Luis Jiménez’s Man on Fire fuses the god Prometheus, whose myth inspired the Mexican muralists, with Cuauhtémoc, the last Aztec emperor whose fire torture at the hands of Spanish conquistadors became legendary.

Despite his work’s reputation for inflaming community passions, Jiménez has become one of the McNay’s most-collected contemporary Texas artists. In celebration of the installation of the 7-foot-tall burnt-red Man on Fire bronze sculpture on the Brown Foundation Sculpture Terrace, the McNay Art Museum presents “Native Son: Prints and Drawings by LuisA. Jiménez.”

While the Man on Fire image can be traced to Jose Clemente Orozco’s Man in Flames—painted in the late 1930s at the former Hospicio Cabañas in Guadalajara, Mexico—the sculpture was born during the tumultuous 1960s when Buddhist monks were immolating themselves to protest the Vietnam War.

But Man on Fire is a prescient self-portrait as well. Jiménez struggled to bridge the New York contemporary art world and his own Mexican-American heritage as the son of an El Paso sign painter. Tragically, he died in 2006 in his studio in Hondo, N.M., when a large section of a monumental sculpture the 65-year-old artist was molding for the Denver International Airport, Blue Mustang, fell on his leg and severed an artery.

Like most of Jiménez’s large public sculptures, Blue Mustang, a 32-foot-tall, 9,000-pound blue-fiberglass rearing wild horse with blazing red eyes, has stirred controversy. Jiménez’s staff and family completed the sculpture in 2008, only to be met with demands it be removed from the airport site after people dubbed it “Bluecifer” and “Satan’s Stallion.” Denver decided to give the Blue Mustang five years before citizens could petition for its removal, but so far in 2013, it’s still standing. Purchased by the city for $650,000, Blue Mustang is now appraised at $2 million.

Jiménez’s sculpture has been controversial in San Antonio, too. Installed nearly 20 years ago as a loan to the University of Texas at San Antonio, Crossing the Border, a father carrying his son on his shoulders across the Rio Grande, has been condemned by conservatives for “glorifying illegal immigration,” but it’s still on view overlooking the Sombrilla Plaza at the 1604 campus. However, Fiesta Dancers, commissioned by UTSA in 1996 for the University Center, is a beloved landmark.

As per its title, this show focuses on the artist’s two-dimensional works, although in some cases there are direct links back to his sculptural endeavors. From the collection of Harriett and Ricardo Romo, Fiesta (Diptych) (1985), could be a study for the UTSA sculpture, depicting a dancing couple with the man wearing a rainbow-colored serape and the woman a green, gold and red dress. Also from the Romos is the shiver-inducing Sidewinder (1988), a fork-tongued snake in rippling blue and orange. Both works are lithographs accented with glitter.

In his drawings, Jiménez unites the flowing, swirling lines of the Mexican muralists and their concerns for the human condition with Chicano rasquachismo, which debunks convention and spoofs conformity. Drawing on hot rod cartoons and romanticized Mexican calendar art, Jiménez merged pop art with the primarily Latin American 1960s movement known as New Figuration, which rejected the utopian premises of modernism to probe the corruption of contemporary society.

Nowhere is Jiménez’s existential despair more evident than in his series of prints inspired by the Day of the Dead. A wobbly man is propped up by a prostitute and skeletal woman in Entre la Puta y Muerte (Between the Whore and Death). A grinning skeleton batters a man to the ground in La Lucha (The Struggle). Like one of the four horsemen of the apocalypse, Death rides an angry steed in A Veces a Trote, A Veces a Galope (At Times a Trot, At Times at a Gallop).

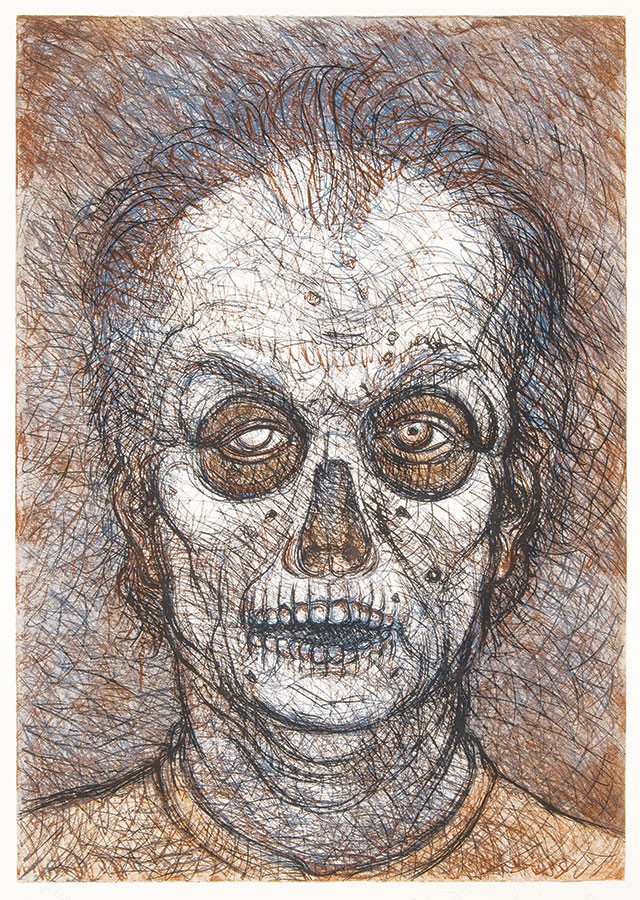

In his Self-Portrait (1996), Jiménez’s face is so thin-skinned you can see his skull underneath. His hair is thinning into spidery lines, he has one dead eye and he’s lost his nose. But the most haunting image is the final screenprint he worked on at Austin’s Coronado Studio, which shows a screaming woman running from the fires of hell.

Wrestling his demons, Jiménez merged his North American and Mexicano experiences to forge a new way of seeing the border region that shaped him, creating a fiery body of work to outlast la muerte, which finally overtook him doing what he loved best.

Native Son: Prints and Drawing by Luis A. Jiménez Jr.

$10-$15; free for members and from 4-9pm Thu

10am-4pm Wed, Fri; 10am-9pm Thu; 10am-5pm Sat; Noon-5pmSun

McNay Art Museum

6000 N New Braunfels

(210) 824-5368

mcnayart.org

Through Jan 19