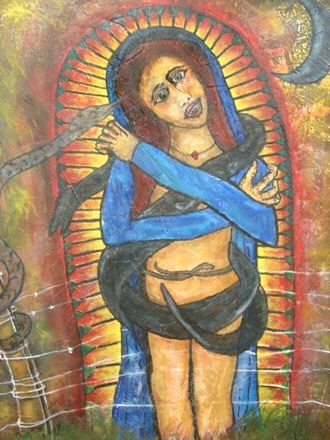

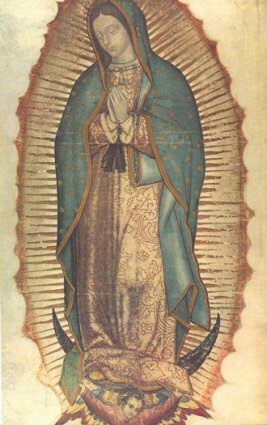

| Two ways to view the Virgen de Guadalupe: Anna-Marie Lopez’s “Virgin,” left, draws on an Aztec deity. At right is a 16th-Century painting. | |

Centro Cultural Aztlan’s light-filled Galeria Expresión is hung with images of the Guadalupana for the annual Celebracion a la Virgen de Guadalupe. But for all the variety of materials — mixed media, expressionist and folk-art painting, and ceramics — there’s little creativity in the subject matter. When she’s not portrayed in her traditional robe, mantle, and rays, she’s an attractive woman, humanized, feminine, humble, and motherly. In a 21st century that has arrived despite genocide, endless warfare, slavery, and revolution, it feels like something’s missing.

And maybe it is. Anna-Marie Lopez says that her large painting of the Virgen as an aspect of the pre-Columbian Aztec goddess Tonantzin was pulled from the show at the last minute — after she had been told it was accepted and after Centro called and asked her the price for the gallery tag.

Lopez’s “Virgin” is a marked departure from the images that are displayed in the gallery: naked except for a blue mantle and a strategically placed serpent, she wears a human heart on a strand around her neck and stands behind a barbed-wire fence. “I thought it would be interesting to take it back to the original,” says Lopez, who researched the Virgen’s origins when lead artist and curator Anel Flores invited her to submit work for the show. “I was very serious about doing this right and a little more in-depth.”

From the moment she first appeared in 1531 to the Indian Juan Diego on a Mexican hillside to request a shrine, the Virgen de Guadalupe was a personal intermediary for the indigenous and mestizo populations of the Americas, a saint of the people, not of the powerful. She graced the insurgents’ banners in Mexico’s War of Independence from Spain and more recently represented the Zapatistas. She’s no less prevalent in Mexico’s former backyard, San Antonio, where she is easily recognized by her hallowed accessories: a radiating aura that has been interpreted as cactus spines as well as rays, a moon beneath her feet, and a mantle draped over her bowed head.

But the relative consistency with which the Guadalupana is portrayed belies her not-so-secret history. Catholic friars have wrung their hands for centuries, concerned that when Mexicans worship the Virgen, they’re showing at least equal devotion to Tonantzin, her Aztec predecessor. The Lady appeared a mere decade after the Spaniards took Tenochtitlan, and according to numerous scholars the spot she chose for her shrine was previously occupied by a popular temple to Tonantzin, who was also associated with the moon.

So clear are the associations between Guadalupe and Tonantzin, that the debate isn’t “if” but “how”: Did the Mexican Indians adopt the Virgen as a way to covertly worship their own gods? Or did the Church once again repurpose the pagan deities of its new subjects to speed up the conversion process? Other scholars, including the philosopher Roger Bartra, have suggested that the Guadalupana’s mestiza identity (and her early 16th-century incarnation) ties her to the mother of modern Mexicans, La Malinche, the controversial indigenous woman who aided and eventually had a son — symbolically the first mestizo — with Hernán Cortés.

This last observation begins an article in the Fall 2006 issue of El Aviso that Denise Cadena, Arts Program Manager at Centro, and Excecutive Director Malena Gonzalez-Cid gave me when I visited Centro last week. The article talks about post-modern reinterpretations of the Virgen and their power to fight oppression, especially of women; but it also notes that there is strong resistance from religious conservatives who are accustomed to using the Virgen to promote their moral codes.

Gonzalez-Cid says Lopez’s work wasn’t censored; it simply wasn’t selected. Censorship is something that happens after the fact, she says, once art is on display and public outcry causes it to be taken down. Yet Gonzalez-Cid admits that she believes San Antonio has a certain expectation about this show — which originated with the brothers at St. Mary’s University — that Centro needs to meet. “When a community sets a standard, it’s gonna be a pretty high mark for the Virgen de Guadalupe in this town. I’m going to support that standard,” she says. “I know that in the artistic community, she’s an icon. In this community she’s first a religious icon.”

In fact, Celebracion includes portraits of the Virgen titled “Tonan” and “Tonantzin” (the latter by longtime Centro program director Ramon Vasquez y Sanchez), but their subjects are clothed in traditional Biblical garb and any rebellious symbols are as artfully embedded as they might have been 500 years ago.

Flores says she selected Lopez’s painting and was under the impression it would appear in the show until four days before the opening, when she was informed by Centro that it would not be included. “I regret that she wasn’t in the show,” says Flores. “I stressed to them that there are Chicana women writers that have been writing about these different interpretations of the Virgen.”

Lopez says that she tried to demonstrate respect for the Catholic tradition by covering up the full-frontal nudity of her original and removing some of the more ferociously pagan symbols, such as the hands and feet that hung next to the heart around her Virgen’s neck, but it’s important to her to acknowledge Mexico’s rich cultural and religious heritage. “It’s not just the traditional folk-art Catholicism,” says Lopez of the Guadalupana. “It’s richer than that.”