Three years ago, Scott Kimble, a chiropractor and cattle rancher, was among the first of Karnes County residents to lease his mineral rights when landmen came calling for acreage above the Eagle Ford Shale, a geological formation rich in oil and gas 10,000 feet beneath a vast stretch of South Texas.

After observing the oil and gas industry’s sizable water demands for hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” Kimble’s third eye for business spotted an opportunity. He now sells millions of gallons of water to the industry, earning 10 to 20 cents per barrel. The Eagle Ford has since become one of North America’s hottest petroleum plays. But in water-scarce South Texas, a lucrative spin-off business has begun in water sales. Some landowners earn 40 to 80 cents per barrel of water along with their $3,000 to $8,000 per acre for oil and gas rights.

Pennies per water barrel might seem a pittance compared to $90 crude oil prices, but they add up to plenty of fat checks when each oil or gas well requires at least 71,400 barrels (3 million gallons) of water to be fracked.

“Yeah, it’s lucrative,” Kimble said of selling water. “There’s no up-front cost and a very minimal contract.”

That easy money is made possible, in large part, by Texas’ rule of capture, which grants rural landowners unfettered access to whatever water is available from the ground for oil and gas drilling — even if that use results in pumping a water table dry, which is exactly what Kimble saw happen last year on parts of his land and at other Karnes County properties.

“There are some legitimate examples where it took 90 days” for a well to be pumped dry, Kimble said. “Yes, it concerns us.”

Kimble’s foray into water wildcatting taps into many of the issues facing water conservation in South Texas, and it may be a sign of what’s to come. An even bigger water fight is brewing as the perfect storm of a projected Texas population explosion meets the realities of global warming. In the coming 40 years, the state’s population is expected to double, while the Rio Grande Valley may see growth on an order of 175 percent, according to state forecasts. Meanwhile, federal and international research indicates the future of South Texas and beyond will be a considerably drier place, with average temperatures expected to rise by at least 6 degrees this century.

While local government agencies have explored strategies to prepare for suburban sprawl over the next 50 years, there are still concerns the state is doing little to regulate the oil and gas industry’s use of water, even as conflicts between urban and rural interests over the wet stuff are growing.

“Climate change will probably exacerbate water supply issues,” John Nielsen-Gammon, state climatologist and Texas A&M University professor, told the Current. “We definitely have seen temperature increases, and that causes more evaporation, which causes more crops and lawns needing water and less water recharged into aquifers.”

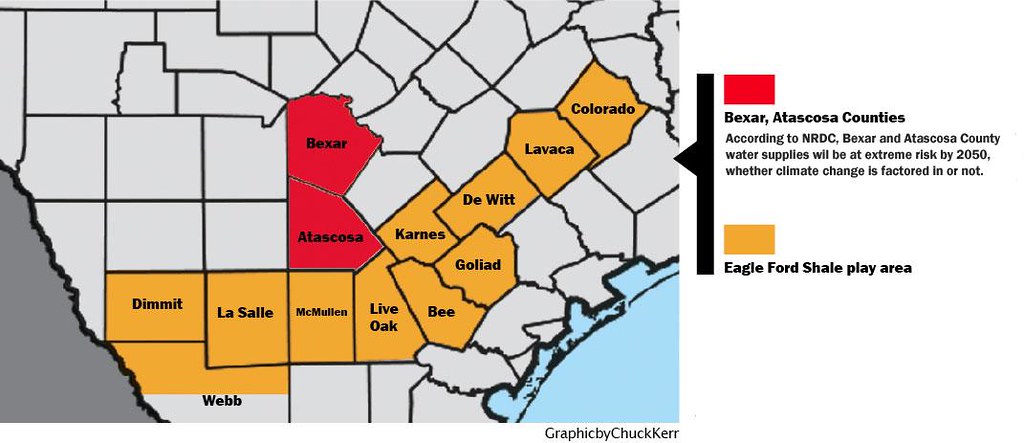

A July 2010 National Resources Development Council report predicts Texas will be among states most affected by climate change where “renewable water supply will be lower than withdrawal, therefore increasing the number of areas vulnerable to future water shortages.”

