Four people are kidnapped and beaten, possibly tortured. They are bound, gagged and taken out to a remote rural area where they are executed with a bullet to the head. Then they're left to rot in the elements.

No one would fault you for thinking this is likely a scene right out of the war-torn Middle East, where the fundamentalist terrorist group Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, or ISIS, has run roughshod over the land. As it takes over huge swaths of territory, the well-funded organization commits barbaric atrocities on a daily basis, even beheading American journalists.

But we're not talking Syria or Iraq—actually, much closer to home. Mostly gone from the headlines though just as brutal and even deadlier in nature, the bloody drug war in Mexico just a few hours' drive from San Antonio drags on, producing a staggering estimated death toll of 70,000 over the last decade.

Many critics accuse the United States of turning a blind eye to its neighbor's suffering, despite direct U.S. involvement since the high demand for drugs north of the border has not abated.

Just south of the Texas-Mexico border, ruthless drug cartels like Los Zetas and Cartel del Golfo operate with impunity, often in close collaboration with corrupt government officials. These transnational criminal organizations have unleashed deadly violence on innocent people, including decapitation, mass murder, kidnappings, torture and other horrible crimes against humanity.

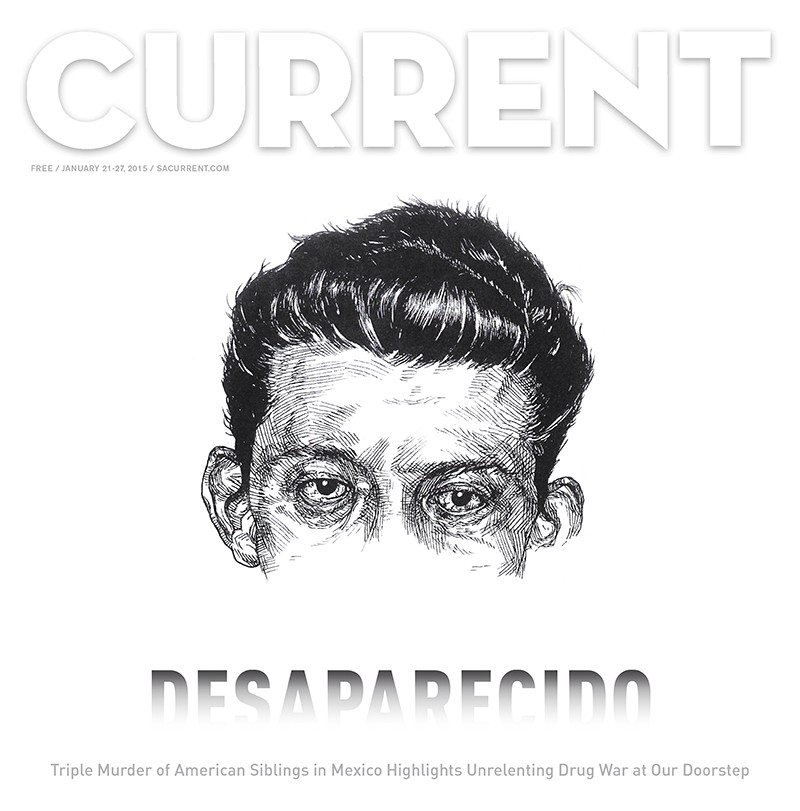

One case that briefly captured the attention of American media outlets was that of three siblings from Progreso, a small U.S. border town nestled between Harlingen and McAllen in the Rio Grande Valley, the southernmost tip of Texas.

The siblings were reportedly kidnapped by a government official's military-style bodyguard unit. The victims—U.S. citizens Erica Alvarado, 26, and her brothers, Alex, 22, and José Ángel, 21, as well as her boyfriend, Mexican citizen José Guadalupe Castañeda Benítez, 32—were later found bound, gagged and badly decomposed. They were all shot in the head. Sadly, their story is not uncommon in the volatile Texas-Mexico border region.

"This is not an isolated event. This has been repeated," notes Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera, a professor at University of Texas at Brownsville and a border violence expert.

Neighborly Neglect

Mexico is our neighbor and one of our top trade partners, and its culture plays an integral part of the American melting pot, but an honest national conversation about crimes against humanity garners little attention—even though cartels are responsible for a higher count of American casualties compared to atrocities committed by ISIS.

Drive 281 brush-laden miles south of San Antonio, through the subtropical Rio Grande Valley, and, across the border from Brownsville, you'll end up in Matamoros, the second-most populous city in the state of Tamaulipas, which many observers consider ground zero for the country's drug war.

The Valley and Tamaulipas have an intimate connection. Many Mexican-American families have relatives in Tamaulipas, and there is a thriving border culture that reflects the language and traditions of both countries. However, for years now, the U.S. State Department has included Tamaulipas in its Mexico Travel Warning, advising Americans to steer clear of the state. The most recent warning, issued on Christmas Eve, noted that there are safe resort areas which thousands of citizens safely visit each year.

But there's also a dark side to this typically hospitable land.

"Crime and violence are serious problems and can occur anywhere. U.S. citizens have fallen victim to criminal activity, including homicide, gun battles, kidnapping, carjacking, and highway robbery," the warning states.

Correa-Cabrera said she's heard various versions surrounding the murder of the Progreso siblings—they may have been involved in organized crime, particularly with the illegal sale of gasoline and drug trafficking. But no one knows for sure, and there's no official account of the investigation.

"Everything is unofficial," she says. "I think that the U.S. Consulate in Matamoros should have a little bit more knowledge of what is happening. We are talking about U.S. citizens being abducted and kidnapped."

The victims represent a fraction of Americans who were killed in Mexico in recent years. According to the State Department, 81 Americans were murdered in Mexico in 2013, jumping to 85 last year.

Many Americans killed south of the border were originally kidnapped by cartels and other criminal organizations—more than 130 last year. The count is likely much higher, since only a fraction of the cases are reported to police.

In Tamaulipas, thousands of people go back and forth into Texas to eat, shop, visit family and friends, and for work. But as the hustle and bustle of daily life goes on, the danger stemming from the drug war lurks night and day.

"We are talking about neighbors, commerce and economic links," Correa-Cabrera said. "The United States should be worried about the people who have been kidnapped and murdered."

While mainstream U.S. media outlets have largely ignored atrocities committed in Mexico, the U.S. government, through programs like the $2.4 billion Merida Initiative, fund federal Mexican military operations against cartels. And U.S. law enforcement agencies have played a key role on the ground, from the FBI to Homeland Security and the Drug Enforcement Agency.