With the complete La Perdida newly published in novel form, Jessica Abel looks for the next adventure

Jessica Abel’s Brooklyn brownstone looks pretty much like I imagined it would, with its original wood moldings and heavy old cabinets full of books and records — the home of 30-something former indie-hipsters who’ve traded in bar-hopping for gardening and nesting.

Abel looks the way I’d pictured her, too, those oversize reddish glasses and short brown hair familiar from drawings in her popular comic Artbabe and from her self-portrait at the back of her latest graphic novel, La Perdida.

Abel started Artbabe on a lark in 1992 when she pulled some strips together to show the publishers of Fantagraphics at the Comic-Con in her native Chicago. Fantagraphics didn’t immediately bite, so Abel self-published whenever she could find time between day jobs. Influenced by the likes of Love and Rockets and dominated by clever glam-rock chicks wrangling with angsty romantic entanglements or hanging out with girlfriends in grungy bars, Artbabe became a hot underground comic at a moment when few other women were drawing them. Most female cartoonists of the time exuded a confessional vibe, so readers figured Artbabe was autobiographical, too, instinctive outpourings rather than well-crafted stories.

“I assume that happened partly because I’m female,” she shrugs as she darts into the kitchen to check something simmering on the stove. “I’ve always been seen to have a talent for developing characters and if they feel real, people think they must be real,” she says. “When La Perdida was first serialized `in 2001`, everyone assumed it was autobiographical, but as it went along people figured out Carla wasn’t me — or hoped it wasn’t me, given what happens in the book.”

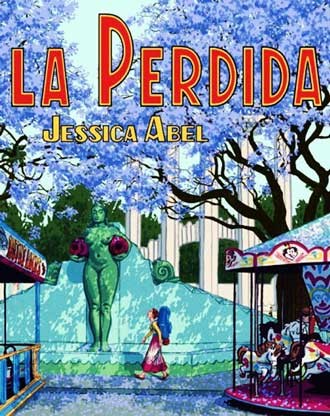

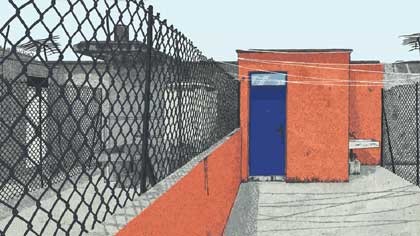

| La Perdida, a five-part serialized graphic novel by Jessica Abel, has been collected in a new volume from Pantheon. The story follows the misadventures of a 20-something expat searching for meaning and identity south of the border. The rainy plaza scene, above, and the starker image at right, became the backdrops for issues Number Two and Four in Fantagraphics’ original serial, available at Fantagraphics.com. Original prints can be purchased through the artist’s website, Jessicaabel.com. |

An American naïf adrift in Mexico City, Carla gets in trouble while ostensibly searching for her Latina roots. A self-described “crunchy ethnic wannabe” with a serious Frida Kahlo complex, she earnestly sets out to differentiate herself from her expat friends, including her rich ex-boyfriend Harry who doesn’t know any locals (except “the guy at the liquor store”). Carla, on the other hand, befriends a gang of Mexican Marxists who constantly tease her about American imperialism and her desire to go native. “I’m not a conquistadora!” she wails at one point, shredding her beloved Frida poster and smashing one of her folkloric pots. Its shards take up a whole white page, a visual emblem of Carla’s confusion.

