It ended 90 minutes later at the Steel House Lofts, five blocks down South Flores, where SAHA CEO and President David Nisivoccia lives. The group that included Alazán Courts residents turned right on West Peden Alley, as a small caravan occupied a lane on Flores and honked their horns. In the alleyway, they chanted, “Shame on SAHA, shame on David!” and “Mi barrio no se vende!” (My neighborhood is not for sale) as they looked up at the four-story condominiums.

Nisivoccia, who has ramped up SAHA’s production of mixed-income apartments since he became CEO in 2016, is leaving in January to become executive director of the Denver Housing Authority.

SAHA spokesman Michael Reyes said Nisivoccia was not available for an interview on Saturday, but instead issued a statement.

“Today’s protest at the home of a SAHA staff member is another demonstration of the Esperanza Center choosing intimation and scare tactics over truth or productive dialogue,” Reyes wrote.

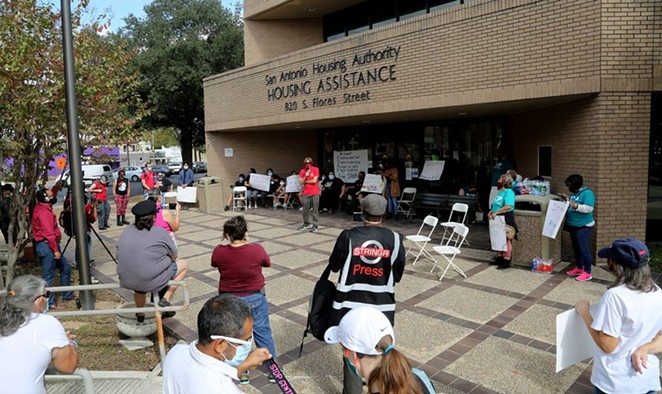

To be clear, Saturday’s protest was by a group composed of the Coalition For Tenant Justice, the Historic Westside Residents Association, Texas Organizing Project, the San Antonio Tenants Union, along with the Esperanza Peace and Justice Center and other housing advocates.

Reyes’ statement went on to describe the protest at the Steel House Lofts as “uncivil” and that SAHA does not condone protests that “jeopardize the safety of our leadership and staff members.”

At no time did the protest get out of hand or become violent. If it was anything, it was loud, as the group shouted, “What do we want? Housing! When do we want it? Now! If we don’t get it? Shut it down!” When cars or delivery trucks entered the alley, the group moved out of the way to let them pass. Some of the Steel House Lofts residents observed the protestors from their balconies.

“We have invited them to the policy discussion and have attempted to explain the affordable housing crisis, yet they refuse to understand it because it doesn’t align with their political agenda and fundraising efforts,” Reyes said of the Esperanza in a lengthy statement.

The event’s organizer, Kayla Miranda, who’s also a member of the Historic Westside Residents Association, and a SAHA resident, said in response, “We have every right to go to David’s home. He filled out the paperwork with the city same as other officials and commissioners. … And he’s coming after our homes. Why shouldn’t we confront him in his?”

In a lengthy response of her own, Graciela Sanchez, director of the Esperanza, said, “I have no idea of what policy discussions he speaks of. All we have been able to do is attend the monthly SAHA meetings and speak for 3 minutes, unless of course, we’re limited to 1.5 minutes because too many folks wanted to speak against demolition of the Alazán Courts.”

Sanchez was referring to the SAHA board limiting time for citizens to be heard at the meeting in early November because of the sheer volume of people who signed up to speak, more than 60, on Alazán Courts.

The fierce debate over SAHA’s development strategy, which calls for eliminating San Antonio’s remaining public housing communities, while partnering with for-profit developers to build mixed-income apartment complexes, has only escalated between the authority and its supporters versus a growing number of housing activists with each step the authority takes.

On November 5, the SAHA board of commissioners voted 5-2 to seek permission from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to demolish Alazán’s 501 units on the near West Side, and replace them with a mixed-income community to be built by Cleveland-based developer NRP Group in the coming years.

Mayor Ron Nirenberg, in a letter of support dated November 3, has backed the plan and wrote, “It will provide modern quality apartment homes for families at a variety of income levels.”

Activists and preservation groups have called for rehabbing the 80-year-old courts—a collection of decaying, barracks-style public housing units spread across 26 acres along Alazán Creek. Roughly 1,200 people, whose average yearly income is $8,700, currently live there.

The activists describe the redevelopment as a massive displacement, one in which 1,200 people would be scattered throughout the city. They point to the former Wheatley Courts on the East Side, where, in 2014, roughly 200 families were forced to leave the area to clear the way for SAHA’s 414-unit East Meadows mixed-income community. Also, see the Victoria Commons as another large-scale example. SAHA has admitted it made a mistake by demolishing the Wheatley Courts all at once, and therefore plans to raze and rebuild at the Alazán site in at least two phases.

