The music’s roots run deep in San Antonio, all the way back to the Czech-German dance bands of the late 19th century. To be sure, a staggering number of the greats have called our city home: Jimmie Rodgers, the Carter Family, Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash, Johnny Bush, Adolf Hofner and Ernest Tubb, to name a few.

“The history of country music in San Antonio is pretty much the history of country music,” said retired Express-News music columnist Jim Beal Jr.

That solid foundation has allowed country music, in its original form and its many offshoots, to thrive here. The recent opening of the Lonesome Rose, for example, and the international success of modern-day cosmic cowboy Garrett T. Capps attest to the enduring appeal of the genre — and to SA’s central place in it.

To understand the significance of San Antonio in the development of country music, it helps to examine the genre’s origins. Though later lumped together, country and Western originated as two distinct genres, with country representing a cleaner, commercial version of Appalachian folk, while Western music took in a wider variety of influences. Alan Lomax documented the form in his 1910 book Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads.

Western music, also called cowboy music and Texas music, fused many influences — including country, blues, jazz and conjunto — into a new form, and that diversity is its most salient feature. As a crossroads city, San Antonio has always effortlessly combined musical forms. Of particular relevance, and easy to forget when surveying modern country, is cowboy music’s Mexican influence. And, of course, there were other shaping factors.

“Why is country music so strong in San Antonio? Well, our city has had a lot of country songs written about it, for starters,” said Hank Harrison, a bluegrass bandleader and host of the KSYM show “Hillbilly Hit Parade.” “You’ve also got a great bunch of fans here. People here know how to dance. Plus, the military presence created military jazz bands, and those jazz players feed into every scene and make everything better.”

Royal lineage

“Red River” Dave McEnery was one of the city’s earliest cowboy song heroes. After attending Brackenridge High School, McEnery rode the rails around the country and earned money as migrant worker and traveling singer.

His biggest hit, “Amelia Earhart’s Last Flight,” was also the first commercial country music TV broadcast, performed live at the 1939 World’s Fair. In one memorable stunt, the legendarily prolific McEnery was handcuffed to a piano at local radio station WOAI, where he wrote 52 songs in an eight-hour period.

In addition to writing the fascinating and still-relevant tune “Shame is the Middle Name of Exxon,” he penned the dark and bizarre ballad “The California Hippy Murders” about the Manson Family. McEnery also starred in films and hosted radio programs on WOAI and the legendary XERA/XERF, a 185,000-watt “border blast” radio station broadcasting from Acuna, Mexico.

Station owner Dr. John Romulus Brinkley lost his American radio license after grafting goat testicles into the genitalia of middle-aged men eager to reclaim their youthful virility. The power of the goat testes may have been phony, but it earned the physician real money. He pumped his millions into the station that became known as the X, which reached millions of American homes and made the Carter Family into country music’s first superstars. Indeed, the revered musical family lived in San Antonio to be in closer proximity to the station, where they performed twice weekly.

Country icon Johnny Cash later married June Carter of the group. But that’s not his only SA connection. The iconic singer-songwriter was stationed at Lackland and Brooks AFBs in 1950. While here, Cash met Vivian Liberto, his first wife, although his drug use and infidelity led to a 1966 divorce.

Jimmie Rodgers, often called the father of country music, also found his way to San Antonio.

Rodgers was known for elevating so-called “hillbilly” music by fusing it with elements of jazz and blues. His railman persona and songs captured the imagination of America, making him the first person inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame.

As Rodgers finished his career as a resident of Alamo Heights, Ernest Tubb was just starting. In the ’40s and ’50s, Tubb’s tailored suits and ten-gallon hats helped elevate the genre’s hillbilly image, while his use of electric guitars helped define Texas honky tonk.

As a teen, Tubb worked as a San Antonio soda jerk, taught himself the guitar and landed an unpaid job at local radio station KONO. He rode his bicycle to the station, guitar strapped across his back, for live performances.

Rodgers’ widow heard those broadcasts. She took him under her wing and guided him towards stardom. Later, he returned the favor for other young performers, including Hank Williams and Loretta Lynn.

