The newlyweds descend the staircase inside an elegant, antebellum-style mansion tucked away in a private Boerne ranch, an ideal setting for a swanky wedding reception in the picturesque Texas Hill Country.

No longer in her wedding dress, the bride’s wearing a silver mini skirt, the groom still in a tux sans tie and jacket, his shirt sleeves rolled to the elbows — party attire. The groom tries to look suave, slowly unbuttoning his vest before he takes her hand and pulls her in. Then begins the choreographed strutting to the Bee Gees’ “More Than a Woman.”

Some seven months later in January 2013, when officials gathered for the 83rd Texas Legislature, Sen. Carlos Ureti’s post-matrimonial moves became the talk of the Texas Senate, with then Lieutenant Gov. David Dewhurst telling the chamber to check out the YouTube video, now viewed some 15,000 times, of the longtime San Antonio lawmaker’s wedding-reception dance routine. The event, as is common for Uresti parties, had a theme: Nside San Antonio magazine dubbed it “glamour, glitz, elegance, romance and The Godfather.”

Uresti’s reportedly got a thing for Coppola’s mafia masterpiece. He even kept a framed photo from the movie in his downtown law firm, a still from the famous restaurant scene where Michael Corleone (in the movie, a U.S. Marine like Uresti) guns down two men.

When federal agents raided that same office one morning this past February, Uresti told reporters they were simply reviewing his firm’s documents as part of a “broad investigation” into a bankrupt oilfield services company that’s been accused of defrauding investors.

The raid wasn’t exactly a surprise. Months before, in an exhaustive report, the San Antonio Express-News used federal bankruptcy court filings to detail Uresti’s questionable involvement with the company Four Winds, which tried to bank big off the South Texas oil boom by hawking sand used in the fracking process. Investors have claimed the company instead spent their money on perks like Ferraris, “wild parties” and $20,000 diamond rings. Uresti sometimes provided legal services to the company, at one point even acting as Four Winds’ outside counsel. He even helped recruit investors while maintaining a small stake in the company.

In January, a month before the feds raided Uresti’s office, one of his former clients — a Harlingen woman who won a major settlement after an exploding tire caused a car wreck that killed her two children — sued him for fraud, saying she lost almost a million dollars after Uresti “tricked” her into investing the settlement money with Four Winds. Uresti meanwhile got a $27,000 commission on the deal.

A federal grand jury last month returned two separate indictments against Uresti, one of which charges him with multiple counts of wire fraud, money laundering and securities fraud for his alleged role in the Four Winds debacle, which prosecutors have called “an investment Ponzi scheme.”

Turns out the agents who raided Uresti’s law office were looking into much more than just his involvement in the now defunct frac sand company. In the other indictment, the feds outlined a whole separate case against Uresti, one that accuses him of helping rig a private prison contract at a West Texas detention center where inmates have rioted over squalid conditions, pocketing hundreds of thousands of dollars in the process.

Prosecutors say that alleged bribery scheme goes back a decade, to when Uresti made the jump from the Texas House to the state Senate seat he now occupies. One of Uresti’s alleged co-conspirators pleaded guilty to the scheme in federal court last week and has agreed to “fully cooperate” with investigators.

While federal prosecutors have so far been tight-lipped on the many charges against Uresti (the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Western District of Texas, where the cases are filed, declined our requests for comment), in court filings they’ve alleged that the Democratic lawmaker’s “financial difficulties” drove him to commit fraud.

Last month, Uresti turned himself in to federal officials, who escorted him in handcuffs and ankle shackles to his first court appearance. After his hearing, he told reporters and TV cameras that had gathered on the federal courthouse steps, “I look forward to my day in court when all the facts come out and the truth and not just what’s been in the press.” He was flanked by wife Lleanna and a high-powered legal gun, Mikal Watts.

Watts has his own history with federal prosecutors, having been charged in 2015 with fabricating thousands of clients in lawsuits against BP following the 2010 Gulf of Mexico oil spill. A jury acquitted Watts last summer after a marathon five-week trial. Watts is now on a sort of crusade against federal prosecutors and even travels the country to deliver presentations to lawyers groups on how he beat the feds.

Watts says he sees parallels between his case and Uresti’s current legal woes. “I think federal prosecutors, some of them, are so excited about taking down a public figure that they unwittingly get blinders on and they filter out what is obvious and right in front of them and instead focus only on the things that help their objective to get a conviction,” Watts told the Current last week.

Watts insists that what has happened to Uresti (“being tried and convicted in the newspaper, the overreach from overzealous prosecutors”) is the same thing that happened to him. “It’s like déjà vu.”

If Watts is right, Uresti could again dodge a scandal that threatens to tank his political legacy – a boy from the South Side who managed to turn the family name into a local political juggernaut (brother Albert is Bexar County Tax Assessor-Collector; brother Tomas won Uresti’s old Texas House seat last year).