SAHA says annual funding from HUD has dwindled, and doesn’t have the means to build large amounts of new affordable housing on its own. It also doesn’t have the funding to maintain and repair its aging public housing stock, the agency says. The mixed-income projects, in which SAHA provides a toolkit of subsidies to private developers, will provide much needed revenue that will bolster its reserves, which can then be used to subsidize more below market-rate housing down the line.

In a recent SAHA board meeting, Nisivoccia said he estimates the agency has roughly $7-8 million annually to spend on the remaining 6,000 public housing units.

“If you take the average cost of wanting to renovate or fix up versus redevelop, about $100,000 per unit, at 500 units: that’s $50 million,” he said at the October meeting. “That would be about 10 full years of our capital fund program and ignoring the rest of our portfolio. I want all the residents to know and understand: We’re not ignoring Alazan. It’s just a financial challenge. … The deterioration of Alazan has been happening over 20-30 years.”

But housing activists don’t buy it. They question the math behind the systemic elimination of public housing units in San Antonio at a time when SAHA’s wait list for affordable housing has grown to more than 45,000 families compared to 15,000 in 2000, according to San Antonio Express-News archives.

“We are insulted that he thinks that they need to explain to us about the affordable housing crisis,” Sanchez said. “What was the demonstration about except to say that affordable housing isn’t even affordable to public housing tenants, and their current housing policy is mixed income housing.”

During the rally, Alazán Courts resident Jacquline Caldwell described SAHA’s new business model as a public housing holocaust. SAHA has said it plans to demolish the remaining public housing stock: The nearby Apache, Cassiano and Lincoln courts, and replace them with mixed-income communities.

“Stop this holocaust,” said Caldwell, a mother of two. “Stop killing our homes. Stop killing our communities. Stop mass murdering all of our dreams and expectations and aspirations so that you all can profit.”

Big picture, SAHA says it’s actually creating more affordable housing by partnering with for-profit developers. Currently, SAHA has more than 8,800 mixed-income apartments it is either constructing or planning with another developer. Alone, the agency says, it would build a fraction of that amount if it were just building subsidized apartments.

From 2008 to 2018, the agency produced 3,500 units.

At Alazán, the new apartments are projected to have some public housing units, but also market-rate units. SAHA is also building other mixed-income communities on the West Side, including the 200-unit Tampico Lofts near San Fernando Cemetery No. 1. But West Side activists criticize the development, which is a SAHA partnership with developer Mission DG, for only having nine units priced for people making up to 30% of the area median income, or, the most needy. It has a range of other affordable rents; while 64 are priced at market rate.

SAHA contends the financial cost to rehabilitate Alazán Courts is higher than the cost to demolish and rebuild. The agency says current Alazán Courts residents will have first dibs at one of the new apartments, should they choose to return to the site. They can also move into one of the newer developments SAHA is building. Or, they will be given Tenant Protection Vouchers from HUD, which they can use to find housing elsewhere in San Antonio.

Housing activists point out that landlords don’t have to accept the voucher, and that some end up losing a voucher that was never used.

Like at East Meadows, as well as Hemisview and Refugio Place just south of downtown, SAHA envisions the Alazán apartments with a range of rents, for people in public housing to people who can afford to pay market rate.

Although the East Meadows master development had the support of President Obama’s $30 million Choice Neighborhood grant, which was partly designed to mitigate the harmful effects of such a move on families with little means, many of them still suffered the move, Olga Kauffman, who sits on SAHA’s board, and who worked directly with Wheatley Courts families at the time, told the Heron recently.

SAHA has begun to put together a plan to help families with their credit scores, and other potential impediments to finding housing with a voucher in hand. For more on their plan, view SAHA’s presentation for relocating Alazán residents at its November 5 meeting.

Nirenberg agrees with the strategy.

“We recognize that displacement can destabilize and harm residents,” the mayor wrote in a statement to the Heron. “As SAHA prepares for the next steps, we look forward to reviewing the Relocation and Re-Occupancy Plan for Alazan Courts residents, which we intend to ensure centers and addresses their comprehensive needs throughout the changes ahead of us. The process must thoroughly address displacement concerns.”

Nirenberg did not return several direct interview requests for this article.

SAHA says the majority of residents it polled earlier this year prefer the voucher. The Heron obtained copies of the survey, which was stopped because of the pandemic, and which SAHA has authenticated. View the survey here, and the results here.

The San Antonio Heron is a nonprofit news organization dedicated to informing its readers about the changes to downtown and the surrounding communities.Stay on top of San Antonio news and views. Sign up for our Weekly Headlines Newsletter.