Bandleaders and songwriters

Equally important to San Antonio’s evolution into a country music mecca was Adolf Hofner, a renowned bandleader who, alongside Bob Wills and Milton Brown, popularized Western swing. Born to Czech and German immigrant parents, Hofner sang songs in Czech and recorded for the legendary Okeh label. He was later sponsored by Pearl beer, after whom he named his band, the Pearl Wranglers.

Even the Texas Top Hands, Texas’ oldest continuously performing band, started in San Antonio. The group, founded in 1941, still gigs to this day, proudly carrying the torch for the Western swing subgenre. Its tour bus sat parked at Austin’s Broken Spoke for decades.

The Top Hands performed at the first San Antonio Rodeo and eventually became Hank Williams’ backing band on his fateful last tour. After playing San Antonio venue The Barn, Williams, then sick and drunk, played his final show at Austin’s Skyline Club.

The Top Hands aren’t Williams’ sole San Antonio connection. The country legend’s signature song “Lost Highway” was penned by Leon Payne, a San Antonio resident known as “the Blind Balladeer.” Payne wrote songs covered by Elvis Presley, Dean Martin and George Jones, and his “I Love You Because” and “You’ve Still Got a Place in My Heart” transcended the country genre to become entries into the Great American Songbook.

Though not originally from the Alamo City, Bush moved here in 1952 and dove headfirst into the rough-and-tumble dancehall scene with a regular gig at the Texas Star Inn on Bandera Road.

“You had to do the standards that filled the dance floor ... back in those days, you had to keep the music going, because if you didn’t, they’d fight,” Bush said in 2002.

Dancehall days

In the music’s heyday, Texas’ innumerable dancehalls helped foster the burgeoning country scene. Those venues became the petri dish from which the culture grew.

Dozens of dancehalls dotted San Antonio during those early days. Weekend partiers could trek across town, heading from the Farmer’s Daughter on W.W. White Road to Randy’s Rodeo on Bandera Road to the Texas Star Inn, also on Bandera, to Floore’s Country Store in Helotes and end up in Bandera at Arkey Blue’s Silver Dollar, the state’s oldest continuously operating honky tonk.

“In country music, the way you tell if you’re going over is if the dancefloor is full,” music writer Beal said. “The Farmer’s Daughter, that was hardcore Bob Wills-type stuff. It was my favorite spot. The dancing was incredible there, and it was all ages. It was a family thing.”

The dancehall period was widely considered a golden era for country music, helping make it “America’s music.”

The records also grew in popularity due to the Nashville sound, pioneered by Chet Atkins and others, which used strings and choirs to create a lush backdrop for singers. As country songs became more profitable, it also became smoother and more polished, sounding more like pop and less like the genre’s roots.

But not for long. And that brings us back to San Antonio.

