After a white police officer shot an unarmed black man in a small St. Louis suburb, a national conversation about race rocketed into a national zeitgeist.

Police clad in body armor and wielding long guns greeted protestors who descended on Ferguson, Missouri, with tear gas, batons and many arrests.

And then another conversation started: Was that too much force and how’d police get all that riot gear and all those military-style guns? Enter the Department of Defense’s 1033 Program, which provides police with surplus military equipment at no cost. Following the events in Ferguson, it has come under harsh scrutiny in the national press.

With that in mind, the Current submitted open records requests to the San Antonio Police and the Bexar County Sheriff’s departments seeking inventories of all equipment obtained through the 1033 program. We also asked for applications filed this year, along with applications to the Homeland Security Grant and Urban Area Security Initiative programs, which dole out funds to agencies for the purpose of preparing for a terrorist attack, major disaster and other emergencies.

In a September 2 letter to Attorney General Greg Abbott, the City of San Antonio asked whether it could withhold the information (with the exception of its 2014 request to participate in the program). But on September 15, the City partially reversed course after it learned the AG denied a similar request, and it released the 1033 program inventory. The request to withhold information about the Homeland Security Grant Program and the Urban Area Security Initiative applications is pending.

The City argued releasing the information, including the 1033 inventory, “would interfere with the detection, investigation, or prosecution of a crime.” Because of San Antonio’s proximity to the border and the Eagle Ford Shale, the City suggested, cartels or terrorists could use the information to thwart the response of South Texas law enforcement.

“Violence along the U.S./Mexico border has continued to thrive, and this vulnerability leaves residents susceptible to the dangers of human smuggling, drug trafficking and the threat of terrorist groups entering our country. By revealing the details that the entity is required to submit to justify receiving grant money, specific regional response capabilities for San Antonio and the San Antonio Urban Area (SAUA) would be revealed,” the September 2 letter states.

As for the Eagle Ford Shale: “the massive quantity of chemicals that are being transported both on the road and the rail [sic] the threat of a chemical release is greater than ever,” the letter suggests. “The chemical trucks and rail cars have very little security around them which make them very accessible to an active terrorist.”

Man, at this point, we feel like maybe we’re being un-American by filing an open records request. No one wants to compromise national security.

“In summary,” the letter concludes, “release of the items … would undermine the efforts of the San Antonio Police Department and other law enforcement agencies to combat terrorism and other criminal activity.”

That’s heavy stuff.

So it was surprising that much of the inventory on the 1033 list the City agreed to release consists of gym equipment, cold-weather gear and gloves.

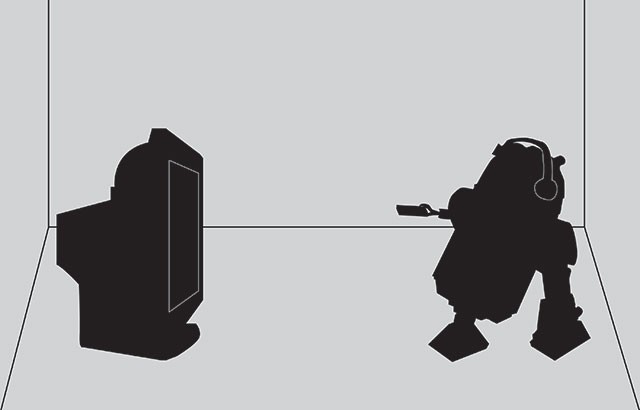

The document reveals that SAPD has participated in the program since 1997, but only filed two applications between then and 2011, for canopy parachute netting (1) and camouflage screening (3). Between 2012 and 2013, the SAPD acquired 586 items, which are used by the SWAT team. Three hundred and fifty-three of those items are cold-weather gear, like parkas. The department also received 44 pieces of gym equipment; 15 assault backpacks; 31 gloves; seven magazine holders; 13 load-bearing vests; five knives and an assortment of other items, including a step stool, storage boxes, medical supplies, a bomb-defusing robot and two LG flat-screen TVs—not exactly the kind of stuff that would jeopardize a criminal investigation or expose a vulnerability to terrorists.

As for the sheriff’s office, Bexar County Public Information Officer Laura Jesse explained that the department hasn’t acquired military equipment through the 1033 program since 2006. Requests from the Department of Homeland Security Grant Program and Urban Area Security Initiative program have to be approved by Bexar County Commissioners Court—which happened last week. Those grants help fund the Bexar County Sheriff Department’s SWAT team, among other uses.

Combined, the grants bring $652,600 into the sheriff’s budget. Of that amount, $141,000 goes toward sustaining the SWAT team and the rest is spent on various preparedness projects, maintenance, audio and visual upgrades to emergency response vehicles, and to sustaining the regional hazmat response team.

While it’s true the SAPD and Bexar County sheriff maintain arsenals and use high-tech gadgets to combat crime, protect property and conduct investigations, the weapons they use aren’t coming from the 1033 military surplus program.

Perhaps the SAPD gets that equipment from the other two programs, though public records show those grants for the sheriff’s department weren’t used to obtain weapons, though they can be used to purchase “equipment” that can be used for Homeland Security purposes. We look forward to hearing from the attorney general.