At about the same time as one of the most brutal dog attacks in recent San Antonio history — a South Side man had his scalp and ear ripped off by a pack of dogs in December, before a police officer arrived and shot three of the animals — the city's Animal Care Services department announced it had reached a long-elusive goal.

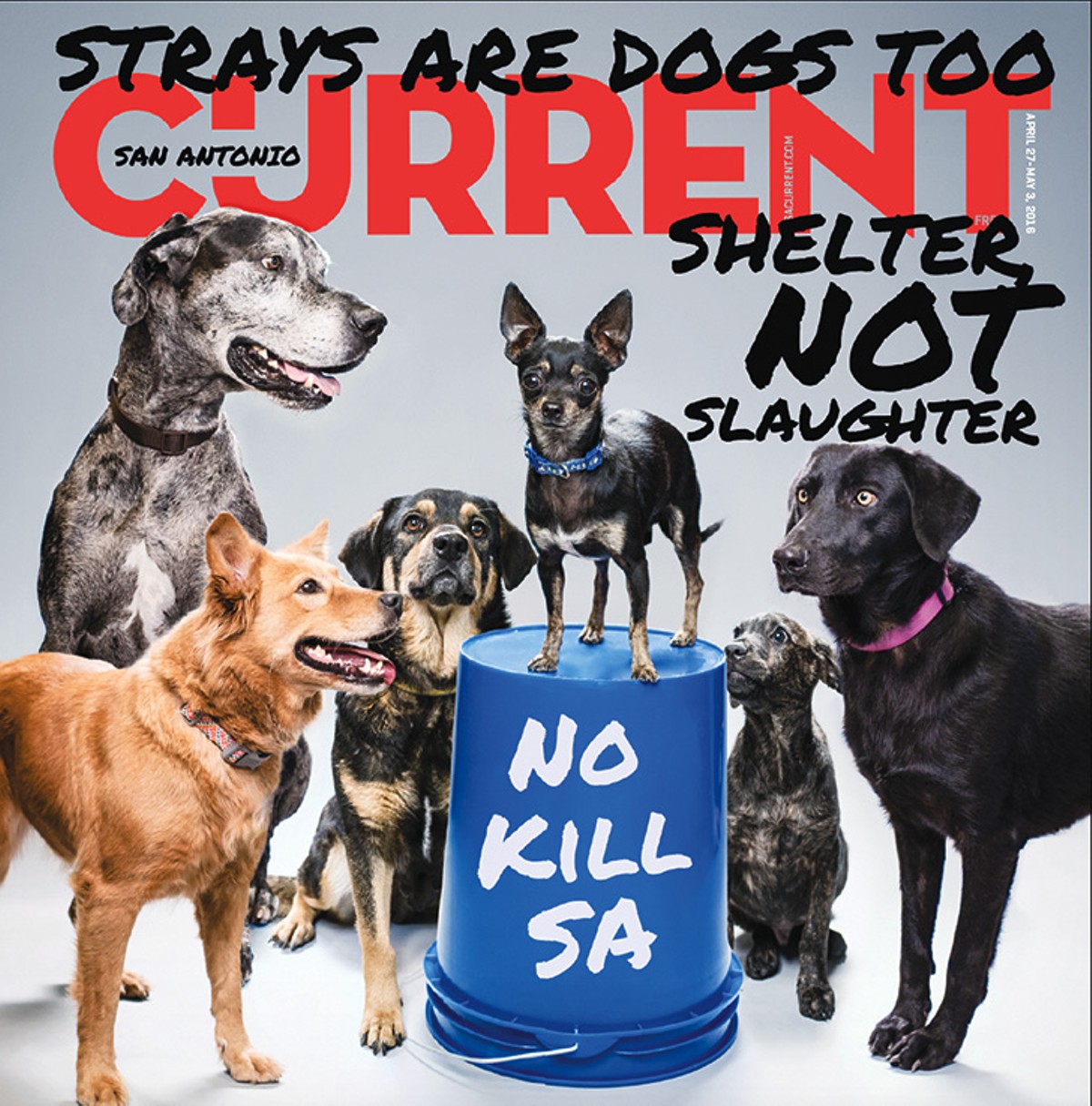

As 2015 closed, more than 9 out of every 10 dogs were being released from ACS care alive. The department stressed that reaching the threshold — generally accepted as the benchmark to be a "no-kill" shelter — was just another step on a long journey to spare and improve the lives of as many animals as possible.

