Last December, I did something that made the majority of my friends question my sanity—I moved from Austin to San Antonio. They wanted to know why I would do such an absurd thing as leave the “hippest city on Earth.” I could answer them in one word: traffic. In a recent study done by INRIX Inc., Austin surpassed New York as the city with the fourth-worst traffic in the United States. What use is it to have world-class restaurants, museums and events if you can never get to them?

I wanted to be connected to a culturally rich, vibrant community. San Antonio, with its SA2020 goals and city-center rebirth, seemed the place to be. So, I sold my Austin home and bought a small historic cottage in San Antonio on a street that, little did I know, was about to make headline news. My boyfriend and I now live on South Main Avenue just one block from H-E-B’s headquarters.

You have likely already heard that H-E-B has requested the block of South Main that runs from César E. Chávez to Arsenal in exchange for building a downtown grocery store. When I first heard about this plan last spring, I wasn’t that worried. The Mayor and City Council, after all, would never consider shutting down a major downtown thoroughfare just as the Decade of Downtown was taking off, would they? That thought just goes to show how much I had yet to learn about San Antonio politics. Heywood Sanders, a professor of public administration at University of Texas at San Antonio’s College of Public Policy, was quick to bring me up to speed. “San Antonio does not plan: We do deals,” he explained to me.

When it became clear that the City might very well hand over public property—something that you and I all own a piece of—to a corporation so that they can wall it off, I was stunned. And I wasn’t the only one. My next-door neighbor, Naomi Shihab Nye, an internationally renowned poet and author, has lived on South Main for over 34 years. “I was sickened!” she said, “I felt like, ‘God, this is so wrong.’”

Almost every single one of my other neighbors felt the same way, so we banded together to form a grassroots organization called Main Access (mainaccess.org) and started a petition to keep South Main Avenue open. Our membership has grown to include citizens from every district in San Antonio.

Brief History of South Main Avenue

In order to understand why so many people would be so upset about a street closure, let’s start with a little history lesson. Back in 1947, traffic conditions had grown so bad in San Antonio that a group of citizens called the South Side Residents started a petition to open up Main Avenue through the former U.S. Arsenal property. The street was finally opened in 1949.

In the 1980s, H-E-B purchased the Arsenal property and turned it into their headquarters. According to Todd Piland, H-E-B’s executive vice president of real estate and facilities, H-E-B has been intending to take over the street since they first relocated to the area.

In May of 2011 and possibly even before that, H-E-B held private talks with the City concerning the building of a downtown grocery store and the closure of South Main Avenue. A downtown grocery store had been needed since 2008 when H-E-B shut down two stores on the South Side. As a result of the 2011 talks, the Express-News reported that city officials at the City Manager’s office jumped the gun and sent out canvassing letters regarding the street closures to all potentially affected entities. When H-E-B protested, the City had to apologize to the company and recall the letters.

Then, the City announced that it was offering a $1 million dollar incentive for a downtown grocery store. Four companies submitted plans to the city, with H-E-B’s being announced as the winning proposal on August 30, 2013. H-E-B’s proposal came with a catch, though. In exchange for building the store, they wanted a street.

At a Coffee with the Councilman event, District 1 Councilman Diego Bernal explained his take on H-E-B’s proposal, saying, “I believe that H-E-B thought that because the City wants a grocery store so badly—and obviously we do if we’re willing to give somebody $1 million to do it—that since H-E-B wanted to close the street anyway, it would be a good time to tie the two together. They may have even gotten some advice from city staffers that this was a good idea.”

Why Does H-E-B Want Main Avenue?

All this begs the question of why H-E-B wants this street so badly. I asked this question to Piland and he gave me three reasons.

First, H-E-B is concerned about the safety of their employees crossing South Main. According to Piland, none of their employees have ever been in an accident crossing the street, but one employee did get bumped by a car several years ago. In addition, he says there have been several near-misses.

As a resident of Main Avenue who crosses the street multiple times daily, I can vouch that you do have to be careful when crossing the street at certain times of the day. That’s the nature of living downtown on a major thoroughfare. Speed bumps, stop signs and other traffic-control devices could be added to alleviate this issue.

