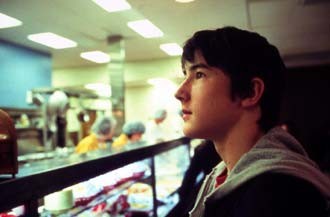

| Alex Frost plays the lead in Gus Van Sant's Elephant. (courtesy photo) |

Two connotations of the title Elephant, both via the film's writer/director Gus Van Sant: The title is borrowed from a 1989 Alan Clarke film about killings in Northern Ireland; Clarke thought of the events as "the elephant in the living room that no one could mention." It also refers to the old joke about a group of blind men trying by touch to describe an elephant in front of them; one thinks it's a wall, one thinks it's a rope, one thinks it's a tree, and so on.

In response to events such as the Columbine massacre, Van Sant suggests, those who look for simple reasons are like the blind men: One thinks video games are to blame, one demonizes violent movies, one thinks the killers should have gotten involved in organized sports. For his part, Van Sant lets the questions present themselves. Instead of trying to answer them, he spends a mostly quiet, entirely sad hour-and-a-half in its presence.

Not a dramatization of Columbine per se, Elephant imagines a very similar horror, this one also perpetrated by two male students in a typical middle-class high school, and focuses on the day leading up to it. The cast, as in some of the director's earlier films, is made up of non-actors who, in many cases, essentially play themselves. With Van Sant's encouragement, they are impressively natural in front of the camera. Some critics have suggested that the director's gaze is overwhelmed by the beautiful faces in it, but that's off-base: Larry Clark's movies about kids frequently leer at them sexually under the guise of intimacy while Van Sant would rather know his subjects than exploit or consume them.

While one gets the distinct impression that Elephant originates in that kind of close cooperation, the film itself simply observes. Harris Savides' camera glides through polished halls ceaselessly, in long Steadicam shots that often do nothing but follow behind someone. The process emphasizes the psychological detachment of each student from his surroundings. We see people speaking with each other, but by and large, these kids live in their own heads. It's a different view from the traditional high school film, in which cliques of friends are the norm, but many viewers will agree it gets at just as much truth.

That detachment is emphasized by the movie's approach to chronology. As he focuses on one individual, Van Sant lets that person's experience override a collective linear timeline; we spend time with one character, then cut back to meet another. Occasionally, the forward rush of time is slowed suddenly, so that we linger in a moment before moving on; the film is manipulated in such a way that the slow-motion isn't always obvious when it begins.

The film's non-linear movement isn't obvious at first, either. Two opposite impulses pull at each other: the suspense motive, in which jumps back in time are used to agitate the viewer, building up anticipation of the violence to come; and empathy, which views each character as more important than any narrative requirements. Van Sant tends toward the latter, as demonstrated largely by his choices of music - rather than have a dramatic score highlight repeated moments or churn up tension, he plays Beethoven - but the weight of the event we know is coming makes a certain nauseating anxiety inevitable, especially after the point where we first see the killers, dressed in camouflage and carrying duffel bags, head toward the school's doors.

| Elephant Dir. & writ. Gus Van Sant; feat. Alex Frost, Eric Deulen, John Robinson, Elias McConnell, Kristen Hicks, Matt Malloy, Timothy Bottoms (R) |

We are never given a hint of what motivates the two boys to do what they do. Rather than seeing them sit at home and seethe with anger at jocks and stuck-up girls, we see them watching television and eating breakfast. When they do eventually go over their plan, one says to the other, "most importantly - have fun, man." We are offered the heartbreaking randomness of the murders: The first girl killed is a plain, awkward kid who we have seen was just as much a victim of high school's cruel insistence on conformity as her killers. And while we are shocked with the boys' easy access to weapons - point-and-click, sign for the package the next day - that availability seems incidental to the crime.

In the end, Van Sant points his camera at the elephant. He doesn't know what he's looking at - and he wants to let you know that you don't, either - but he knows that it has crushed something very beautiful. The film he leaves behind is a haunting meditation on questions we probably can never answer. •

As of press time, Elephant did not have a firm opening date scheduled in San Antonio. The film, however, is already screening in Austin theaters.