Chasing the Boundary: On Jerry Jeff Walker, Dad and Texas Transcendentalism

By James Courtney on Fri, Dec 12, 2014 at 12:02 pm

I don’t like to get all personal. While I accept and appreciate the fact that folks have intensely individual relationships to, and experiences with, music—the transcendental beauty in what Nietzsche called “The Gay Science,” lies in its universality and timelessness. That being said, my father didn’t raise a music critic or philosopher, he raised a man. And a man deserves to say what he damn well pleases, from time to time. So, here it goes.

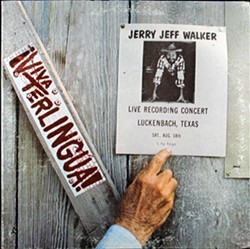

My dad, James Nuten Courtney, Jr., didn’t so much introduce me to Jerry Jeff Walker as leave him lying around for me to discover. Like clues to the core of my dad’s wild yet gentle soul, his old vinyl copies of Jerry Jeff Walker (1972), ¡Viva Terlingua! (1973) and The Best of Jerry Jeff Walker (1980) left a teenage me enraptured, imagining him, pre-kids, as a representative of, and participant in, a kind of freedom that had never even occurred to me before. This freedom, to exist beyond the bullshit boundaries of a society that measures value in terms of ‘usefulness,’ was something my dad never directly eluded to, but always struggled towards. And once I’d memorized the words of those shit-kickin’, drinking songs and sad, old ballads of the everyday, he and I would talk frequently about them and the endless blurry-happy memories which, for him, had become forever associated with them. Jerry Jeff was my way in—into my dad’s true nature, into the actual value of real human lives and stories, into the joy of imperfection, and ultimately, into the easygoing Texas Transcendentalism that still lies at the heart of my relationship to reality today.

On November 6, 2014, somewhere around 2pm, my dad—stuck in a fucking hospital bed—passed into the next world, after a short and futile battle with an aggressive form of lung cancer. As chance would have it, I secured an interview with Jerry Jeff, just nine days before dad's material liberation. We talked briefly about it, and a wave of deep satisfaction crossed his face, probably imagining the first chords of some too-long night in the foggy past. He grinned and said—his speech severely limited by a series of strokes—that the interview op was "Neat. Real neat." Which wasn't a snide dismissal, but, for him, a legitimate and longtime expression of being tickled, in the mystical sense.

Would I find, in conversing with this old roughneck troubadour, some sublime and wise sum of my father's existence? I was in that irrational, sorrow-plus-searching frame of mind when I called Jerry Jeff. Confiding in him my father's and my story, albeit in brief, I found a surreal personal catharsis and an immediate dissolution of the typical 'professional' tone of the interview.

“It’s nice to know that your music can become truly personal to people, that it might go into the fabric of some people. That’s one of the things about Texas. When people want to get away and relax and make their heads clear up, they can sit around a campfire and hear songs that matter to them,” he mused. He offered no ham-handed condolences, but opened up and talked freely with me about things dear to him. We agreed that, as Billy Joe Shaver told me earlier this year, music is a powerful (and cheap!) form of therapy. “But God knows Billy Joe needs it more than me,” he chuckled.

A few more topics came up and faded, as we shot the proverbial shit. Then I asked about how the hell he’d gotten started playing music and writing songs in the first place. Like so many things he told me that afternoon, the story seemed natural and pure and truly indicative of a man content to let the power of the moment lead him where it may, all the while holding on to his own center.

“In the 50s in New York, when I was in high school, we did a lot of playing Everly Brothers and stuff like that, that people could sing along with. And most of the time you could remember the chorus, but you couldn’t remember all of the verses. So I could make up the verses to get us to the chorus again. It was all very simple, but that’s where it started. Then, lyrics started to get more meaty when the whole folk music scene got going in the late 50s and early 60s. I liked the fact of the stories that these songs would tell. That gave me the idea that these songs would be more fun to learn and [with my guitar skills] these were more things I could actually play. The simplicity still stuck with me though. There’s a kind of enlightenment in finding simpler ways to say the basic truths. Then, as a solo singer-songwriter, I’d cover these folk songs and start slipping in a few of my own.”

It was “a little while later” when he first got his stage name Jerry Jeff Walker—he was born Ronald Clyde Crosby. He got a job as a bartender in New Orleans using a fake ID with the name Jerry Farris on it. Later, when the owner asked him to play some songs to help entertain the patrons, and when he eventually started busking on the streets, he wanted to call himself Jeff Walker. People, however, had already begun to know him as Jeff. “So it was like, you can be Jerry Walker or Jerry Jeff Walker, but you can’t be just Jeff Walker. So I said 'OK, I’ll be Jerry Jeff Walker.' It's just another one of those things where you’re trying to take some control and there really is no control. And it’s just a name anyway,” he reflected, with an almost audible shrug of his shoulders.

Of his subsequent move to Austin and the musical growth that happened there, Jerry Jeff started to get to that philosophical place that I came into the interview hoping we’d get to.

“I was looking for a scene that I could be comfortable in and do my thing and it turned out that Austin was that place. Texans like to have their lives sung about and I liked to write stories, songs about how we were living, so it just worked out. A lot of people say I just came and looked at Texas and sang it back to itself. Sometimes you can dig into a scene and really see it better when you’re not in it. Anyway, it was good to be in a place where a guitar could be thought of as a way of life and not just a phase you’re going through. It’s just not like that everywhere.”

KEEP SA CURRENT!

Since 1986, the SA Current has served as the free, independent voice of San Antonio, and we want to keep it that way.

Becoming an SA Current Supporter for as little as $5 a month allows us to continue offering readers access to our coverage of local news, food, nightlife, events, and culture with no paywalls.

Scroll to read more Music Stories & Interviews articles

Newsletters

Join SA Current Newsletters

Subscribe now to get the latest news delivered right to your inbox.