The topic of conversation over their meal: immigration reform. Impressed with the rangy, white-haired Texan’s easy charm and apparent willingness to reach across the aisle, Sharry left thinking he could work with the freshman senator to pave an easier path to citizenship for hardworking immigrants.

“He seemed very sincere,” Sharry said of the meeting. “He uses dulcet tones and a silver tongue, and he can appear very convincing.”

But instead of serving as an ally, Cornyn repeatedly balked at Senate reform packages. In 2006, he even inserted a “poison pill” amendment into a bipartisan bill that would have become the most significant immigration overhaul in 20 years.

Sharry dubbed the senator’s strategy — publicly staking out a middle-of-the-road position then pivoting hard to the right — the “Cornyn Con.”

“You make it look like you’re trying to get to ‘yes,’ then you try to pull the rug out from underneath anyone who actually does want to get to ‘yes,’” he explained.

With Cornyn now up for reelection for a fourth term and facing what’s likely to be the toughest fight of his Senate career, the 68-year-old lawmaker is on something of a charm offensive.

A barrage of slickly produced TV spots present Cornyn as a champion of women, a fighter of sex trafficking and the guy who helped eliminate a backlog in rape kits. Another ad running on Spanish-language media casts him as a champion of the DREAM Act, the proposal that would extend legal status to undocumented immigrants who came to the U.S. as children.

The reality, critics say, is the ads are just the latest in a series of reinventions for Cornyn, who’s adept at changing his public persona with the political wind. He first came to Washington as a Chamber of Commerce Republican, then morphed into a Tea Partier once he feared a primary challenge from the right. More recently, he’s been all in for Team Trump.

But what’s been constant throughout Cornyn’s career, however, is a strategy of giving lip service to legislative ideas that enjoy the support of regular Texans while using his real political clout to carry water for the business donors that have pumped millions into his campaigns.

Cornyn’s office turned down several requests for an interview for this story. However, the senator’s allies say he understands the challenge of his current race — namely that he can’t take the support of Hispanic and female voters for granted.

“It feels like a cliché to say it, but it’s there in the data,” said Brendan Steinhauser, the veteran conservative political operative who ran Cornyn’s 2014 senate campaign. “Those are the groups that are going to swing this election.”

Cornyn opponent MJ Hegar, a decorated Air Force helicopter pilot who ran a close 2018 House race in a suburban Austin, has so far spent most of her campaign energy introducing herself to voters. However, she’s now focused on exposing the rift between her rival’s public persona and his record on the Senate floor.

“The way he campaigns is actually to say, ‘This is what I’d like to do if I wasn’t hamstrung by my corporate donors,’” said Hegar.

Hegar is scheduled to meet Cornyn in a televised debate on Friday, October 9, just four days before early voting begins.

Courtesy of Sen. John Cornyn

Cornyn meets with U.S. Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett. He said the Senate should confirm her before the year is over.

Indeed, Hegar said her first decision to run for office was prompted in part by a pay-to-play attitude she saw from Cornyn’s office when she was fighting to get women the ability to serve in combat roles in the military. When she called on his office, she could never get a meeting.

“I was partnered with the ACLU,” she said. “It wasn’t like I didn’t know what I was doing.”

Last December, after a Houston Chronicle story revealed that 80,000 U.S. citizenship applications in Texas were mired in backlog, Progress Texas and eight other groups sent a letter asking Cornyn to investigate. They got no response.

“He’s a wolf in moderate’s clothing,” said Ed Espinoza, Progress Texas’ executive director. “He may not be as bombastic as Ted Cruz, but his voting record is just as bad.”

Indeed, Cornyn voted with Cruz 95% of the time in 2017 and 2018, according a ProPublica analysis of their records.

Observers say Cornyn has escaped the revulsion many Texas voters have for Cruz because he eschews bombast. Rather than pick fights with celebrities on Twitter or deliver acid-tongued soundbites, Cornyn operates as a legislative insider who speaks in moderate tones softened by a Texas drawl.

Cornyn possesses the “uncanny ability to project visually and substantively as a personification of the status quo,” as Jim Henson and Joshua Blank of the University of Texas’ Texas Politics Project wrote in a recent analysis of the senator’s current race.

But critics take it a step further, saying the senator has used his geniality to paper over his repeated attempts to dismantle the Affordable Care Act, a move that would strip healthcare from 1.7 million Texans and remove protections for those with pre-existing conditions.

Cornyn voted as recently as last week in favor of the lawsuit that seeks to dismantle the ACA in the U.S. Supreme Court, tweeting the same day that “the left… overstates the problem of pre-existing conditions to justify political control of health care.”

Even the claims in his recent TV spots don’t fully stand up to scrutiny, his detractors argue. In the case of the rape kits legislation, Cornyn voted twice against reauthorizing the Violence Against Women Act, which included provisions to reduce the rape kit backlog.

