Sketches of Frank Gehry holds true to its name

“That is so stupid-looking it’s great.” In that single sentence, uttered as he and an assistant are contemplating a crude model they’ve been tinkering with, celebrity architect Frank Gehry captures something of the spirit of his work that this film about him sometimes tries too hard to prove: You don’t need a dozen talking heads and architectural historians to convey the unpretentious fun to be had in seeing a Frank Gehry building for the first time. If the building in question happens to be 10 inches high and made of crumpled notebook paper, so much the better.

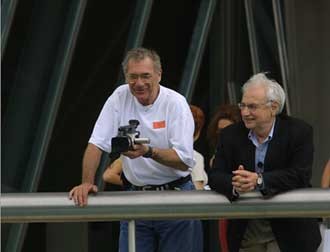

| Sydney Pollack (left) and Frank Gehry in Bilbao, Spain. |

Sketches of Frank Gehry, as the title suggests, is a little like one of those taped-together paper forms Gehry uses to tease his ideas into three-dimensional life. It’s not definitive in any respect; it’s loose and amiable, but viewers wanting a lot of solid information may find its approach lazy.

The film’s intimacy derives from Gehry’s decades-long friendship with Sydney Pollack, the actor and filmmaker who here tries his hand at a documentary for the first time. (One imagines the friendship being forged when Gehry was struggling and Pollack — whose ’70s and ’80s hits include The Way We Were and Tootsie — was a bigwig. These days, with Pollack struggling to eke out a good feature, the roles are reversed.) Pollack, video camera in hand, hangs out in the architect’s studio and wanders with him through some of his famous buildings. His role fluctuates: Sometimes he’s an old buddy shedding light on Gehry’s pre-fame struggles; sometimes he’s a well-intentioned dilletante trying to understand the architect’s methods. The conversation takes a revealing turn when the men find common ground, discussing the plight they share as creative people who, unlike painters or poets, must balance inspiration against commercial considerations. (Unacknowledged in this talk is the fact that Pollack has always been an extremely commercial filmmaker, who has never had to sell corporate financiers an idea anywhere near as avant-garde as one of Gehry’s buildings.)

Pollack visits with a celebrity-heavy array of Gehry’s admirers, many of whom appear a bit too eager to convince us that they “get” him. Obscenely wealthy Hollywood types like Michaels Eisner and Ovitz talk about what a genius he is (subtext: “I’m a genius for commissioning that building”), while once-fashionable painter (and not-bad filmmaker) Julian Schnabel, obnoxiously, insists on being interviewed in his bathrobe. More productive comments come from artist Ed Ruscha, who has known Gehry since early on and offers more insight than attitude.

The praise-fest is interrupted only rarely, by critic Hal Foster. Foster voices understandable concerns about the “starchitect” phenomenon, suggesting that in some cases Gehry’s buildings are so aggressively out-there that they fail to meet their tenants’ or the public’s needs. The film nods politely, admitting that maybe the Guggenheim Bilbao isn’t the most suitable space for some works of art, and moves on. It has another expert on hand, former New York Times critic Herbert Muschamp, to bury Foster’s misgivings with praise.

If the movie doesn’t do as much as we’d want to transmit the sensual pleasure of Gehry’s buildings (despite its flaws, the sometimes transcendent My Architect was much more successful on this count), it does a good job of exploring the mind that created them. Gehry himself comes across as unpretentious and open, uninterested in mythologizing himself. He’s especially interesting when talking of the point at which he rejected cookie-cutter assignments and followed his muse. Expanding the narrative is his therapist from the time, Dr. Milton Wexler, who encouraged Gehry to jettison anything holding him back (including his first wife).

One of the doc’s weaknesses is a dearth of information about how Gehry’s whimsical, physics-defying buildings are made to work in the real world. We see how computers have enabled his firm to translate models into two-dimensional, contractor-friendly drawings, but the movie could really use a couple of detailed looks at how enormous weight is supported and oddly shaped rooms are kept from falling apart.

That kind of education will have to come from another filmmaker. Sydney Pollack is in a privileged position to make these Sketches, but he isn’t interested in fleshing out the finished portrait.