Groundwater

The NRDC also noted that borrowing water from neighboring counties or basins won’t remain sustainable as more localities compete for the same resources. The San Antonio Water System (SAWS) has already invested millions in reducing its reliance on the heavily regulated Edwards Aquifer by pumping water from neighboring counties — much to the consternation of rural users. SAWS plans to build and operate a desalination plant by 2016 to pump and desalinate millions of gallons of brackish water from the Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer at the southern tip of Bexar County near the Wilson and Atascosa county lines.

Rural South Texans already bracing for the full impact of SAWS’ water hunting on the Carrizo-Wilcox, Sparta, and Queen City aquifer levels are now being forced to turn their attention to the oil and gas boom in the Eagle Ford. On January 5, the Current reported that the region’s Evergreen Underground Water Conservation District began monitoring water wells after South Texas landowners complained that water tables in the shallow “water sands” were rapidly sinking as the oil and gas industry pumped millions of gallons of water for hydraulic fracking.

Oil and gas industry spokespeople contacted for this story haven’t said whether or not their companies have also noticed water levels impacted by fracking operations. “We are not in a position to address the level of detail contained in the questions you submitted,” K Leonard, a spokesperson for EOG Resources said via e-mail.

Darrell T. Brownlow, a South Texas rancher and former Evergreen board member appointed by Governor Rick Perry, said in a recent Texas Ground Water Association newsletter that economic impact of the Eagle Ford boom would far outweigh the water concerns. He estimated that 20,000 oil and gas wells fracked over 10 to 15 years would use about 300,000 acre feet from the Carrizo – the equivalent of a single year’s worth of all current regional users.

“It’s not that significant,” Brownlow, who is also vice president of CEMEX USA, said last Thursday during a presentation to the San Antonio Petroleum Club. “If we have a problem with that, there’s still a $100 billion benefit for the region.”

Still, even Brownlow, who also works with the oil and gas industry on his properties in the Eagle Ford and in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale, thinks there could be a better system for monitoring water use.

“My legislative recommendation … is something that would require the Railroad Commission to log wells and provide better information to groundwater districts,” he said.

After some of the sudden well drops in Karnes County, the oil and gas industry began drilling deeper to the Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer, South Texas’ main water source, Kimble said. Brownlow said Karnes County and the eastern parts of the play face short-term water issues because they are closer to the shallow Gulf Aquifer. He predicts that the areas farther south, particularly in and around LaSalle County, will become central to supplying the entire Eagle Ford play with water via trucks and pipelines.

There has been talk of water recycling plants and pumping more brackish water from sections of the more plentiful Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer, but the industry prefers fresh water because the chemicals used in fracking don’t mix well with heavy salt concentrations. Brackish groundwater, once considered worthless, can now potentially provide potable water via desalination plants like the planned SAWS facility. Unsurprisingly, SAWS is also paying close attention to the Eagle Ford boom and hydraulic fracking’s potential to contaminate water sources. “The water used in fracking is not subject to any regulation by groundwater districts and, as far as I know, they don’t take it into account for desired future conditions,” said SAWS spokesperson Greg Flores. “With regards to availability, that’s a pretty big issue and something I would like `to monitor`.”

Add to these challenges weak state regulations, an omnipresent oil and gas lobby, and the industry’s dirty reputation for contaminating drinking water supplies around the country with methane and a variety of toxic drilling chemicals used in the fracking process. This unruly cluster of concerns may only unravel with divine intervention, or perhaps, though less likely, some serious action by the Legislature, now entering its 82nd session.

Ironically, SAWS’ plan to pump from the Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer is a sort of end-run around the state’s regulations for large municipal water users. Cities in Karnes, Wilson, Frio, and Atascosa counties face pumping limits from the Evergreen Underground Water Conservation District similar to the way SAWS water use is capped by the Edwards Aquifer Authority. However, there are no limits for pumping from the Carrizo-Wilcox in Bexar County because there is no water conservation district for that small area.

Broken regulation

While South Texas communities have not yet experienced the widespread fracking-related contamination of water wells and aquifers that has become evident in other parts of the nation (see "Sinking feelings," January 5, 2011), activists say it’s only a matter of time. “Why would any rational person think `the industry` won’t do the same things in Eagle Ford?” asked Sharon Wilson, a North Texas activist who documents contamination complaints of North Texas wells on her blog.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in December ordered Range Resources Corporation to take action to protect North Texas residences in Parker County, where some water wells were contaminated with methane by fracking. The U.S. Justice Department stepped in last week by filing a complaint to force the Fort Worth-area company to address the contaminated wells.