“John Cornyn comes across as a nice man, but he’s a nice liar,” veteran Democratic political consultant Laura Barberena said.

San Antonio origin story

While Cornyn, the son of a U.S. Air Force colonel, now splits his time between D.C. and Austin, the origins of his political rise extend straight from San Antonio, where he got his BA at Trinity University and his law degree at St. Mary’s University.

While working as an attorney in the Alamo City, Cornyn fell into the orbit of up-and-coming conservative political strategist Karl Rove, who shared his interest in reining in trial lawyers who’d made a mint suing big corporations, insurance companies and doctors.

Conservative court reformers recruited Cornyn to run for district judge — although in his early 30s at the time, his prematurely gray hair made him look the part. He won the race and built a record as a competent member of the bench with a pro-business record.

As Rove’s political star rose, he focused on flipping the Democrat-dominated Texas Supreme court, which he and other conservatives considered a virtual ATM machine for trial lawyers.

After Rove had already flipped several of those seats, Cornyn made a 1990 run for the court that ended up giving the GOP a business-friendly majority. A primary upset on the other side pitted Cornyn against a relatively unknown attorney with the liability of being named Gene Kelly — like the old Hollywood actor. Cornyn waltzed past him for the victory.

“John’s always been lucky,” said longtime Austin lobbyist Bill Miller, who ran that campaign for Cornyn. “He’s always had good fortune.”

The Texas Supreme Court gained the decidedly pro-business tilt Rove was after. Meanwhile, the conservative consultant’s war chest and clout continued to grow.

In 1997, Rove again struck an alliance Cornyn, convincing him to run for Texas Attorney General against Dan Morales, one of the few remaining Democrats in statewide office, according to a lengthy Texas Observer investigation of Cornyn’s career of pro-business maneuvering. At the time, Morales was riding the high of the state’s massive $15.3 billion settlement with Big Tobacco.

Cornyn intervened into the case as a private citizen, suing to draw attention to the $2 billion payout a group of trial lawyers stood to make under the settlement. He also announced that if elected AG, he’d launch an investigation into the payout.

Morales dropped out of the race, giving Cornyn another easy break. He trounced his Democratic opponent, becoming the first Republican elected Attorney General of Texas since Reconstruction. Under his watch, the office underwent the same pro-business makeover experienced by the Texas Supreme Court, critics argue.

During that time, Cornyn and several other right-wing state attorneys general launched the Republican Attorneys General Association to push state AG’s offices in a more pro-business direction, according to the Texas Observer’s investigation. By 2002, the fund had pulled in more than $5 million in corporate donations, including $721,000 from Enron, the Houston energy company that flamed out one of the biggest stock scandals of all time, according to an analysis by watchdog group Texans for Public Justice.

“It was a slush fund. A shakedown. It was a corporate protection racket,” Texans for Public Justice Director Craig McDonald told the Observer. “You could see that as soon as the thing had come into existence.”

Quiet conservative

Cornyn’s next political stairstep came with the retirement of Republican U.S. Sen. Phil Gramm. He defeated Dallas Mayor Ron Kirk for the spot and became a key ally of fellow Texan George Bush, who then sat in the White House.

While Cornyn avoided fiery rhetoric, his record was deeply conservative. He served as a principal cheerleader for Bush’s invasion of Iraq, granted green lights to the president’s conservative judicial picks and advocated for a constitutional amendment that would have banned gay marriage.

By the end of 2012, Cornyn had also climbed to the position of minority whip, becoming a key ally of Kentucky Sen. Mitch McConnell, who would two years later become majority leader.

“The way you advance in the Senate is to develop a reputation as someone who you can trust and who will be a straight shooter,” Cornyn told the Texas Tribune last fall. “And I’ve tried to do that.”

Cornyn’s ability to deliver for big donors, cozy up to powerful allies and deliver a conservative agenda without rocking the boat helped ensure his staying power, observers say. His supporters praise his ability to work play well with others while ensuring that he can continue to build his own career.

“He’s a very social animal,” lobbyist Miller said. “At the same time, he’s an ambitious guy.”

Steinhauser said he remembered feeling nervous about meeting Cornyn in a room at San Antonio’s Hotel Valencia to discuss coming on board to run the senator’s 2014 campaign. He expected a cross examination, but instead got an engaging, two-way conversation that illustrated Cornyn’s skill at building alliances.

“I thought, ‘This guy is humble, he’s smart and he asks good questions,’” Steinhauser said. “He wanted to get to know me and understand what I could bring to the team.”

