It was the first electricity-rate increase our homegrown utility had sought in more than 15 years — a paltry $6 per average monthly bill, CPS Energy officials projected. Despite being cajoled by Mayor Phil Hardberger to rally to CPS’s aid, the majority of San Antonio’s elected leaders balked.

Instead, they offered the utility a dose of public humiliation with a lesser 3.5-percent rate hike, and deferred implementation until after the peak temps of this summer have passed.

For that, the San Antonio Express-News editorial board called the rebels out by name and accused them of a “shortsighted populist gesture” while lauding CPS as “one of the best-run power companies in the United States.”

Ultimately, the whole fiasco made no nevermind to CPS. They’ve set about making up the lost revenue by levying hefty gas and electricity fuel “adjustments” of about 90 cents per 100 cubic feet of gas and 2 to 3 cents per kilowatt hour of electricity. For one $300 electric bill, the adjustment alone tacked on $100.

This spring’s rate-hearing exercise had some unintended benefits, however. By putting CPS’s top personnel on the stand, so to speak, it wormed out some interesting admissions from the notoriously tight-lipped utility. Perhaps the worst brag that Steven Bartley, executive VP over communications, and CEO Milton Lee made had to do with the utility’s declining workforce. The pair painted the loss of 500 employees over the past five years as a badge of fiscal discipline. But if one looks critically at that claim (and there is no sign that any on the Council have), one quickly finds the true price of the “re-org.” It’s taken out in crippled safety standards, lost morale, and legal fees. Interviews with dozens of current and former CPS employees, and a review of court dockets filling up with race-, gender-, and age-based discrimination lawsuits, suggest staffing changes have been ugly and forced.

San Antonio attorney Alex Katzman is handling more than 25 discrimination suits against CPS. “This is across the board: sexual harassment, age, gender, race, but I’m only handling employment-related cases. As a governmental entity, they have a lot of immunities.”

Since CPS is municipally owned, it falls outside the scope of OSHA and other federal protections. Most of Katzman’s cases are based on the company’s failure to address employee complaints in a timely manner.

“CPS is slow to respond to employee’s allegations,” he said. “I think there’s a culture where complaints of harassment and discrimination just aren’t dealt with promptly and they’re not dealt with fairly.”

From a public-safety perspective, one of the most disturbing shifts within CPS has been the restructuring of frontline service workers and changes in its mapping department. Because of reorganization, outsourcing, a few key outside hires, and goosed software upgrades, huge portions of the city’s electrical grid are simply not in the utility’s online system. Mapping-department employees say they are more than a year behind in getting network changes into the system even as the city grows by thousands of new residents each month.

A failed transmission line in February led to a blackout in the Medical District that left several San Antonio hospitals and treatment centers either in the dark or pulling on backup-generator power. It was the sort of failure that shouldn’t have lasted for more than an hour, according to CPS linemen who responded to the event. Instead it rattled on well over three hours and took a full two days for CPS to complete the repair.

Those I spoke with blamed internal reorganization that took the most skilled employees — four switchmen personally tasked with protecting the hospital district, military bases, and airport — and required they join the cross-training ranks in what essentially was a demotion intended to diffuse their experience across the ranks.

One former switchman with 30 years experience inside CPS explained it this way: “Linework is a craft that, to be adequately trained and skilled, it’s something you have to do every day. Every day. You don’t have room to do line work on a line crew for a couple of months and then come off and go into the underground bunch and do a little cable work underground, and then come out of there and go do some service and meter work, and then maybe eight months to a year come back to linework. That’s what they’ve done, and the quality of linework has gone down. The incidence of accidents have gone up. The incidence of outages to the customers caused by some kind of failure on a line crew’s part has gone up.”

During the 3 a.m. Medical Center outage, an underground repair crew was tasked with restoring power to the cluster of facilities that included the VA Hospital, Physicians Plaza One and Two, and Methodist Specialty and Transplant Hospital. But after an hour of no progress, frantic calls were being made to a former switchman who had since stepped down to the ranks of “troubleshooter.” At first, the embittered employee, who was not on call that night, refused to respond. Gradually, his conscience began to wear on him.

