Courtesy Photo / Grand Hyatt

Roughly 70% of the Grand Hyatt’s room revenue comes from conventioneers, according to Moody’s Investors Service.

Noin, the head server at the Esquire Tavern, spent most of his adult life working in San Antonio’s hospitality sector and thought he knew what to brace for. Then, his restaurant closed the day after Mother’s Day, only reopening again for full service in November.

“I started buckling down and saving money once I recognized what was happening,” said Noin, 53. “But I never expected to be out of work for six months.”

After that experience, Noin’s read on what the COVID-19 crisis has done to San Antonio’s tourism and hospitality industry lines up with that of economists and industry observers: it will take years, not months, to rebuild.

The significance of that impact can’t be undersold. Tourism is the third-largest sector of the local economy, employing one out of every seven San Antonians. What’s more, experts warn that the industry, which local leaders spent decades and millions of dollars cultivating, will be profoundly and permanently altered once it returns.

“The leisure visitors are what will carry us until things get back to a better place,” said Dave Krupinski, interim CEO of Visit San Antonio, the city’s independent tourism marketing arm. “It will take years to get back to where we were on group travel.”

To be more precise, Krupinski predicts that leisure travel to San Antonio won’t return 2019 levels until 2023 or 2024. Group travel, such as conventions and business meetings, won’t hit pre-pandemic levels again until 2025 — possibly longer.

That latter projection is a big deal because group travel is what fills downtown hotels, and conventioneers on corporate accounts tend to spend bigger than frugal family travelers. Of the 39.2 million visitors that came to San Antonio in 2018, nearly 20% came for business, according to a study by travel research company DK Shifflet & Associates.

As of January 4, the city has lost nearly 260 conventions and in-house meetings due to cancellations, according to Visit San Antonio. That amounts to a loss of 634,251 room nights in local hotels and $431.3 million in economic impact.

There are potential wins on the horizon, such as the NCAA Women’s Basketball Tournament the city was courting at press time. And 59 meetings are still on the books for the Henry B. Gonzalez Convention Center, representing 323,205 room nights and $198.2 million in economic impact.

But economists warn that until vaccines and herd immunity put the pandemic in the rearview mirror, San Antonio’s tourism and hospitality sectors are in for lean times.

Sanford Nowlin

Oscar Noin, who’s worked most of his adult life in hospitality, said he originally underestimated the impact of the pandemic.

In what may be the most profound sign of San Antonio’s tourism woes, the city revealed in December that it’s now covering bond payments on the Grand Hyatt convention center hotel. That city-owned luxury hotel was born through a controversial $282 million bond deal in 2015.

City officials expect to make $13.4 million in payments over the next seven months to keep the struggling hotel in operation. After the pandemic dried up convention business, the 1,000-room property laid off workers and shut down for five months.

San Antonio is now using tax revenues collected from visitors to cover the payments. That, in turn, siphons off funds otherwise that would have been used for tourism marketing, the arts and historical preservation — you know, stuff that could help rejuvenate the flagging hospitality industry.

Roughly 70% of the Grand Hyatt’s room revenue comes from conventioneers, according to Moody’s Investors Service.

While observers have tallied a moderate comeback of hotel stays outside of San Antonio’s downtown center, the numbers in the center city remain dismal.

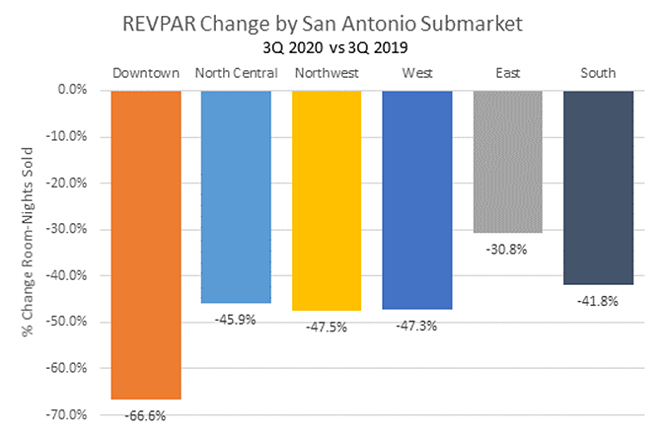

Revenue per available room, called RevPAR in the business, was down 67% from third quarter 2019 to third quarter 2020 for downtown hotels, according to San Antonio hotel consultancy Source Strategies Inc. For the quarter, hotels in the center city reported average RevPAR of $33.71, substantially below the citywide average of $38.58.

Making the best of it

The hotel numbers show that people are still traveling, just not for conventions and big-ticket vacations, Visit San Antonio’s Krupinski said. As a result, his organization is focusing its marketing efforts on attracting visitors from Texas and surrounding states. It’s also looking at ways to convince families to prolong their stays.

“As we come out of this pandemic, I think we’ll see people much more comfortable traveling closer to home,” he said.

Visit San Antonio is also launching a snappily named promotional program called “Si San Antonio” that will give travelers a special hotel rate and a card offering discounts at attractions, restaurants and museums.

