With the probable exception of toilet paper, Texans will pay a premium for anything branded by the Lone Star State. Be it pocket knives, baby onesies or pickup trucks of unusual size, we're a people who drop serious cash for the sake of regional pride — and it's doubly true when it comes to our beer. Yeah, the macros have moved a lot of units by plastering their cans of fizzy yellow swill with that beautiful flag, but in these (hop) heady times, real Texans are keeping their cold ones in-state.

But one nagging question persists for the locavore/state supremacist in me: are these brewskis 100 percent TX? They're hecho en Tejas, clearly. Many sport the "Go Texan" logo somewhere on their label. When I check out the grain bills and the hop lists, however, the malt comes from Germany and the hops hail from New Zealand. It made me wonder if it's possible to brew without ever leaving the Republic.

Water, I learned, is the easiest ingredient to source, recent drought notwithstanding; moreover, the moderate hardness of our aquifers contributes to our flavor profiles. Employing native yeast requires a degree of surrender to the whims of nature, but it can be done. Jester King seems to have had pretty good luck with it.

It's the other two basic beer ingredients that complicate matters. Malt comes from grain, primarily barley, which was only grown for cattle feed here until a few years ago. Today, Blacklands Malt have homesteaded a native malt provider up in Leander, where proprietor Brandon Abe oversees the overturning of small mountains of moist, germinating grain. It's a very promising venture, but it will take many Blacklands to meet Texas' demand.

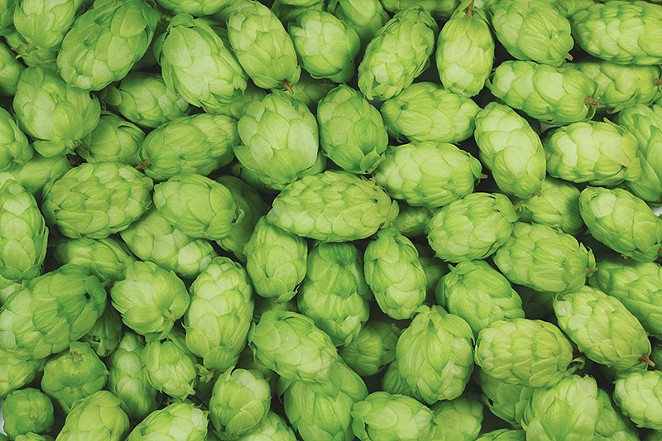

Hop prospects are even worse. As Vera Deckard, brewmistress of The OK Brewery And Eishaus, told me, "there is no such thing as Texas hops. Hops don't grow here, unless they are babied, and then the yield is small." There are several reasons for the lack, but the chief culprit is that inescapable heat — hops thrive in cool, wet regions, and that just ain't gonna happen here.

The German freethinkers who settled Central Texas also didn't have hops, but they found a decent alternative in the fruit of the wafer ash, aka the hop tree. It still grows here. Perhaps some enterprising young brewery will try it out, pitching the native shrub with some hydroponic Centennial cones (are you reading this, Planet K?) and some pure prairie two-row malt from Alpine or Fredericksburg. Sure, nobody's used the hop tree in a commercial beer before, but Texans are nothing if not enterprising. If you have the chance to brew a beer that's nose-to-tail native, I say come and take it.