|

'Long Dark Road' fails to illuminate the motives behind Robert Byrd's murder By the end of Long Dark Road: Bill King and Murder in Jasper, Texas, University of Texas psychologist and psychoanalyst Ricardo Ainslie seems to have thrown up his hands. Ainslie spends the prior 250 pages ruminating over the troubling aspects of a June night in 1998 when the 28-year-old King, Russell Brewer, and Shawn Berry murdered James Byrd Jr, the troubled son of a well-respected black family, dragging his body naked behind Berry's pickup truck and finally leaving it in front of an African-American church. King and Brewer were sentenced to death and now reside on Texas' death row; Berry received a life sentence. "... I, too, did not want to believe that relatively ordinary people could commit such brutal acts," Ainslie writes. "... it means that, given the right alchemy, perhaps anyone might become capable of monstrous cruelty." But Ainslie doesn't focus on the "anyone" in this case: Shawn Berry, unlike Brewer and King, had no prior history of incarceration at the brutal, race-segregated Beto I penitentiary. The book instead revolves elliptically around the charismatic King, with whom the author seems to have become so emotionally involved that he can't step back and give us the benefit of his professional background. Ainslie accedes to King's desire to remain an enigma. He presents King as a man who has been mishandled by family and society, an exceptionally bright, engaging boy who somehow went astray, but while he spends a great deal of time revisiting King's difficult childhood (he discovered as a teenager that he was adopted by his step-grandparents, who spoiled him but could not erase the feelings of abandonment), for a psychologist he is strangely dismissive of King's bipolar diagnosis and evidence that King has Antisocial Personality Disorder or is a sociopath. "He also seems incapable of feeling remorse," he notes near the end of the book, "although I have never quite relinquished the idea that perhaps ... he has simply managed to convince himself of his innocence." These, and other traits Ainslie describes, are associated with APD (which the American Psychiatric Association estimates afflicts 4 percent of the general population, and sociopathy, which occurs at an estimated rate of 3 percent). It seems odd, to say the least, that Ainslie wouldn't discuss these possibilities without an explanation - except that it would undermine his conceit that we are all only a few steps away from Bill King. Borrowing an insight from the preternaturally perceptive George Eliot, that we all act on "fatal metaphors," Ainslie prefers to make King's flaws literary and therefore beyond solution.

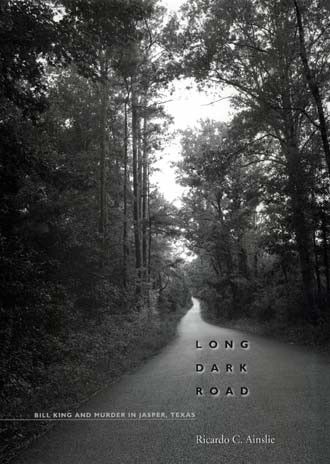

There are many but-fors in Bill King's life: if he had been able to reconcile with his birth mother, if he had found Jesus or a competent psychiatrist in Beto I instead of the Confederate Knights of America, if he had received regular medication for his bipolar disorder ... But Ainslie never constructs these disparate tragedies into a compelling argument for how we might prevent another Bill King. We are left instead with an ominous warning with little insight (other than the "we all might be capable" that is explored more potently via the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda). King is the most abhorrent of the three perpetrators and, despite his claims of innocence, most likely the ring leader in Byrd's murder. Yet, James Byrd might still be alive today had the forceful King not had accomplices. In failing to consider Shawn Berry, whose involvement was surprising to even Byrd's family whereas King's surprised no one, Ainslie fails to explore how 1990s East Texas differs from 1920s East Texas and how, most importantly, natural leaders with evil intentions bring ordinary followers along with them. Therein lies the answer to whether each of us has the potential to be complicit on another long dark road. • By Elaine Wolff

|