The second reason Piland gave me involves campus security. In another meeting with H-E-B, Dya Campos, the company’s director of governmental and public affairs, explained that H-E-B has in the past received terroristic threats. I can certainly believe that. As a writer of textbooks that discuss evolution, I have received several terroristic threats myself. So have all the publishers I’ve ever worked for. My boyfriend, James Rodriguez, is a lawyer and says that the courthouse receives multiple threats every month. This is the current state of affairs in this country. We cannot shut down streets next to every organization that receives a threat. We’d have no streets left.

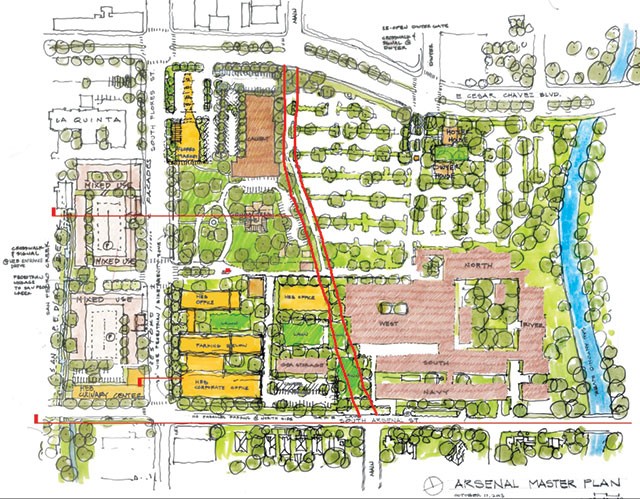

The final reason Piland gave me for needing to close the street is that their company is growing and needs the space. To me, this is their most serious argument. When looking at their recently revealed master plan for their campus, I saw several indications that H-E-B already has a great deal of space to grow into. First, they are planning on covering half of the requested segment of South Main in green space, which sounds lovely, I will admit, but this green space will be walled off from the public.

The second half of the street will be covered in surface parking. It is important to note that the Lone Star Community Plan adopted by the City in March of this year designated H-E-B’s property as being underutilized because the structures were worth less than the land itself. The primary reason for this designation was the large amount of surface parking already on H-E-B’s campus, which is not a good use of land in a dense urban core.

So, according to the plan, H-E-B needs the street to add around 10-20 parking spaces to their campus. Interestingly, they own, but do not use, the parking lot on the northeast corner of the intersection of S. Main and César E. Chávez. They also own, but lease out, the parking lot across from Amols’ Specialty Inc. at Flores and Arsenal Streets. According to their master plan, H-E-B has no intention of building on these lots in the foreseeable future.

In addition, when I asked Piland about the mixed-use developments shown on the plan along the block of Flores Street that H-E-B wants to develop in exchange for closing Main, he explained to me that they have no set ideas yet about what will go there. He added that they likely won’t start any kind of project there until long after he retires. Furthermore, two of the properties—512 and 516 S. Flores St.—are currently under litigation at the probate court. This litigation calls into question H-E-B’s title to this property. So, that leaves three city blocks that we know of that are already in bad condition and will be left to continue to deteriorate over time.

There is a common, but highly unethical, practice in real-estate in which a developer purchases lots of land and lets them deteriorate. This causes the property around the land to also decrease in value, making it easier to purchase adjacent lots when they go on sale. In this way, a developer can accumulate large parcels of land at lower than market value. I am not accusing H-E-B of doing this, but I think we should all question why a company that owns so much undeveloped land around its campus is insisting it needs a public street in order to grow.

The Drama Unfolds

In September, the City canvassed several of the entities that would be affected by the closure of South Main. One of the entities canvassed was the King William Association, which responded to the canvassing by opposing the closure. Three different KWA insiders have privately confirmed that H-E-B has now postponed a meeting with Zet Baer, KWA Fair Coordinator, concerning H-E-B’s financial support and infrastructure enhancements they traditionally donate to the Fiesta event.

Other entities have also opposed the closure, including the Conservation Society. In addition, several city departments, including the Parks and Recreation Department, opposed the closure during the internal canvassing process. However, after separate open records requests seeking the results of the canvassing were filed two weeks ago by Main Access and KWA, the CCDO reached out to all non-consenting departments, thanked them for submitting their first drafts, and asked them to re-respond to the canvassing request.