If he’s wrong, Uresti could face decades behind bars.

Tragedy brought Denise Cantu and Carlos Uresti together.

On August 20, 2010, the rear tire of her Ford Explorer exploded while she was driving, sending the car careening into a grassy median. The rollover killed her teenage daughter, 4-year-old son and two friends.

Uresti worked with Mikal Watts’ law firm to represent Cantu in the wrongful death lawsuit against Michelin and Walmart that scored her a substantial settlement in October 2012. In court filings, federal prosecutors say Uresti forged a personal relationship with the Harlingen woman during the case, earning her trust and confidence, “which he later exploited.”

Cantu’s lawyer has previously alleged in interviews with the Express-News that she and Uresti had an affair sometime after her legal settlement, something Uresti has vehemently denied (Cantu testified in one 2015 court hearing that she never “dated” Uresti; her Rio Grande Valley attorney Oscar Alvarez wouldn’t comment on the matter when we reached him by email last week). By 2014, prosecutors say Uresti had convinced Cantu to dump the bulk of her settlement money, some $900,000, into the frac sand company Four Winds.

Cantu would lose almost all of it by the time the company imploded in bankruptcy in 2015. While she’s not the only victim of what the feds have called Four Winds’ “Ponzi scheme” to fleece investors, prosecutors says she’s certainly the most vulnerable. As they stated in a court filing last month, “It’s hard to imagine a more mentally and emotionally vulnerable client.”

At least three former Four Winds executives have already pleaded guilty to federal fraud charges for their roles in the Four Winds scandal, including the company’s former co-owner and chief operating officer, its former e-commerce and marketing director and the company’s comptroller. Four Winds CEO Stan Bates, who was forced into personal bankruptcy soon after the company folded, was indicted alongside Uresti last month on conspiracy and numerous other fraud charges. Local consultant Gary Cain (who in 2007 was tried and acquitted of charges he swindled Rackspace out of millions in a land deal when the company moved to its Windcrest headquarters) also faces charges in the Four Winds scandal.

This month prosecutors tried to block Watts from representing Uresti in the Four Winds case because his firm helped represent Cantu, who’s now a victim expected to testify in the criminal case, in her wrongful-death lawsuit, stating in one court filing that Watts “may not represent his former co-counsel against his former client.” In a response filing, Watts says that others at the firm handled the majority of her case. In an interview with the Current last week, he called prosecutors’ efforts to toss him from Uresti’s defense “completely without merit.”

Watts also suspects the feds want him off the case because of his own victory in federal court last year (Watts, to the shock of many, represented himself at trial).

As Watts told us, “I happen to be one of the few people in America who no longer has reason to be intimidated by United States federal prosecutors.”

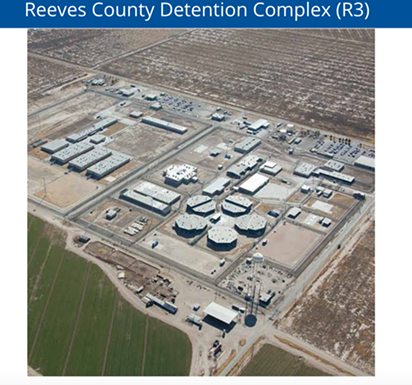

Jesus Manuel Galindo was sentenced to serve 30 months at the Reeves County Detention Center after border guards caught him swimming across the Rio Grande to visit family in New Mexico.

According to a lawsuit the ACLU of Texas later filed on behalf of his family, Galindo told private prison guards at the sprawling West Texas detention center of his history of epileptic seizures. After he complained he wasn’t getting the correct anti-seizure medication, Galindo somehow found himself in solitary confinement. He wrote his mother letters saying he’d already had seizures in isolation and was begging guards not to leave him alone in his cell.

In December 2008, Galindo suffered a grand mal seizure at night, while alone in his cell. Inmates started setting mattresses on fire when they saw guards carrying his lifeless body out of the unit. The death sparked an all-out riot, with inmates taking prison staff hostage, setting fires across the complex and causing more than $1 million in damage.

The Galindo family’s subsequent wrongful-death lawsuit listed Physicians Network Associates (PNA) as a defendant, alleging the for-profit company under contract for medical services at the detention center denied inmates like Galindo even the most basic medical care.

The second criminal case against Carlos Uresti unveiled by the feds last month alleges that two years before that prison riot, he entered into a bribery scheme to ensure PNA and its “successor companies” got and kept that contract. According to his indictment, Uresti became the vehicle for bribe money flowing from PNA president Vernon C. Farthing III to former Reeves County Judge Jimmy Galindo (no relation to the dead Reeves County inmate), who last week pleaded guilty in federal court to rigging the contract “at pricing favorable to Farthing’s Company and unfavorable to Reeves County.”