The oil and gas industry is regulated by the Railroad Commission of Texas, but the EPA Regional Administrator Al Armendariz said he was compelled to step in on the Parker County case because the state agency failed to act.

Wilson is among many environmentalists who grouse that the Railroad Commission of Texas, Texas Water Development Board, and Texas Commission on Environmental Quality are so flawed and corrupt that industry interests regularly trump environmental concerns about air quality and water conservation. Such decades-old complaints were affirmed by a scathing Sunset Report last year that found that the RRC does not deter the oil and gas industry from environmental violations because it rarely cites violators or issues fines.

The report called for major restructuring of the RRC, including more inspectors, and greater budget reliance on fees and permits from the oil and gas industry to address encroachment of fracture drilling near the Eagle Ford Shale in South Texas and Barnett Shale in North Texas. “As the oil and gas industry continues to affect significantly populated areas of the state, the Commission needs an enforcement process that leaves little room for the public to question the agency’s appropriate and consistent handling of identified violations,” the report says.

The Sunset Review process also reamed the TWDB, calling out a lack of coordination among statewide water planning efforts and the TWDB’s lack of data that would enable informed conservation decisions. The report doesn’t even address the fact that the oil and gas industry — which is pumping untold billions of gallons of water across Texas — is not subject to water restrictions or reporting requirements.

“The Sunset process showed there’s a big problem of enforcement of existing rules as well as the adequacy of current statutes and rules,” said Craig Adair, spokesman for Rep. Lon Burnam, D-Fort Worth. Burnam is among a handful of legislators working on fracking-related legislation, including a proposed law that would require the oil and gas industry to disclose the chemicals it combines with water used in the fracking process.

Under the dome

Texas employs more oil and gas workers (1.77 million) than Oklahoma, Louisiana, California, New York, and Pennsylvania combined, according to a 2009 report by PricewaterhouseCoopers. The big story at the start of the 82nd Legislature is whether Texas’ $27 billion budget shortfall has proved New York Times economist Paul Krugman right. He argued that the Wall Street Journal and other conservative voices got it wrong when they celebrated Texas’ pro-business, anti-regulation economy as a success story immune from the budget woes that had befallen liberal states like California.

Addressing the Sunset Reviews would be a tall order for the Legislature in the best of economic times, so most progressive lawmakers see no chance for serious consideration of restructuring the Railroad Commission or implementing major recommendations.

“I wish I could say something optimistic, but given the political attitude in the Legislature and its laissez-faire perspective (on regulation) I’m not real optimistic,” Burnam said.

A spokesman for freshman state Rep. Jose Aliseda, R-Beeville, said the legislator’s office has talked to the Evergreen district and other constituents about water concerns, but there are no plans for water or fracking-related legislation.

A pending lawsuit before the Texas Supreme Court cuts to the heart of rural property owners’ rights to capture water from restricted aquifers, although it does not appear to address the exemption for oil and gas drilling. Landowners hope a decision in favor of a Von Ormy farmer whose water was limited by the Edwards Aquifer Authority will solidify their rights. Water districts fear such a decision would further weaken their ability to regulate.

The Texas Water Development Board concluded that just three percent of North Texas groundwater near the Barnett Shale was used for fracturing. Though the Bureau of Economic Geology is working on nailing down the numbers for the Eagle Ford, one obvious contrast is that in South Texas (barring a recent application for water from the San Antonio River near Karnes) nearly 100 percent of fracking water comes from groundwater.

“Yes, there is an impact of water usage by an oil field, but it’s not anything near as much as what people make it to be when you compare other uses of water,” said Rich Varela, senior vice president of the Texas Independent Producers and Royalty Owners Association.

Alan Dutton, an associate professor of hydrogeology and aqueous geochemistry at the University of Texas at San Antonio, said the oil and gas industry might want to consider reimbursing landowners who have to lower pumps. SAWS has a mitigation program to reimburse landowners when water tables go down from pumping in Gonzales County. “The Eagle Ford will probably be a classic boom and bust that lasts about 10 years,” Dutton said. “Gradually, water wells in the aquifers will come back up. Whether that takes 20 years or 50 years is something I haven’t seen calculated.”

Other research suggests that the climate-related impact on agriculture across Mexico will be so devastating that it will inspire a massive wave of migration into the U.S., further straining resources. So that recharge will mostly likely be very slow to come, if at all. •