The department spent millions of dollars over several years to change an operation which once killed over 70 percent of the animals that trotted or limped through its doors.

But despite the recent improvement in city shelters, neighborhoods are still plagued by dogs — both those that are allowed to roam freely by their owners and strays.

The attack on Abel Arias, 39, is an extreme example. He suffered "substantial injuries to his head, chest and arms" and "huge rips of muscle tissue to his arms and chest" before San Antonio Police Officer Matthew Belver arrived to help. Arias' condition stabilized after treatment at San Antonio Military Medical Center.

The mauling of Arias by dogs that an owner had let roam free underscored a tricky balancing act. As fewer animals die in San Antonio shelters than ever before, critics claim that strays and free-roaming dogs in some parts of the city — particularly poor neighborhoods — still pose a threat to public safety and health.

"The problem is severe," said Councilman Rey Saldaña. "Right now it's not as bad as it used to be, but it's not enough for me for it to 'not be as bad as it used to be.' I think we need to solve this."

Progress and an Old Problem

In fiscal year 2010, ACS euthanized about 75 percent of all the animals it took in. More than a third of those animals were healthy or had treatable conditions. They were killed because there was not enough space to house them, and no one adopted them before they were euthanized.

But last year the department euthanized fewer than 4,500 animals, about 15 percent of its total intake, while impounding more animals overall.

Although there isn't an official count of San Antonio's stray population, dog bites and dead animal pickups — the two main measurements for strays — are also down. Reported dog bites dropped about 30 percent from fiscal year 2010 to 2014.

Between fiscal year 2011 and 2015, ACS picked up almost 35 percent fewer dead animals. At the same time, the department has performed more spay and neuter surgeries and issued more citations and warnings.

But those figures are little consolation to people whose communities are still overrun with both strays and dogs permitted to roam freely by their owners.

Martha Banda, who lives in the Denver Heights neighborhood on the East Side, has been trying to solve the stray dog issue there by organizing neighbors, reaching out to local officials and taking matters into her own hands: She owns five dogs, four of which she took in directly from the street. She still sees plenty of strays in the neighborhood, though.

"There's only so much you can do," Banda said. "It reflects poorly on the neighborhood. So many of us are trying to take pride in our neighborhood, be responsible ... make a blighted neighborhood kind of revived. It takes away from that."

Walking through neighborhoods with free-roaming dogs can be particularly hazardous for children and elderly people. Dogs must be on a leash at all times in San Antonio unless confined to an owner's property.

"It is an overwhelming problem. And when you have packs of free-roaming dogs, that's a public health issue. People can't go out and walk. You can't let your kids go out on a bike," said Janice Darling, executive director of the Animal Defense League of Texas.

Free-roaming animals also impose considerable demands on public resources, due to the expense it takes to catch, care for and sterilize them.

The stray problem is nothing new — it's persisted for decades in some communities. Saldaña, who grew up on the South Side, didn't know that free-roaming dogs weren't the norm until he went to Stanford University in California.

"Folks just generally ignored the fact that the problem was so bad because it's always been part of the community to see a stray dog running around or a pack of dogs following a pack of students walking into school," Saldaña said.

The long-standing, deep-seated nature of the issue is one reason why it hasn't been resolved. Whereas ACS substantially boosted its live release rate in just a few years, the embedded cultural forces that create the stray problem make it tougher to fix.

But community members and national boosters are also quick to rally around the no-kill cause, according to Xavier Urrutia, an assistant city manager and interim ACS director.

"There's a public will behind trying to increase the live release rate. With that comes volunteers and additional resources," Urrutia said.

Some animal advocates, community members and elected officials are irked by the perception that problems in certain neighborhoods don't seem to carry as much weight as the live release rate.