In exchange for Galindo’s help on the contract, the feds say Farthing, who also faces charges in the case, agreed to hire Uresti, then a Texas House member running for state senate, as a “consultant” and pay him about $10,000 per month. Prosecutors say Uresti would then pass roughly half that money onto Galindo.

Galindo’s plea agreement says the three men met in Fort Stockton in August 2006 to hammer out their arrangement. The next month, about a week after PNA was awarded the contract for medical services at Reeves, Farthing sent Uresti’s office a copy of their agreement for “marketing services,” including his first $10,000 payment, according to his indictment.

That’s when Farthing’s company started helping with Uresti’s run for state senate. According to filings with the Texas Ethics Commission, Uresti reported three separate in-kind contributions from PNA during the final two months of the 2006 campaign that won him the Texas Senate seat he’s held onto for a decade — free flights on the company plane worth some $5,000 in total.

By January 2007, Uresti had formed his consulting firm, Turning Point Strategies, which prosecutors claim became a funnel for bribe money flowing to Galindo. In court filings, the feds claim they’ve tracked transactions in which PNA sent Uresti a check, only to have the senator wire exactly half the amount to Galindo’s account days later with the memo “Half of PNA check.”

In an interview last week, Watts acknowledged that Galindo has in the past done work for Uresti’s consulting firm, but wouldn’t elaborate on what that work was. Uresti’s political campaign reported paying Galindo nearly $9,000 in 2010 as reimbursement for vague “event” expenditures and “contract labor.” The campaign also reported paying nearly $12,000 worth of “campaign services” and “political advertising” to a little known company called “Municipal Market Strategies,” which, as the Texas Observer first reported, shares the same address as Galindo’s longtime Pecos home.

Watts flatly denied that Uresti engaged in any illegal activity with Farthing or Galindo, calling it routine consulting work that was “completely normal, legal and appropriate.” He pointed out that Galindo has also pleaded guilty to tax evasion. “There is no conspiracy here other than by Galindo, who’s seeking to avoid a lengthy prison sentence for failing to file tax returns for well over a decade,” Watts said. (Galindo’s lawyer did not respond to our requests for comment.)

Farthing’s attorney, Cynthia Orr, denied the charges against her client in a phone interview last month and said Farthing hasn’t been an owner in the company since PNA merged with another one in 2010. She did, however, say that Farthing remains an employee of the company’s latest iteration, Correct Care Solutions, which declined comment except to say that the company has “cooperated in full with the DOJ’s investigation and has given this matter its full attention.”

Meanwhile, civil rights attorneys who closely monitor for-profit prisons say they’re deeply troubled by the alleged bribery scheme. The feds claim Uresti and Galindo received payments from PNA and its “successor companies” until late last year.

Carl Takei, a staff attorney with the ACLU’s National Prison Project, summed up his thoughts on the charges this way: “If the allegations in the indictment are correct, then people getting rich off this contract led directly to human suffering inside that prison.”

Three years after his wedding reception dance routine generated gushing headlines, another video featuring Carlos Uresti started to make the rounds in political circles.

It was undercover footage, shot by arch-conservative activists who trolled lawmakers with video cameras during the 2015 legislative session, showing Uresti cuddling at a dimly-lit bar with what appears to be a much younger woman, who at one point leans in to kiss him on the cheek. A second clip shows a woman (not Uresti’s wife) coming out of a bathroom a couple minutes before Uresti walks out the same door (to dramatic effect, all put to the Carrie Underwood song “Before He Cheats”).

It was salacious, gossipy stuff that reporters mostly ignored — that is, until Uresti’s 2016 primary challenger rolled it into a 30-second TV ad that ended with the line, “It’s time for a senator that stands up for women, instead of looking for the next good time.”

Uresti won the primary with a staggering 75 percent of the vote. To Christian Archer, Uresti’s longstanding senior campaign strategist, it was proof voters don’t believe the mud political opponents have long tried to sling at his client.

Archer also draws parallels between the criminal charges against Uresti and the case Watts defended himself against last year. Archer calls Watts his best friend, sat through every day of his five-week fraud trial in Gulfport, Mississippi last year, and is even making a documentary on the case.

“The feds have this formula for going after a big name,” he told the Current, by splashing the allegations on newspaper front pages and spinning a narrative of greed and guilt before the defendant ever gets to court. “Their press machine is built to convict you, to break you down before you ever get your first day in court.”

The general allegations against Uresti in the Four Winds case were largely known by the time voters went to the polls in November and re-elected Uresti with a healthy 15 point margin.

As Archer sees it, “He’s been vetted by voters. They clearly believe in Carlos’ record more than the narrative that’s now coming out in court.”