I asked Sanders why the City would be so determined to allow H-E-B to close Main Avenue. “It started out as developers saying people don’t want to live downtown because there is no convenient grocery store,” Sanders explained. “The Mayor staked out the notion that a grocery store would be a magic silver bullet [see pp. 13] to transform downtown’s prospects for residential development. He’ll do what it takes to make this deal happen.”

Economic Consequences of Closing a Street

However, not everybody is convinced that a grocery store will solve downtown’s development woes. H-E-B has recently announced a $100 million dollar development plan to sweeten the deal. (Note: The Express-News reported H-E-B is no longer asking for the $1 million incentive. According to Piland, this is not accurate. H-E-B is interested instead in reinvesting the $1 million into a public works project.) H-E-B is also talking about bringing jobs to the area.

Piland explained that 1,600 workers currently in other office buildings north of downtown would be consolidated into the downtown campus. Then, of course, jobs would be created by the store and gas station they intend to build in the area. In addition, as H-E-B grows as a company they will presumably be adding jobs. Bernal admitted in the Coffee with the Councilman session that he is not totally clear on just how many jobs H-E-B was talking about.

County Commissioner Kevin Wolff doesn’t think any incentive, including the street, should be given to H-E-B without the City Council being given hard numbers around jobs. “We get asked for incentives all the time,” he says. “We have a lot of really good criteria in regards to those incentives: How many new jobs? How much do the jobs pay? All of these types of things. If somebody came to me and asked me for $1 million for an incentive and told me that they were going to employ a maximum of 15-20 people at minimum wage, I’d say ‘Hell no.’ Of course, the real incentive H-E-B is going after is not that $1 million; it is the street.”

One thing I don’t think City Council or H-E-B has considered yet is the impact streets have on jobs. H-E-B is talking about adding 1,600 more people to their downtown campus. If South Main is closed, how will this affect traffic on Flores and César E. Chávez? If a store is also at that intersection, won’t this create even a worse traffic problem? Traffic can substantially affect a company’s growth. For example, a study by the Airport Corridor Transportation Association reports that 30 percent of Pittsburgh employers claim commuting issues were the number one barrier to hiring and retaining qualified workers.

On the other hand, complete streets stimulate the economy. The National Complete Streets Coalition reports, for example, that improvements in the street grid in the Capitol Hill district of Washington, D.C. helped lead to the opening of 44 new businesses and 200 new jobs. In addition, sales for businesses in the improved area have more than tripled.

A high level of walkability also improves the economy. Walkability refers to how easy and safe it is for a pedestrian to move around an area. High walk scores are correlated with a decrease in crime, a decrease in obesity and an increase in property value. In fact, according to a study done by George Washington University School of Business, increasing a Washington area’s walk score by six points directly led to a 67 percent increase in the area’s economic performance.

According to WalkScore.com, San Antonio’s current walk score is 40.8, which is the lowest walk score of any other U.S. city that is close to San Antonio’s size. This walk score indicates it is hard to get around the city if you don’t have a car. The walk score for my section of South Main, on the other hand, is currently 77—highly walkable.

Closing down a block of South Main Avenue will significantly lower this walk score. The economic damage that will be done by decreasing this walk score will not be immediately obvious to city council members when they go to vote on this issue. It’s not a number that can be readily calculated. But it is telling that many relevant current City plans and documents point out the importance of Main Avenue and complete streets in general. Streets such as South Main Avenue with its sidewalks and bike lanes are critical to the City’s urban revitalization plans.

Now, in order to get that magic “silver bullet”—a downtown grocery store—the City appears to be willing to violate or alter the objectives of the Lone Star Community Plan, Major Thoroughfare Plan, Transportation Plan and more. Closing South Main is also counter to the mayor’s SA2020 goals for a healthier, more accessible, pedestrian- and bicyclist-friendly downtown.

“I think the grid is a really critical issue here—keeping the grid open and alive and breathing,” says Nye. Interestingly, Piland inadvertently agreed with her, saying at a meeting that took place three days later, “There may be a need for two downtown stores: one in the north part of downtown and one in the south part of downtown, because it’s not easy to go from south to north through downtown.”

Exactly, Mr. Piland. Let’s do what we can as a city to try to improve the situation, not make it worse. Let’s keep South Main Avenue open—open to citizens, open to growth, open to the future.