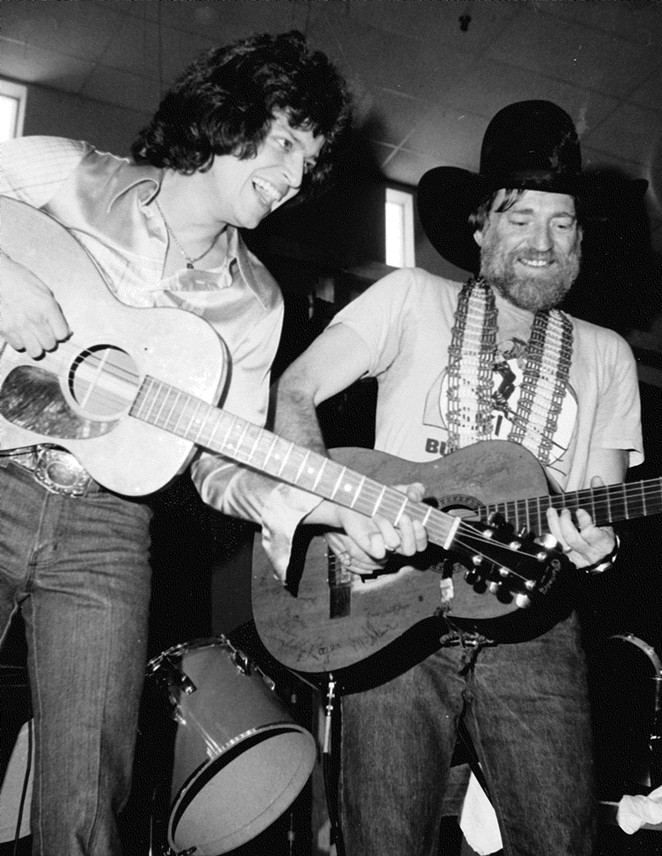

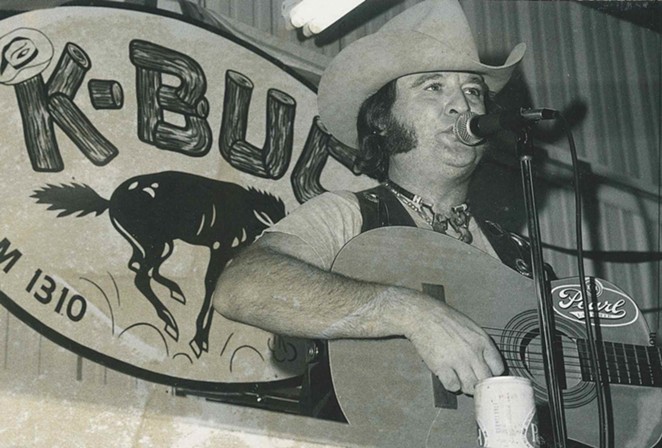

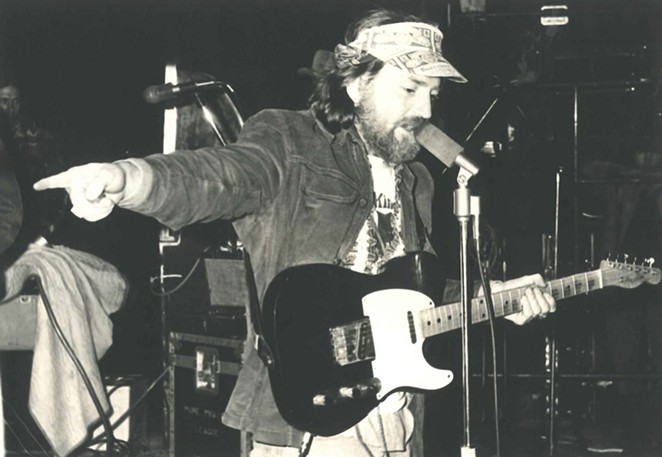

Eager to escape that slick sound, Nashville songwriter Willie Nelson moved to a ranch near Bandera and started a weekly residency at Floore’s Country Store. The Texas native’s return and his several-year stint at Floore’s culminated in his legendary 1972 Dripping Springs Reunion and the following year’s Fourth of July picnic, a blast that unofficially launched the progressive country movement, later known as outlaw country.

That scene created a constellation of stars: Jerry Jeff Walker, B.W. Stevenson, Michael Martin Murphey, Willis Alan Ramsay and Waylon Jennings. Their music was still country, but with less polish, less production and a lot more attitude.

Venues popped up all across San Antonio catering to the new music. During the 1970s, the city gave rise to the Bijou, the Golden Stallion, the Bits and Pieces and the Longneck, part-owned by San Antonio music legend Augie Meyers.

