’ back, perforating a lung and lacerating the right atrium of his heart before lodging somewhere in his chest. Two more bullets hit a suburban parked in the Chacho’s lot. “There could have been innocent persons concealed by the darkness and in direct line of fire from Encina,” Staton wrote in his report.

SAPD Chief William McManus largely kept quiet about the Jones case until a January 2016 city council briefing on some reforms at the department. He struck a defensive tone when the case came up: “Mr. Jones had a gun, the officer saw him with the gun, an independent witness saw him with a gun.”

Even as the case approaches trial next week, the surprises keep on coming. On Monday, in yet another twist, San Antonio City Manager Sheryl Sculley sent out a memo informing the mayor's office and city council that she’d hired an outside law firm to conduct a "thorough review" of SAPD’s investigation into the Jones case "out of an abundance of caution."

Sculley's memo contained yet another late-in-the-game revelation: the city is now claiming that the gun found 15 feet away from Jones was actually tested for prints but came up with nothing. It's unclear if that reversal could further stall a trial in the case.

To Washington, the gun police say they found near Jones’ body has become a convenient distraction, a way to dodge serious questions in the case – a gun that (until Monday, at least) police say wasn’t tested (investigators testified that a “patina” made it unlikely to render prints, so they didn’t even try), multiple witnesses who say they never saw Jones turn toward Encina or wield a weapon, witnesses police failed to question, and a video that mysteriously showed up years after the Jones family was told it didn’t exist.

“Don’t get me wrong, we’re not saying Marquise had a gun,” Washington said. “But even if there was a gun and he was running away from a scene he thought was dangerous, that is not enough to shoot and kill him.”

In the narrative offered by witnesses like Brantley, it was Encina and not Marquise who presented the greatest danger that night. Or, as Washington puts it, “What if you and your family had been across the street? Sitting inside that suburban that got hit with two bullets? We don’t even know where most of his (Encina’s) bullets ended up.”

It’s unclear why police never took a statement from Brantley, in particular, especially if Encina himself approached him after the shooting. However, it appears Brantley might want little to do with the case now. In his recorded conversation last year with the DA’s investigator, he says he works in Houston during the week and warns them he won’t show up for any grand jury hearing on a weekday.

In court this past January, Segovia and Norton testified that the DA’s office subpoenaed Brantley to appear before what would have been a second grand jury in the Marquise Jones case last year. As promised, Brantley was a no-show. Washington questions why the DA’s office didn’t file a warrant that would have forced him to show up. “If they wanted his testimony, they would’ve gotten it,” he said.

The DA’s office declined comment when we asked why they didn’t continue to pursue Brantley for a second grand jury hearing, especially after the damning comments he’d already given to one of their own investigators.

Remarkably, Brantley’s name still appears on the trial witness list Washington filed in court last week. Lawyers for Encina and the City of San Antonio are asking for a judge to stop him from testifying, arguing they’ve tried to depose him several times ahead of trial but that he keeps dodging service. In their court filing, they argue Brantley’s testimony at trial would be an “unfair surprise.”

Considering his statements to the DA’s investigator last year, it seems pretty clear what he’d say in court.

“He (Jones) pulled his pants up and he (Encina) shot the shit out of him,” he told the investigator. “He shot him up.”

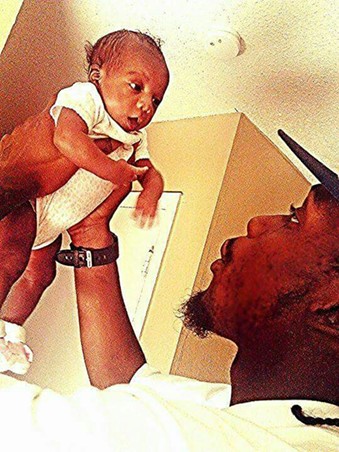

Deborah Jones Bush knows her nephew had a rap sheet before he died, but she insists his outlook on life started to change six months before he was killed, when his daughter Kaelynne was born. She says he cut his braids to, as she put it, “look more presentable.” He’d started taking classes at Northwest Vista College and was searching for a steady job to support his new family.

The morning of Marquise Jones' death, Bush got a call from her sister saying their nephew had been shot. When she got to the Chacho’s parking lot, sometime around 7 a.m., his body was still on the ground, under a tarp. She says she had to say goodbye to him from behind police tape.

To her, the fact that the case has even made it to trial is a sign from God. “We believe in God, we believe that’s why it’s gone this far,” she told the Current. “We’re a spiritual family.”

Bush also says she’s not surprised it was Encina who killed her nephew. Two weeks before the shooting, on Valentine’s Day, she claims that Jones and his uncle “got into it” with Encina outside Chacho’s – the family lives nearby. She says they’d lost their car keys and were looking to see if they’d dropped them in the parking lot. “He showed up and accused them of trying to break into cars,” she says.

The morning Jones was shot, Encina shouldn’t have even been working at Chacho’s. The officer hadn’t been authorized to work off-duty jobs. It’s unclear if that’s because of an incident at another restaurant three years prior that almost got him fired.

SAPD disciplinary records state that one night in April 2010, Encina was drunk at Mama Margie’s, a Northwest Side restaurant where he sometimes worked security, when he started harassing workers and antagonizing black customers. He kept going into the kitchen, even when workers asked him to stop. “Where are my fucking tacos?” he demanded at one point. One worker said he touched her inappropriately (in a deposition, Encina would later say he only touched her “in a playful manner”). “Look at that pussy-ass bitch,” he told one group of customers, before throwing his food and declaring himself a “baller” from the East Side. Records indicate his friends had to “bear hug” him and force him outside.

Records show SAPD considered firing Encina. Instead he agreed to a 45-day suspension, not that he actually missed any work. As allowed under the city’s contract with the local police union, Encina gave up vacation and holiday time instead.

Along with that disciplinary case, the attorney for the Jones family also points out that the year before Encina shot and killed Jones, he was involved in another questionable death at the hands of San Antonio cops. He’s one of eight SAPD officers named as defendants in a lawsuit filed by the surviving family of Jesse Aguirre, whose April 2013 death on the side of a San Antonio highway was caught on camera.

As the lawsuit describes it, officers cuffed Aguirre’s hands behind his back and flipped him over the highway barricade directly onto his head. They then lifted him up, pushed him facedown against the hood of a patrol car, and then again brought him to the ground. “The officers bent his legs back towards his body and one officer sat on his legs,” according to the lawsuit. “Yet another officer used an open hand to press Mr. Aguirre’s head against the ground. … While Mr. Aguirre was on the ground he made numerous cries for help and pleaded he could not breathe.” Aguirre’s body went limp while the officers were still piled on top of him. The lawsuit alleges they waited several minutes before trying to resuscitate him, at which point it was too late.

Police officials have blamed Aguirre’s death on a mix of cocaine and alcohol that led to “excited delirium.” Attorneys for the family cite two medical expert reports that conclude he was likely suffocated. The lawsuit is still pending.

On the morning of February 2014, Whitney, Marquise Jones' sister, says she didn't hear Encina yell any warnings at her brother before the gunfire started. She was forced to stay inside the car after the shooting. Once other officers arrived on scene, they detained her in the back of a police cruiser until they could take her to the station for a statement. They also seized her cell phone, meaning family wouldn’t learn for several more hours that her brother lay dead in the parking lot.

One officer testified in a court deposition that Whitney was crying, shaking and even started to kick at the window inside the police cruiser after enough time had passed. In her affidavit, Whitney says it was because, for more than an hour, she’d been “forced to sit in a car where I could see my brother’s motionless body on the ground.”

[email protected]