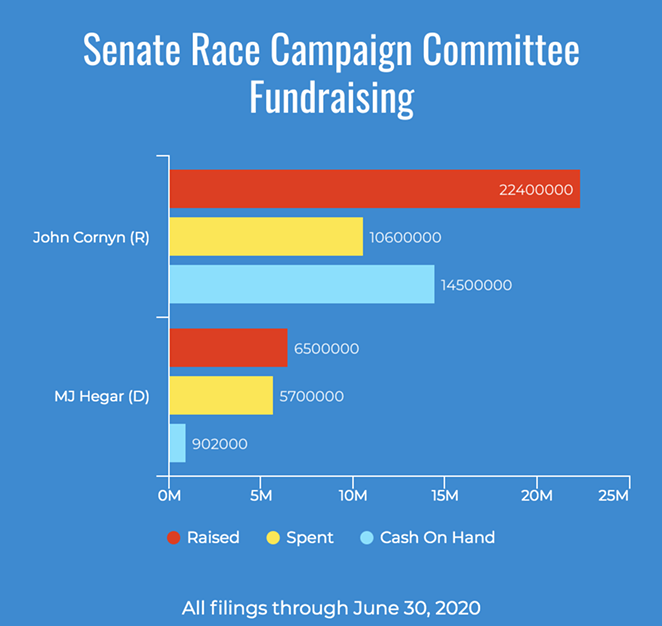

In the end, Cornyn thought it was a good match. Working with Steinhauser, the senator “never broke a sweat” during the 2014 campaign, the Dallas Morning News wrote. After swatting away a primary challenge, he went on to raise $14 million, vastly outspend Democratic candidate David Alameel and end up with 62% of the vote.

Loyalty test

It’s unlikely things will go so smoothly this time around.

Texas’ demographics are shifting, and Cornyn is likely to face blowback from voters disgusted by President Donald Trump’s perceived mishandling of the coronavirus pandemic, coarsening of political discourse and apparent unwillingness to guarantee a peaceful transfer of power.

To be sure, Cornyn was among the first high-profile GOP leaders to warn that Texas was no longer in the bag for Republicans, warning shortly after the 2018 election that the state was no longer “reliably red.”

While being a Republican under Trump is hard enough, critics charge that Cornyn’s tendency to go along with the crowd has created the perception he’s among the president’s biggest enablers.

Time and time again, Cornyn has backed away from criticizing Trump’s most outrageous pronouncements as commander-in-chief, sometimes dismissing them completely then adjusting his message after it becomes clear he’ll face blowback if he doesn’t offer a harsher critique.

Last month, after Bob Woodward revealed that Trump admitted to deliberately downplaying the danger of the coronavirus, Cornyn’s first response to reporters was that he didn’t trust the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist as a source.

Later that same day, as the story grew in prominence, Cornyn offered a revised take.

“Well I understand the intention, that he didn’t want to panic the American people, that’s not what leaders do,” Cornyn said. “But I think, in retrospect, I think he might have been able to handle that, in a way that both didn’t panic the American people but also gave them accurate information.”

Cornyn faced heat for his reticence to call out Trump during a recent Austin-American Statesman editorial board meeting at which staffers peppered him with questions about his record of lukewarm responses to the president.

“[I] try to manage that relationship in a way that helps me be productive and helps me deliver benefits to Texas,” Cornyn said.

He added: “If you engage in a public brawl with the President of the United States, that’s just not going to happen.”

Elections and consequences

While Cornyn’s avoidance of controversy and his series of public reinventions have paid off politically, critics say time finally may be catching up.

“He’s drawn significant support from business leaders and from Latinos who believe he’s a sincere man,” said U.S. Rep. Joaquin Castro, D-San Antonio. “In reality, he’s an insincere man who’s trying to get reelected. He’s overdue for this kind of blowback. The people who think he’s sincere need to know he’s not and take that to the ballot box.”

Observers say Cornyn is especially vulnerable if Texas goes blue at the top of the ticket. However, Hegar faces the challenge of building her brand after getting a late start in the campaign due to her runoff against State Sen. Royce West. She’s also hamstrung by the pandemic putting the brakes on in-person campaigning.

RealClearPolitics shows Cornyn ahead of her by an average of eight points in the polls.

However, Hegar pulled in $13.5 million in campaign donations for the third quarter, nearly four times her second-quarter haul. At press time, Cornyn hadn’t yet released third-quarter numbers.

For Hegar, the challenge so far has been running an accelerated campaign to make sure voters know her story. Now, she said, she’s ready to make sure Texans fully understand Cornyn’s record.

“I think he has really underestimated Texans’ capacity for detecting bullshit,” she said.

Even so, observers point out, Cornyn has never lost a race, and he’s once again drawing from a playbook that’s served him well over a 36-year political career.

Stay on top of San Antonio news and views. Sign up for our Weekly Headlines Newsletter.