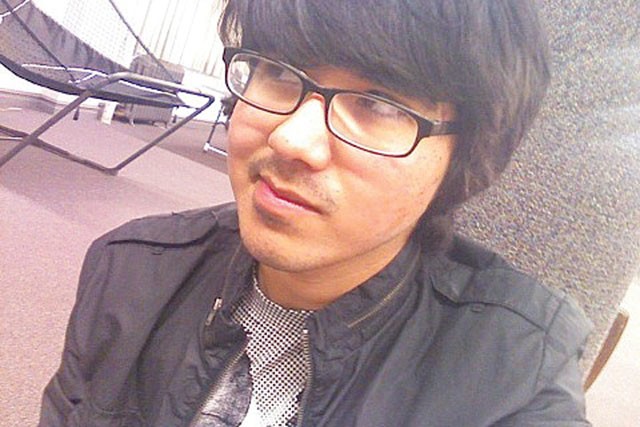

The queer subculture that exists within San Antonio and other heavily concentrated Latino communities maintains itself despite cultural stigmas associated with being gay. The strong sense of familia that penetrates the core of queer Latino life among friends and allies, however, does not always diffuse the inner conflict we grapple with because our sexuality collides with the sexual roles that are traditionally dictated by our culture. Danny Olvera, co-founder of xQsí Magazine, an LGBTQ Latino multimedia publication that reexamines identity, recently took some time to talk with the Current about being a queer man in the traditionally male-dominated and thoroughly religious Latino community.

What was your personal coming-out experience like? Were you immediately accepted by your family?

Coming out was very hard for me. It took a lot of inner reflection and two suicide attempts before I was able accept myself for who I am. But in reality, it’s actually a continuous process. Everyday you come out a little more; everyday you learn more about who you are in relation to the rest of the world. It has taken me years to get where I am today, but now I can honestly say that I am proud to be a queer Latino.

The men, ironically, took it in stride, while the women refused to listen. My mom particularly, who is devoutly Catholic, has yet to accept me for who I am. At first, this rejection caused me a lot of stress and lost sleep. I love my mom. I used to do her eyebrows and zip up her dresses. I’d watch her get ready for church or cook in the kitchen. We had always been very close. But then, when I came out, it all changed. Suddenly, all those small moments took on a certain meaning to her. I think that’s what scares her. She’s afraid that it’s her “fault” that I’m queer, although I know it’s the reverse. I did all those things because I was a femme little boy. I would have been femme and queer even if she would have pushed me out to help my dad in the garage.

Our relationship has since improved. I realized that if I want my mom to accept me, I need to accept her. It took me 20 years to accept myself as queer. It's incredibly selfish to expect her to assimilate in a shorter time frame.

What are your thoughts on gay/queer culture within the Latino community? What sort of progress have we made?

Queer culture has always been a part of Latino culture. How can you talk about Oaxaca and not touch on las muxhés, a group of third gender, transwomen who have been an integral part of the Zapotec community since before the arrival of the Spaniards? How can you talk about the rise of indigenismo in Mexico without mentioning Frida Kahlo, whose bisexuality is key to understanding her work as a visual artist? But similarly, Latinos have been a part of U.S. queer culture. Sylvia Rivera, a transwoman of Venezuelan and Puerto Rican heritage, threw the first bottle at cops that fateful night at the Stonewall Inn. Danny Sotomayor, a Mexican-Puerto Rican, was the first nationally syndicated, openly gay political cartoonist in the country. So the question hasn’t been whether we as queer have been within the Latino community or we as Latino have been within the U.S. queer community, it’s why have we been systematically erased?

Luckily for us, all that is hidden comes to light. And that’s the progress we have made. We now refuse to be erased. We are in a process of, as queer Chicana Cherríe Moraga said, re-membering our past, re-attaching it to our collective history. As the Latino community in the U.S. grows, so does the queer Latino community. It is now that we can begin to bridge both our identities, as Latino and queer.

What can we do to change or strengthen the dynamic of queer life within Latino skin? Do you consider the queer community a minority within a minority?

We have to start telling our stories, all while being cognizant of what stories aren’t being told. I think right now is the perfect time. I mean, there’s a queer Latina former cheerleader on Glee and a lesbian sub-plot in the Mexican telenovela Las Aparicio, for Tonanztín’s sake! We shouldn’t have to wait for more. We should be the ones creating these stories. And what’s so exciting is that we are! There are a few projects I am really excited about, one of them is this film that just recently secured funding from Kickstarter called Mosquita y Mari, and another is a documentary by my friend Jonathan Menendez called Gay Latino Los Angeles. But there are lots of other ways our stories are being told, besides film. My friend Bamby Salcedo founded Angels of Change, a space for transgender youth, and every year releases a high fashion calendar to empower these young women, most of whom are Latinas. So one way or another, our stories are being told. Our job, therefore, is also to support these storytellers.

How has your view of queer Latinidad influenced your work at xQsí Magazine?

Once I came out, I realized how desperately I wanted to see myself reflected in the media. And it is this realization that drives me to do the work I do for xQsí. I know there are countless queer Latino youth out there who are growing up ashamed of being Latino and queer. I was one of those youths. Hell, there are adults out there ashamed of being queer and Latino; either they deny the importance of their heritage or deny the relevance of their sexual and gender identities.

If I can help another queer Latino embrace his or her culture and sexual/gender identity, then I know I have done my job. Queer Latinidad begins once we have left the shadows behind, step forward and scream with pride” “I am a queer Latino, �y qué?”

Christine Garza blogs for the Current as Contemporary Xicana at blogs.sacurrent.com. Also, check out xQsí Magazine at xqsimagazine.com.