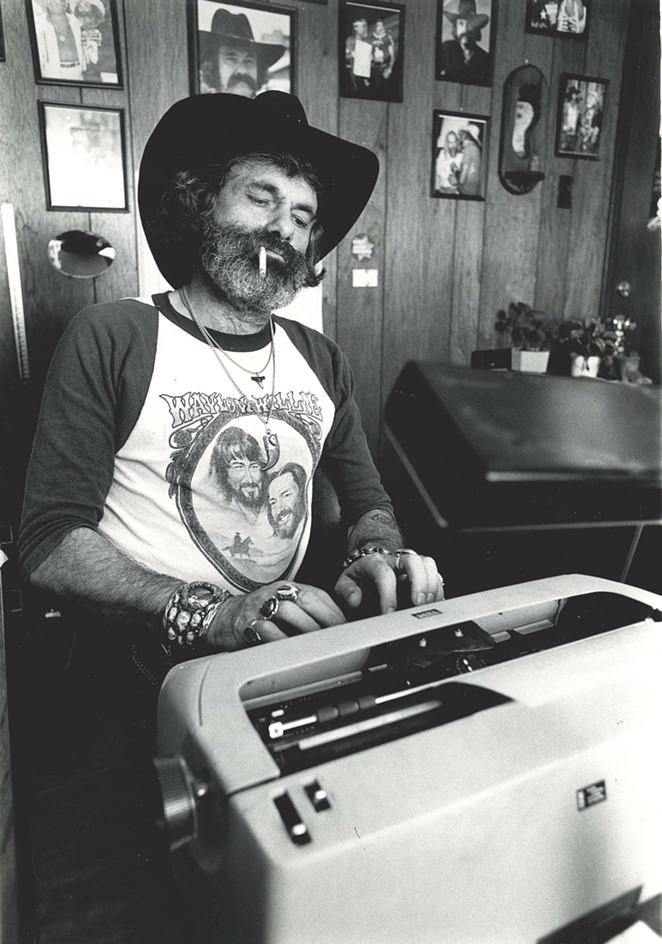

And there to document it all was legendary SA journalist Sam Kindrick, whose Action Magazine, launched in 1975, became a chief documenter of the emerging outlaw scene. His humor and attitude have both charmed and vexed readers and adversaries for decades.

“Sam Kindrick has done more than any single person over the last 60 years to document music and entertainment in San Antonio,” Joe Nick Patoski, the dean of Texas music journalism, said in an article published by Texas State University’s Wittliff Collections.

Originally an Express-News columnist, Kindrick was fired for drunkenness and consorting with “undesirable types.” Among these undesirables was his close friend Willie Nelson.

“First time I met Willie, he was smoking dope under a mesquite tree out at Floore’s,” Kindrick recalls. “He later played me a cassette of the Red Headed Stranger before its release. I told him I didn’t think it’d catch on.”

Kendrick went on to emcee two of Willie Nelson’s legendary Fourth of July picnics, and started Action Magazine at the singer’s urging. The entertainment newspaper’s guest contributors included one who went by “Biscuit Wheels” and another writing from the Bexar County jail simply known as “Doc.”

Kendrick credits the Medellin family and their San Antonio Press for carrying him through several rough patches.

“Action wasn’t a music magazine,” Kindrick said. “It just covered the outsized personalities all around me.”

Beyond Nelson, Ramsay and Bush, those included David Alan Coe, Leon Russell, Spanky McFarlane and innumerable greats. Though ostensibly a chronicler of outsized personalities, few were larger than Kindrick himself.

His stories are voluminous and hilarious, like the time he finagled a role in Steven Spielberg’s first film The Sugarland Express, shot in the San Antonio area during the early ’70s. “Goldie Hawn was a complete pothead,” Kindrick said.

Another time, Kindrick lured Jimmy Buffet to San Antonio honky tonk The Longneck.

“I told him, ‘I’ll give you $500 and all the coke you can snort.’ And he came down and played,” the journalist recalls. “Packed the joint.”

Kindrick was no stranger to substance abuse himself. His cocaine use and that of Nelson’s road crew reached such proportions that it became grounds for termination. “If you’re wired, you’re fired,” read signs posted on the singer’s tour bus.

Excess ultimately caught up with Kindrick, and he served time in jail. His arrest, splashed across the front pages of SA newspapers, proved to be the wake-up call he needed.

“I’ve been sober since 1989,” said Kindrick, now 82 and still sharp as a tack.

Rocking the country

As progressive country took hold, a parallel strain of roots music emerged from the rock scene and hippie subculture. The psychedelic scene induced a whiplash counterreaction from hippies burnt out on light shows, paisley and feigned interest in the sitar.

Inspired by the Band’s Music from Big Pink and the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo, hip kids embraced stripped-down music that embraced its American roots. That hippy folk scene gave rise to some of the era’s great country songwriters, and while still a teenager, San Antonio’s Will Beeley was there to witness it all.

“There was a coffeehouse downtown called the Gatehouse. Another spot by San Antonio College called Doogie’s,” Beely said. “I was 15 and not allowed in, but I’d sneak in the back door, and I saw some amazing folks: Townes Van Zandt, Bill Moss, Don Sanders, Rex Foster, Cassell Webb, Marylou Weaver. Such amazing talent. I got to be the guy who’d play three songs between the acts. I learned a lot.”

