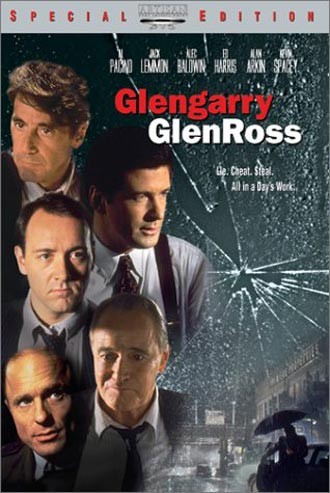

In Glengarry, there are only a half dozen irate males, but each one does the work of a handful, distilling the sadder attributes of the modern American man and bringing them to individualized life. These guys are salesmen, as we all are, and they show us every stage of the corporate life cycle: from Kevin Spacey’s toe-the-line rookie mentality, to can’t-lose Al Pacino, whose winning streak has convinced him he’s the king of the world (or is it the other way around?), to Jack Lemmon, a man who has had his day and will never have another, no matter how desperately he begs for it.

James Foley traps his characters in dim-lit rooms, hemming them in with a constant rainfall outside the door, persistent commuter trains rattling the windows, and neon lights bleeding through the cracks in the walls. The leads — the suckers who just might buy property from these losers — are all out there, in their two-story bungalows on the other end of the phone, cozy and not especially eager to let men in damp overcoats come in for coffee. Mamet provides just enough plot to get his men talking, then sits back and listens; this is a rare Mamet film, in which the actors are forceful enough to bend the man’s dialogue to their own purposes, but nimble enough not to break it.

Mamet’s world may be stylized, but a look at the Maysles brothers’ Salesman (Criterion Collection) shows just how close it is to real life. In what many consider the birth of the feature-length non-fiction film, Albert and David Maysles follow a team of door-to-door Bible salesmen as they try to unload ornate, coffee-table-sized editions of the Good Book on folks who really can’t afford them. These men are as suited to metaphor as those in Glengarry, but the filmmakers won’t reduce them to that, filming them instead with an empathetic eye; it’s a strategy — refusing the cheap laugh or cynical observation in favor of humanizing quirky subjects — that has always characterized Maysles films, and makes this doc a perfect complement to the Mamet/Foley film.

If the dynamics between these salesmen are easy to see as representative of the larger male world, then Jim Jarmusch’s Down By Law (Criterion Collection) goes the other way, taking three men in a homogenizing environment — jail — and making them completely unique. It would be hard to do otherwise with this cast: Tom Waits, Roberto Benigni, and Stranger Than Paradise vet John Lurie are about as idiosyncratic as they come, with personalities that push and pull at each other but still belong in the same world, a black-and-white, run-down place somewhere between the cracks of our own.

Anybody who recoiled at Benigni’s “I’m so cute” routine at the Oscars a few years back will enjoy watching him be abused by Lurie’s character, who has little patience for the Life Is Beautiful star’s pidgin English; Lurie’s also a nice foil for Waits, whose low-energy hipster disc jockey is so clueless he seems destined to return to jail as soon as the trio (who escape from a chain gang into the swamps of Louisiana) get back to the semi-civilized world.

Down By Law is, like Stranger Than Paradise, a skewed take on the road movie genre, and in Lurie, Jarmusch had an ideal dry-witted stand-in for himself, looking at America through the eyes of a Lower East Side-dwelling European immigrant. The musician/actor may have recently returned to playing a convict (in HBO’s Oz), but it would sure be nice to see him back in front of Jarmusch’s camera, the kind of hustler more likely to come in the side window than the front door, more likely to be selling a stolen car radio than a faux-leather-bound Bible.