Forty-four years after their first hit, the Isley Brothers re-emerge as patriarchal pop stars

It has often been said that Madonna and David Bowie are pop music's greatest chameleons, its supreme masters of reinvention.

Of course, what passes for reinvention in pop music tends to be about as deep as a change in hair color, a new fashion

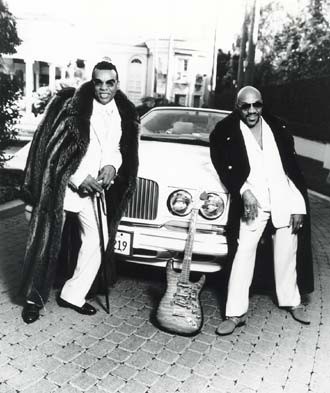

| Ronald Isley and Ernie Isley |

Bowie has been more adventurous, but even his work has tended to vacillate between his folk-rock roots, the avant-garde electronica he absorbed from Brian Eno, and the Limey soul of records like Young Americans and Let's Dance.

If you throw out image and focus on music, a much more deserving candidate for pop's ultimate chameleon would be the Isley Brothers. Over the last 45 years, they have repeatedly emerged as a new group, adapting to shifting trends without ever completely losing their essence. Most recently, with the aid of R. Kelly, they have recast themselves as R&B's gangsta elder statesmen, spiritual heirs to the Blaxploitation tough-guy tradition of Dolomite and Superfly. And, in one of modern pop's unlikelist twists, they are more popular than ever, with their latest album - the Kelly-produced Body Kiss - debuting last week at number one on the Billboard Top 200.

Among other things, the album's early success confirms that child-porn and pedophilia allegations haven't yet soured the public on Kelly. His creative vision dominates on Body Kiss, as he gives Ronald and Ernie Isley taut, sensual grooves that sound like some reimagined version of Curtis Mayfield's early '70s classics. He also gives the group a touch of the Santana-comeback treatment, pitting Ronald Isley's gritty tenor against Lil' Kim in the title song, with Jill Scott in the infidelity dialogue "Busted," and with Snoop Dogg in "I Like."

What really drives the Isleys' latest round of popularity is Ronald Isley's alter-ego, Mr. Biggs. Isley, as Mr. Biggs, has gone head-to-head with Kelly in a series of videos, establishing a patriarchal OG persona for himself, with his flashy suits, fur coats, bowler hats, and gold-tipped walking sticks. It is noteworthy that the album is credited to "The Isley Brothers featuring Ronald Isley aka Mr. Biggs." For more than four decades, Isley has been one of the great soul singers on the planet. Now, in his early 60s, he has inexplicably emerged as a pop-culture phenomenon.

The good part about all this is that it has provided a hook for a band that has always been easier to listen to than define. In their first incarnation, with the driving, 1959 secular-gospel chant "Shout," the Isleys were roughhouse R&B, revved-up doo-wop in the mode of Hank Ballard and Jackie Wilson. In the early to mid-'60s (defined by their endlessly covered hit "Twist and Shout"), they were chitlin-circuit rock 'n' rollers, featuring an explosive young guitarist named Jimi Hendrix in their road band.

During the mid-to-late '60s, they settled into the Motown stable, softening their edges with lush pop like "This Old Heart of Mine" and "I Hear a Symphony." Leaving Hitsville in frustration at the end of the '60s - Motown chief Berry Gordy responded by suing them - the Isleys expanded from a trio to a sextet, and let their freak flags fly. Drawing on both R&B's tough new funk, and the fuzz-tone heroics of their former sideman Hendrix (although Ernie Isley credits Jose Feliciano as a bigger influence on his six-string style), they created a body of work that perfectly captured the socially conscious mood of black pop in the pre-disco '70s.

The Isleys were tougher and quirkier than most of their peers from this era. Fourteen years before Public Enemy galvanized the hip-hop world with the expression, the Isleys insisted: "We've got to fight the powers that be." Flying in the face of media stereotypes about lazy, unmotivated black men, the Isleys delivered "Work to Do," an unsentimental portrait of a man struggling to meet his responsibilities. Even the majestic anthem "Harvest for the World" is more impatient than optimistic, excoriating America's systemic hypocrisies and questioning when the have-nots will have their day.

In the early '80s, the Isleys, much like black pop, swung toward slick, love ballads, before splintering for several years. The current lineup features only Ronald and Ernie, and is built primarily on the still-considerable power of Ronald's voice. In fact, if there's a problem with Body Kiss, it's that it feels like a Ronald Isley solo album, as written by R. Kelly.

While Kelly gives Isley some inspired material - catching Jill Scott in a series of lies in "Busted," and seeking revenge in "Showdown" - the album suffers from a few too many of Kelly's by-now-patented Hallmark-card love songs. But Ronald Isley long ago proved he could transcend all manner of musical fluff. This is the guy, after all, who once took Seals and Crofts' "Summer Breeze" and made it sound like a soul classic. They don't call him Mr. Biggs for nothing. •