In 1969, on the phone for a routine promo interview, Tejano singer Little Joe sparked the coincidence that would align him with the Chicano cultural movement.

Chatting about an upcoming concert on a San Jose radio station, the DJ asked Joe about his thoughts on the work of César Chávez and the United Farm Workers. "They asked if I agreed with some people who thought he was communist," says Joe, speaking with the Current. "It pissed me off. I remember telling him that people talk because they have mouths and they like to shoot them off. Then I said I was a supporter of César Chávez."

Joe hung up briskly, returning to his sound check for the impending gig. But an incoming call intruded again. "I thought it was the DJ from the radio station," says Joe, "so I went back to the phone and answered, 'yeah, what now?'"

But it wasn't the DJ. Not even close.

"It was César Chávez," Joe recalls. "He said he was listening to the interview and wanted to call and say thanks for the kind words."

The opportune call marked the first step in a lifelong friendship between Little Joe and the civil rights icon, a bond that would color Joe's career with a proud Chicano hue. In a career spanning a staggering six decades, the native of Temple, Texas, astutely embraced Mexican and American styles, earning him the coronation as the "King of the Brown Sound."

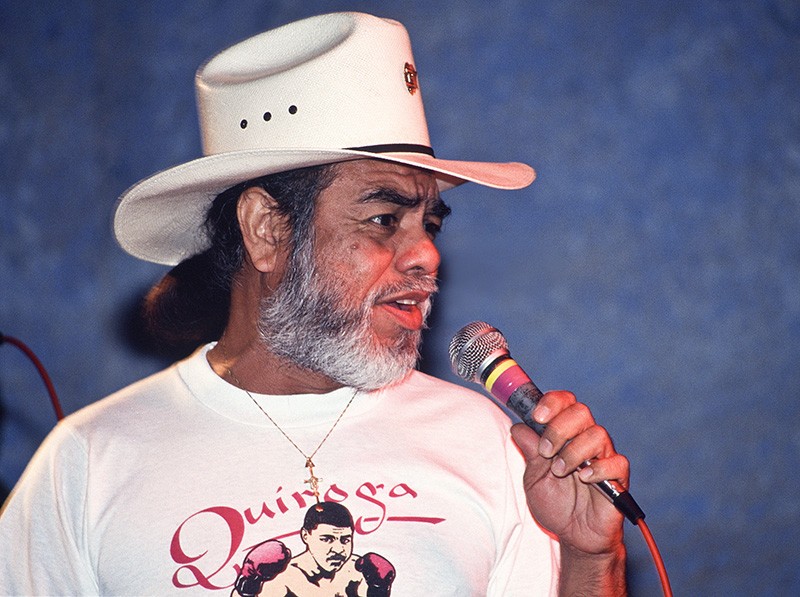

Little Joe has never been too fond of the title — in conversation last month at the Buckhorn Saloon in downtown San Antonio, he shrugs off the Tex-Mex crown, a label tacked on by a promoter with an ear for lasting nicknames. If the 74-year-old singer has a downside, it's his zealous humility.

Offstage, Little Joe downplays his stellar résumé, as if he didn't pave the way for Tejano or share '70s marquees with stars like Santana and Frank Zappa.

For years, Little Joe dodged numerous requests to collaborate on a film about his life and career. But, with the upcoming Recuerdos: The Life and Music of Little Joe, he seems to have changed his tune and now feels ready for his story to be told.

"I hope there's a lot of learning to be had from this documentary," says Joe. "It's not just for Chicanos or Latinos, it's especially for those who don't know who we are. Or know who we are, but know very little about the culture, music and contributions."

Speaking with Little Joe — loose-tied, silver-haired and sharp-tongued — he seems excited about the documentary on his life's work. Directed by Austin filmmaker Gary Wilson, Recuerdos will be the first full-length treatment of his social and musical impact, slated for release in Spring of 2016.

"Music is so vital to political struggle," Wilson tells the Current. "That's why Joe is important."

To make sense of Joe's long career, Wilson is in the process of interviewing musicians and politicians who helped shape the story. Artists including Billy Gibbons, Ray Benson ("We didn't call it Tejano music until much later. It was just Little Joe"), Cheech Marin and Paul Rodriguez make appearances, verifying the wide reach and credibility of his music.

The proceeds from his Sunday night gig at the Guadalupe will help boost the budget of Recuerdos, a film that Joe hopes will rouse a new generation of musicians. As with the serendipitous radio interview, he says: "You never know who's listening."

Born in 1940, José María De León Hernández was the seventh of 13 children. Jim Crow carved his hometown of Temple into segregated neighborhoods, with whites isolated from black and Latinos.

The racial and ethnic divisions had a deep impact on his life and career.

With white musicians dominating the radio dial, Little Joe took in the twangy country blues of Hank Williams and the Western swing of Bob Wills. But in his neighborhood, Joe learned the energy and fiery singing of African-American music. "I lived on the black side of town," he recalls. "So when I was at friends' houses, I'd hear black music, blues and R&B."

At home, Joe dove into the culture and tunes of his parents, who had emigrated from Mexico. With the booming arrangements of orquesta, the waltzing rhythms of norteño and a few swing records thrown in for good measure, Joe's family schooled him in Tex-Mex music. It was these unofficial lessons that informed the young singer, who dropped out in seventh grade to pick cotton.

In the fields, black workers sang the blues and Mexican immigrants visited the corridos of their hometowns in Coahuila and Chihuahua. Hearing the disparate styles connect with a shared purpose — passing time during hard work — Joe began to see the roots of these genres, their common ground and how to weave this music into something new.

With the growing influence of mixed sounds all around him, it was only a matter of time before Little Joe began to make some of his own. He made his musical debut at 13, when his cousin David Coronado asked him to pick up his guitar and a stage name, choosing "Little Joe" because of his short stature.

He became the newest member of The Latinaires, a little R&B outfit with two horns and a drummer. They took most of the '50s to gain momentum, working in cotton fields and Texas factories, before making their debut in '58 with "Safari One and Two" on Corpus Christi's Terro Records.