"You can have a 90 percent live release rate which ... on paper looks fantastic, but if you're not addressing the issues in the community, what good is it doing?" said Kelly Walls, a long-time area animal advocate who works with Homeward Bound Dog Rescue.

Walls and others are also concerned that the fanfare surrounding no-kill could lead the community at large — particularly in more affluent parts of town, where strays are not a problem — to tune out other animal-related issues.

"By being obsessed with ... no-kill and then say 'Oh we've reached it,' they give a false impression to the whole city that 'Oh we don't have to worry anymore, we're no-kill,'" said John Bachman, the co-executive director of Voice for Animals.

Not One or the Other

Even though Bachman and others praise ACS for raising the live release rate, some question whether the 90-percent figure is completely accurate.

Advocates are concerned over whether certain dogs at the shelter deemed unhealthy, untreatable or aggressive — whose deaths don't count toward the live release rate, which only counts healthy, adoptable dogs — are mislabeled. Some claim that the dogs are just scared from the ordeal of being picked up and put in a new place, and that kennel workers misinterpret that as aggression.

They also cite ACS' slow response times in the field. Others claim that the "no-kill" label leads some who surrender their animals to believe that there's no risk of them dying. One local advocate, Cyndi Cox, sends out a weekly email blast showing adoptable dogs that were euthanized over the past seven days.

ACS officials defended their practices in determining whether a dog should be euthanized, and chalked up the department's responsiveness to a matter of finite resources.

"We received 107,000 calls for service last year. With 40 officers ... it's numerically impossible to bring all those animals in," said Shannon Sims, ACS field operations manager.

Claims of ACS cutting corners don't hold water with Saldaña, although he held them himself when he first took office.

"I was very skeptical that we could get to a successful live release rate while at the same time meet the needs of my constituents. ... For me it was a foregone conclusion that somehow the city would be fluffing its numbers to make it seem like we would be picking up more animals when really we weren't. ... But I just haven't seen those facts bear out," Saldaña said.

His colleague, District 2 Councilman Alan Warrick, supports increasing the live release rate, but he's wary of doing so at the expense of public safety.

"We've proven that we can do [no-kill]. But I think the key is really changing that and saying 'No strays first,'" Warrick said. "The vast majority [of no-kill activists] are in areas that don't have these kind of problems. ... It's a lot easier to say 'We shouldn't pick up these dogs' ... because their children are able to walk to school without carrying golf clubs or sticks to beat off the pit bulls."

But if the answer was just to pick up and euthanize every dog on the street if it wasn't quickly adopted, the problem may have been solved by now. That's the model that ACS followed closely for much of its history.

"The ... methodology the city had in place say, 10 years ago, which was to pick up every stray animal and basically that animal was euthanized at the end of the day. It did not deter the number of roaming dogs out there," Urrutia said.

The longterm solution, all agree, is to increase efforts surrounding education and sterilization. Although many factors play into the live release rate and stray dog population, Urrutia and Sims credit increased block-walking, emphasis on returning animals to their owners in the field and a city ordinance that required all pets to be micro-chipped with much of the progress.

Spaying and neutering as many animals as possible — stray or owned — is perhaps the most important factor to resolve the problem.

"The solution to the animal problem is to do a sufficient number of spay and neuter surgeries to reduce the birth rate down to a zero population growth. Until you do that, it's pure mathematics, you are not going to reduce the stray population," Bachman said. "Adoption is like treatment. You're treating the problem, but you're not solving the epidemic."

Bachman supports mandating spay or neuter surgeries, a move that many municipalities have already made, but that doesn't have the support of industry groups such as the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and the American Veterinary Medical Association. Deanna Lee, founder of Advocates for SA Pets, suggested at a recent ACS board meeting that a possible compromise would be to mandate spay or neuter surgeries for several years so that the city is able to temporarily slow the growth of the stray population.

And ultimately, if the strays continue to plague certain neighborhoods at their current levels, it will be difficult for ACS to maintain its high live release rate.

"The two need to work together. ... While there are dual missions, the approach is a comprehensive approach," Urrutia said. "It's not one over the other."