Michael Antonioni’s ’70s masterpiece proves some things really change

In the dark shadows of Quentin Tarantino and Guy Ritchie, Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1975 quasi-thriller The Passenger glows faintly. Or maybe the problem is the tag studios and reviewers stick on the film. The first time I rented the original version, it was to watch a “riveting” performance by the young, “magnetic” Jack Nicholson, starring as a disillusioned reporter who swaps identities with an international arms dealer. And he is magnetic to a degree, but if prime Jack is what you’re after, he gives a more gripping psychological portrait in 1970’s Five Easy Pieces as a classical pianist who hides from his demons in the Texas oil fields.

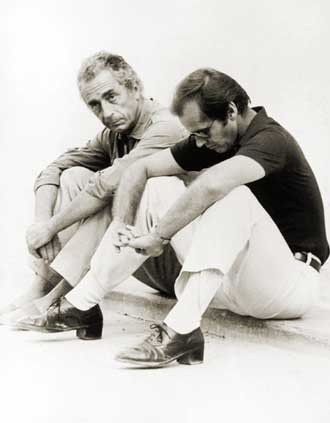

| Director Michelangelo Antonioni sits with Jack Nicholson, who stars as journalist David Locke in The Passenger. |

Synopses also tend to play up The Passenger’s story line, implying that there’s a “showdown” with the gun-runner’s nemeses at film’s end. But the showdown that does take place is of the quiet-desperation variety. Before his sudden death by heart attack, the arms dealer tells Nicholson’s character, David Locke, that he is a globe-trotter, and every place is the same. Not so, says Locke. Every place is new and different; we make them the same by forcing them to fit our preconceived notions and habits. A doomed attempt to outrun the self follows, and like most lams, what begins with giddy optimism ends in frustration as the past closes in. The film might have been called Cul-de-sac, had Roman Polanski not used the title in 1966.

What’s most interesting about The Passenger, which is receiving a theatrical re-release as a “director’s cut” this month, is how it contrasts with contemporary society, in filmmaking technique and zeitgeist. Antonioni’s frames, constructed in modified thirds, are frequently breathtaking, and the film’s slow pacing gives the viewer plenty of time to behold them. No flashy editing, jump cuts, or music camouflage lame dialogue, weak acting, or sloppy shots. The movie asks, and expects, a viewer’s patience with a confidence that seems unthinkable nowadays. (The director also squeezes in a couple of those over-the-top ’70s cheesecake shots, here with the boyishly sexy Maria Schneider in a Madonna-like pose.) The Passenger’s one gimmick, the end-of-reel frames that punctuate the movie numerous times, is a pacing tool that also reminds us how little Locke actually understood the stories he documented on film.

| The Passenger Dir. Michelangelo Antonioni; writ. Antonioni, Mark Peploe, Peter Wollen; feat. Jack Nicholson, Maria Schneider, Jenny Runacre, Ian Hendry, Chuck Mulvehill (PG-13) |

Remade by an American movie studio in 2005, The Passenger would likely focus more on the African civil war that lurks in the backstory. In Antonioni’s version, it seems unlikely that Locke, a seasoned journalist, could be oblivious to the dangers of his new identity, but he carries on like a spoiled actor in an unsatisfactory role. The first rebel contact he makes thanks him for being a gun-runner who cares about the cause. But even though real engagement is what Locke—who was frustrated by his outsider status when he was covering the conflict as a reporter—seeks, he fails to understand the import of this conversation. It’s a crucial mistake that leads to his downfall, but we never learn more than Locke does about his contacts.

This refusal to use a third-world conflict to lecture first-world movie viewers (it assumes some critical thinking skills, which I’ll admit is optimistic) is pleasurably anachronistic here, but what may strike 20-somethings as even stranger is the story arc: In the age of Donald Trump, we all know that redemption is only a makeover and a mantra away. •

By Elaine Wolff