First and foremost, though, Krupinski said, the city’s hospitality sector must focus on making travelers feel safe as they visit. To that end, it’s encouraging local hotels and attractions to focus on safety and has held talks with billionaire Graham Weston’s Community Labs to provide rapid, low-cost coronavirus testing for hotel staff.

Nationwide scramble

While a reshuffling of the city’s marketing efforts may help bring back some business, by Visit San Antonio’s own calculations, we’re still in for a rough ride. There’s simply no advertising budget that will cure what ails us, experts argue.

For one thing, San Antonio isn’t the only city vying to rebuild right now. The convention and visitors bureau of every U.S. city is undertaking a full-court press to attract visitors. Flip open a copy of Texas Monthly, and you’ll find Lone Star State destinations large and small taking out glossy ads to win back tourist dollars.

“If you look at the five major cities in Texas, they’re all completely hammered, especially in the downtown business district,” said Paul Vaughn, senior vice president at Source Strategies. “They’re all pushing to win back that business. It’s very competitive right now.”

Compounding the problem, San Antonio hasn’t landed any recent attractions to give it fresh sparkle for travelers, Vaughn said. While the city’s designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site may appeal to certain visitors, it’s not likely to be a big draw for families driving in from Waco or Longview for enchiladas on the River Walk.

Another problem is that businesses are rethinking how to approach conventions and other gatherings amid the pandemic. The explosion in Zoom meetings in virtually every industry demonstrates that not everyone needs to be in the same room to make decisions, get training or hobnob.

The long-term result, economists argue, is that businesses will hold fewer and smaller conventions. Those that do occur in the next few years are likely to be hybrid affairs where some folks get to rub shoulders and run up the expense account while the rest watch from video screens.

“You’re already seeing companies brag to their shareholders that they’re saving money by not traveling for meetings,” Vaughn said. “They’re saying, ‘By not spending that money we’re helping offset our losses.’”

City subsidies

While the travel downturn has been painful for every Texas metro, it’s carried a special sting for San Antonio, which spent big to leverage its history and the River Walk to establish itself as tourism and convention mecca.

The count of the city’s hotel rooms has grown from 18,600 in 1987 to roughly 52,300 this year.

Beyond issuing bonds for its convention center hotel and undertaking multiple pricy convention center expansions, San Antonio has also incentivized hotel development to boost its tourism standing. (For more on that see this issue’s CityScrapes column.)

Downtown’s Hyatt Regency opened in 1981 with some $10 million in federal aid, for example. Tax abatements also played a part in attracting the Adam’s Mark, Hixon Properties’ Westin hotel, the Hyatt Hill Country, the Westin LaCantera and the J. W. Marriott Hill Country resort, to name a few.

For critics, the hospitality industry downturn is a lesson in why public-sector efforts to bolster private-sector interests are a risky play.

“Economists in general aren’t real big on using tax revenue to attract businesses,” said David Macpherson, a Trinity University economics professor. “What you end up doing is getting in bidding wars with other communities. The real winners aren’t the taxpayers in those communities but corporate shareholders.”

Ready to Work

Other states heavily reliant on the tourism business have already been looking for other ways to diversify their economies. Calling the pandemic “excruciating” and “unprecedented,” Gov. Steve Sisolak of Nevada this month warned that his state simply can’t rely on a recovery in tourism to put people back to work.

“It’s not enough to just aim for a full reopening of our current economy,” he said in an Associated Press report. We must look forward to the kind of economy that will let our state prosper in the future,” the governor said.

While experts say it’s unclear how much leadership Texas will show in rethinking its post-pandemic economy, there’s at least one potential bright spot locally.

In November, voters approved spending $154 million on SA Ready to Work, an initiative created to provide job training and education to 40,000 San Antonians who lost work during the health crisis.]

An economic impact report on Ready to Work by local economist Steven Nivin found that every dollar spent on the program will yield $85 while costing residents an average of $8.62 per year. Nivin predicted that the program ultimately will yield $5.7 billion in increased wages plus another $7.4 billion as workers spend their boosted salaries.

While the verdict is still out on Ready to Work, observers say it represents a welcome break from San Antonio’s traditional thinking when it comes to economic development — throwing incentives at businesses and hoping we can market our way to prosperity.

“If you invest in people, they’ll have the skills that can be transferable across industries. That’s the better investment,” Trinity’s Macpherson said. “Human capital has paid off in the past for us, and it will pay off in the future.”

The Esquire’s Noin says he’d like to see San Antonio invest in its homegrown hospitality industry to save what jobs it can. But he also wants it to expand opportunities for the many workers who won’t be able to return to their hotel and restaurant shifts. A half dozen of his close friends have left the business for good, he said.

“When it happens, I think ‘Good for them,’ but I also know we’re losing good people,” Noin said. “And we’re going to lose more. This won’t be over for a very long time.”

Stay on top of San Antonio news and views. Sign up for our Weekly Headlines Newsletter.