Beeley recorded two classic alt-country albums — Gallivantin’ and Passing Dream — in the ’70s, but by the ’80s, frustrated by lack of success, he became a long-haul truck driver.

The albums were too good to languish in obscurity though, and eventually were reissued by the influential Tompkins Square record label. Beeley has since experienced a rediscovery. He was an outlier for what would later be called “Americana,” a melding of progressive country and hippie folk.

“The country people called us hippies,” he said. “That changed in the late ’70s, going in to the ’80s.”

Steve Earle, an eventual pioneer of the Americana scene, was also a character from the Gatehouse and a close friend to Beeley. Now one of the genre’s top acts, Earle learned his craft in San Antonio folk clubs as a teenager. He also got involved in the anti-war movement, performing Country Joe’s “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag” on a flatbed truck during a demonstration in front of the Alamo.

“My dad, who’s an air traffic controller and worked for the government, got in trouble,” Earle recalled in a 2019 interview with Beeley.

Roots outliers

Earle wasn’t the only Americana outlier to emerge from San Antonio’s music scene.

As a member of the ’60s psych group the Children, Cassell Webb recorded the lost psych classic Rebirth but went on to become a female voice in the emerging outsider country scene. Her short-lived project with Red Crayola frontman Mayo Thompson called Saddlesore produced one essential single “Old Tom Clark” in 1970, which was rereleased in 1994 by Chicago’s influential Drag City label.

Subsequently, Webb performed with Jerry Jeff Walker, Willie Nelson and B.W. Stevenson, before marrying renowned punk producer Craig Leon, whose credits include the Ramones, Blondie and Suicide. She reunited the Sir Douglas Quintet for their 1981 album Border Wave, produced albums by legendary English post-punks The Fall and continued to record on her own.

Like Webb, Gatehouse regular Rex Foster connected the counterculture to the emerging roots movement. The musician joined the legendary traveling concert-turned-film The Medicine Ball Caravan — touted as “Woodstock on Wheels” — then settling in France to record the album Roads of Tomorrow, a lost precursor to the alt-country movement.

The fabled Blaze Foley grew up in San Antonio under his real name, Michael David Fuller, and performed gospel tunes with his family. After living on a Tennessee commune, he returned to Texas with a new moniker and a head full of wonderfully evocative songs that continue to influence artists today.

Then of course there’s Doug Sahm, whom the New York Times dubbed the “patriarch of Texas rock and country music.” The San Antonio native played steel guitar with Hank Williams and was offered a spot on the Grand Ole Opry at age 13, although his mother declined on his behalf. He even learned fiddle from J. R. Chatwell, a member of Adolf Hofner’s band.

Sahm eventually left for the San Francisco scene after a 1966 drug bust. While there, he charted a Billboard hit with “Mendocino” and graced the cover of Rolling Stone twice. His eventual return to San Antonio didn’t last long, however. He was reportedly beaten up by Balcones Heights policemen displeased with his California license plate.

Sahm left for Austin soon thereafter.

Commercial turn

By the time the ’70s closed out, however, country music changed, becoming more commercial. That focus on accessibility over authenticity increased with each subsequent decade.

“We old timers ... we got irate when we heard the shit they started putting out. It became pop,” Action’s Kindrick said. “Garth Brooks should’ve been hung by his heels. Him and Chris Gaines. Not that I feel that strongly about it.”

Texas’ dancehall culture, while still present, faded as time wore on. Its undoing?

“Netflix,” said SA bandleader Geronimo Trevino III, the author of Dance Halls and Last Calls, an indispensable book on the era. “Also, natural disasters, tornadoes, and even foul play.”

More than anything, though, stringent drunk driving laws ended the phenomenon, Trevino explained.

“Folks got scared to take a chance out on the highway,” he said. “Back in the old days, that was less of a concern. And the old dance halls, folks brought their kids, no problem. It was a family event. But now you can’t really do that as much. It’s stricter with the kids being around alcohol.”

Despite the dearth of dancehalls, the music lives on. Some of the older venues remain and real-deal country continues to expand and thrive, observers say.

“Everybody always talks about the good old days,” Kindrick muses. “Today will be the good old days to somebody, someday. ‘I remember when,’ they’ll say. It’s all just ... evolving.”

To his point, Floore’s Country Store has continued to bring in the crowds by expanding their booking from strictly country to all things Americana.