Abel herself ended up in Mexico in 1998 on a romantic whim. She’d been turned down for a grant and so decided to accompany then-boyfriend and fellow cartoonist Matt Madden (now her husband) on his move to Mexico. A year later she started work on a comic about expats that morphed into La Perdida. “I wanted to create a portrait of Mexico City — and then I set terrible crimes there!” she says with a rueful laugh. “It is rough and magical, and if you’re an idiot or really unlucky, you can get in really big trouble there, a lot bigger and a lot more easily than in New York.” Carla does get caught up in some serious peril, but Abel doesn’t make excuses for her clueless heroine. “Carla acts dumb, and I love characters who are blind in one way or another. I never write characters who have it all together — why bother?”

| “It is rough and magical, and if you’re an idiot or really unlucky, you can get in really big trouble there, a lot bigger and a lot more easily than in New York.” – Jessica Abel |

Carla’s a recognizable type, the pious American trekker in search of something authentic. But she’s not a stand-in for all Americans, as becomes clear when her brother Rod shows up for a visit. A laid-back skateboarder, Rod seems to know way more interesting people and places in Mexico City than Carla. He takes her to raves and introduces her to Mexican hipsters — the equivalent of the characters who populated Artbabe, and more like the kind of people Abel says she hung out with during her stint abroad. But Carla veers away from this cosmopolitan milieu because, as Abel explains, “She doesn’t feel different or interesting enough at home and when she goes with Rod to parties, she feels like as much of a dork as she did `back in Chicago`. She wants to become somebody new when she goes away.” But Carla’s too wrapped up in her romanticized images of Mexico to see danger approaching, even as a stark noir edge creeps into the book’s later panels.

Abel spent years doing comic journalism for alt-weeklies like Chicago’s New City, sketching entertaining reports on Godzilla conventions and Camille Paglia lectures. Although she’s not interested in serious reportage, Abel wouldn’t mind if the fictional La Perdida got roped into the successful subgenre of graphic novels that deal in foreign affairs and war zones. “In mainstream society, sitting around reading `Joe Sacco’s` Safe Area Gorazde, nobody’s going to look at you like a goofball. It’s obviously serious stuff.” She mentions a recent afternoon on which she settled down for a solo lunch at a chic Manhattan restaurant with a glass of wine and ... the latest issue of Superman. “People were walking by and just looking at me,” she says with a chuckle, whereas “if you were sitting there reading something like `Marjane Satrapi’s` Persepolis, people would be like, ‘Hmmm, interesting, I read about that in The New York Times.’”

A teacher at the School of Visual Arts, Abel is now working on a comics textbook with Madden (whose most recent book is 99 Ways to Tell a Story). “He thinks a lot about formal structure and relating to poetic forms,” she says, “and I think about narrative structure, novelistic ideas like narrative arcs. That’s always been a concern, but without an education, I wasn’t able to formulate it, and it was so frustrating.”

The red parlor grows dark all of a sudden as a delicate wave of rain hits the bay windows. A female SVA student has arrived for a critique session — Abel estimates the gender ratio in her class is now 30 to 40 percent female. “My age and above, I could count the active female cartoonists on one hand. But there are a ton of young women starting now,” she says exuberantly, chalking it up to the popularity of manga and the independent comics boom of the ’80s and ’90s. (She leaves unspoken her influence on newcomers.)

Abel is also exultant about the New York comics scene, which she dove into six years ago. “A large part of my brain is devoted to organizational activity,” she quips, and during their first year in New York, she and Madden launched a popular discussion series called Comics Decode. Days after 9-11, the duo also kick-started an impromptu event called SP-Xiles: “We sent out e-mails to everybody and made flyers and said anybody who had comics could come for free and put down a blanket and sell them, and we raised money for disaster relief.” It was “a love-in” — one that partly inspired the creation of the annual Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art Festival, now an NYC staple.

Even as a fairly successful cartoonist, Abel’s not sure she can make a good adult living from it. (Almost five years passed between the beginning of the first issue of La Perdida and Pantheon’s publication of the graphic-novel collection.) And she’s also not certain what direction to take. “The Artbabe characters mostly tracked my age — they were all in a transitional stage where life hadn’t come together for them yet.” With La Perdida, she returned to that fluxed-up 20-something mindset. “I do want to write about people my age, but the problem with my life is I’m happy. I’m married, I have a house. I’m in pretty good balance. That’s what I need to imagine: What would it take to knock me off?” •