|

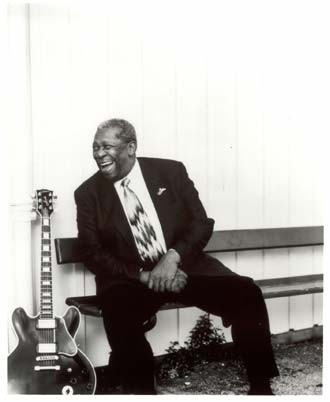

B.B. King can't stop paying the cost to be the boss B.B. King turned 79 last week, but he didn't do a whole lot of celebrating. "I rode all the way from Los Angeles to where I am `Phoenix`," King says, with only the slightest hint of droll sarcasm. "That was it. I live in Las Vegas, but I didn't even go through home." That's the way it's gone for King since he burst onto the blues circuit in 1951 with his sultry recording of "Three O' Clock Blues." He's lived most of his adult life on the road, maintaining an average of 300 shows a year for decades. Now, despite his advanced age and the onset of diabetes, he still plays about 200, with no intent to slow down. As King himself once wrote, in an infamously sexist blues classic, he can't stop paying the cost to be the boss. "As long as my health is good and people come to my concerts, still buy my records, and I can handle myself well, I don't see no reason to stop," he says. "I can't fish every day. I like old Westerns, but I get tired of them sometimes. So there's nothing else I care to do." A native of Itta Bena, Mississippi, King migrated to Memphis, the musical hub of the mid-South, in 1947 and landed a job as a disc jockey for WDIA, the nation's first black-operated radio station. Every day, King, then known as "Beale Street Blues Boy," would spin records for an hour and play live on the air for 15 minutes. Even at that stage, he demonstrated unusually catholic tastes for a Delta bluesman. "I was allowed to spin anything I wanted to, there wasn't as much politics in it as there is today," he says. "I played everything from Bing Crosby to Lightnin' Hopkins, with the exception of myself. I never could play my own records.

King's eagerness to be the international goodwill ambassador of blues, to take his musical genre from Mississippi juke joints to Las Vegas casinos, has been a mixed blessing for his reputation. On one hand, it's made him synonymous with the blues, a transcendent figure recognized by people who wouldn't know T-Bone Walker from T-Bone Burnett. On the other hand, it's also made his career look like a triumph of marketing more than music. Purists tend to grumble about the slickness of King's recorded catalog, his use of horns and strings, and his mercenary inclination to sing for any fast-food giant that offers him a pile of cash. While it's true that King never approached - or aspired to - the hellraising depths of a Howlin' Wolf, a listen to any of his work leading up to 1965's historic Live at the Regal album would dispute the notion that his music has been tame. A listen to his feisty early sides also reminds you what a scoundrel he could be, as in the self-written "Beautician Blues," when he gushed about all the fine women he was able to meet at his girlfriend's hair salon. King's guitar playing has been a miraculous example of his ability to turn his technical limitations into assets. Unlike most guitarists, who start by mastering basic chords before graduating to soloing, King learned in reverse: playing single-note lead parts until he became a masterful soloist, but never becoming a functioning rhythm guitarist. In fact, one of King's defining performance traits is to neglect his guitar while singing (often pounding his right fist into his left hand to emphasize the vocal line), and to follow a vocal with a brief guitar figure that seems to provide a response. "Always, whenever it was time for a solo, they said, 'Go ahead B., you've got it, get it,'" he recalls. "So I would concentrate on how to highlight the band when I go out front. `U2's` Edge plays them chords so beautifully, he's a whole rhythm section by himself. I can't do that, but I can, if you give it to me, I'll take it around."

By the late '60s, King had built a sizable white following, but his true pop-culture breakthrough came in 1970 with "The Thrill Is Gone," a lush, soulful, midtempo number that was his lone Top 20 hit and a sort of unofficial signature song for him ever since. It's a measure of King's humility that the most famous bluesman of all time says about radio: "Had they treated all of my records as they did that one, I would probably be a star myself." King says of the record, "It was my first so-called pop hit, but I never did change what I was doing." In fact, though, he did adjust to the song's success, making a series of records (e.g., the Stevie Wonder-penned "To Know You Is To Love You") that shared more with Motown and Philly International than with anything cranked out by Chess Records. Ultimately, King is like Ray Charles or Louis Armstrong, legends whose musical personalities were so strong they could find the R&B in country or the jazz in pop. In King's hands, Leon Russell's "Hummingbird" feels like a blues song, although it's undeniably a middle-of-the-road pop ballad. Also like Charles and Armstrong, King has been a long-distance runner constitutionally driven to keep gigging until his body gives out. But he admits he's paid a price for his work ethic. "I've been married twice and divorced twice," he says. "That's been the hardest. But it's been my life now for about 57 years, so I don't know hardly anything else." •

|