“It remains vital. It’s the same kind of thing, it’s just they’re booking music of now, not the music of the ’40s,” former Express-News writer Beal said.

Indeed, Americana has emerged as a thriving genre nationwide, with recent converts including Robert Plant, the famed Led Zeppelin singer.

San Antonio Rose

Meanwhile, St. Mary’s Strip honky tonk the Lonesome Rose has brought live country and roots music back to the city center. Venue co-owner Garrett T. Capps, a performer who’s emerged as a formidable country ambassador, explained the appeal.

“I would like to think that we’re picking up a legacy,” he said. “Our dream for this place is, when you open the door, it’s this hotbox of energy with folks dancing.”

Of course, recent spillover from Austin hasn’t hurt. The rising costs of living in the city once branded the “Live Music Capital of the World” has driven out performers who can no longer afford to call it home.

“They’ve obviously overshadowed us in the alt-country world, but things have been changing recently,” Capps added. “It’s hard to find a working-class musician who lives there anymore. It’s too expensive.”

Larger venues like Cowboys Dancehall and even the AT&T Center cater to the more polished commercial country sound, and of course San Antonio still lays claim to country mega-star George Strait, but even the country genre itself seems to be experiencing an upheaval with the genre-bending moves of rapper Lil Nas X.

“Commercial country does well here, and it fills the AT&T Center, but nobody dances in there,” Beal says. “Everybody’s sitting and listening. But there are dancehalls that are still kicking, and dancing is still a crucial part of it.”

Martinez Hall, for example, still provides the same program as it did nearly 100 years ago, the music writer points out. And it still makes folks dance.

“They book Czech and Polish bands and then country two-step,” Beal added. “The same kind of stuff Adolf Hofner was doing.”

To be sure, plenty of San Antonio artists are still holding down the old way. Foremost of those might be Billy Mata and the Texas Tradition, a heritage-minded band that’s racked up awards from the Academy of Western Artists and praise from old-school honky tonkers and the press alike.

But for some, it’s exciting to see bands coming up in San Antonio that can write new chapters for the music while avoiding mass-produced Nashville sheen.

The Last Bandoleros, for example, are reclaiming the genre’s aforementioned Hispanic roots. Currently signed to Warner Nashville, the band toured with Sting and were praised by Rolling Stone as 2018’s “most important new country band.”

The act’s fusion of country, rock and conjunto may be what brings the story full circle.

“You never know when something else is gonna come out,” Action Magazine’s Kindrick. “You never know when somebody is gonna come out and revolutionize the whole thing. There may be another Willie Nelson out there, in another form, with another twist on the music.”

To listen to an online sampler of San Antonio country favorites, visit this Mixcloud playlist.

The playlist includes:

- Willie Nelson "Good Hearted Woman" (Live at Floore's Country Store)

- George Chambers "Dim Lights, Thick Smoke and Loud Music"

- Doug Sahm "Be Real"

- Leon Payne "I Love You Because"

- Adolf Hofner and his San Antonians "South Texas Swing"

- Mother Maybelle Carter "Wildwood Flower"

- Johnny Bush "Green Snakes on the Ceiling"

- Adolf Hofner and the Pearl Wranglers "I Get So Lonesome (Since You're Gone)"

- Slim Roberts "Lonesome Old World"

- Texas Top Hands "You're Killin' Me"

- Adolf Hofner "Shiner Song (Farewell to Prague)"

- Jimmie Rodgers "T for Texas"

- Leon Payne "Lost Highway"

- Ernest Tubb "Drivin' Nails in My Coffin"

- Charley Pride "Is Anybody Goin' to San Antone"

- Moe Bandy "I Just Started Hating Cheating Songs Today"

- Rex Foster "In the Spring"

- Texas Tophands "You Can't Have Your Cake and Eat it Too"

- Garrett T. Capps "Sunday Sun"

- Johnny Bush "Whiskey River"

- Augie Meyers "Memories" (Live at the Longneck)

- Blaze Foley "Clay Pigeons"

- Will Beeley "Sailing with You"

- Saddlesore (feat. Cassell Webb) "Old Tom Clark"

- Steve Earle "The Graveyard Shift"

- The Last Bandoleros "Where Do You Go?"