“At first, I not only told them no, but hell no. Then I got to thinking, ‘I can’t do that.’ That’s not the way I was brought up. I take pride in my work. I told them, ‘OK. What circuit is out?’”

It was the 754. In less than 30 minutes the former switchman was on the scene and power was being diverted to a second line, restoring the majority of the lost load before the underground crew met him on his rounds to the various

transformers.

For many of these facilities, there are no alternatives to CPS cables and lines.

“There’s a huge cluster that has no generator backup, and when they’re down, they’re down till someone gets there to physically isolate the cable that has failed and then switched to their alternate feed,” said one lineman.

An entire section of faulty cable had to be removed and replaced. “By the time he came in and did everything, three hours had passed by,” another lineman familiar with the event told me. It was not a repair job for the record books.

Another outage, a downed power line taking out San Antonio International Airport, offered the perfect training ground for newbies undergoing cross-training. The airport even offered to pay the overtime to make it happen, but CPS management chose instead to send staff home, several responders say.

Worse, the pole that caused the outage had been inspected by contract workers just a few months before the event. Would it have mattered if the pole had been “tagged” as needing replacement? Probably not. Several linemen insist that budget considerations have drastically reduced the number of poles being replaced this year. Linemen worry that reduced pole replacement coupled with a halted tree-trimming program mean more problems are on the way.

Each of the three regional CPS service centers — northwest, southwest, and east — are running low on capital infrastructure, must-haves like high-voltage wire, transformers, poles, and conductors, several linemen say. That shortage would delay repairs in any major outage.

Many are already afraid to respond to even so-called minor emergencies because of the reorganization. Linemen are “scared of who they may be working with,” another tells me. “That’s one reason they were having a problem having people respond to storms.”

Consider it the ascendance of the corporate mind over public service.

SA attorney and labor champion David Van Os is representing the International Brotherhood of Electric Workers in two recently filed lawsuits: one submitted in December 2007 for “fostering a hostile work environment”; the other, filed this month, alleges illegal wiretapping of a meeting between CPS officials and IBEW reps.

Van Os said the most disheartening thing he has seen happening within CPS over the past few years has been the “adoption of a cutthroat corporate mentality with senior managers and some mid-level managers, and first-level managers treating the workers in the manner of the very worst of the new Gilded Age corporate mentality. They’re treating the workers as data bits rather than as people.”

IBEW International Rep Ralph Merriweather and others in the union are convinced that CPS managers are intentionally sabotaging the utility to sell it off to the deregulated market. “We feel they have purposely implemented all these things, made the jobs so unbearable, customer service so low, that citizens will demand privatization,” Merriweather said. “We’ve had an `union` agreement here for 97 years. Right now, they’re not responding to anything we do.”

The IBEW sought for months to negotiate with CPS before filing its first lawsuit, Merriweather says. Though there has been at least one significant meeting between CEO Lee and Merriweather in recent weeks, for the most part CPS’s upper management have circled their wagons and refused to budge. As of press time, CPS officials had not made themselves available for this story `See “Damage Control,” Page 16`.

“Don’t call me at work. They record our conversations.”

That’s how a typical conversation closes with those in mid-level management at CPS Energy.

The cell is fine, the man tells me, before the nearly universal CPS-employee interview parting: “You’re not going to use my name, are you?”

I’ve gotten the same treatment from the 20-some CPS Energy employees I’ve met with these past several weeks. They’re scared of retaliation, but they’re more scared of what’s happening at the shop; so they speak to me, on background.

While CPS has neither confirmed nor denied the charges against it, with this many employees across a range of departments expressing the same concerns found in a wide-ranging, published employee survey and a variety of lawsuits, there’s likely something there worth listening to.

One of the most terrifying of the many recent internal changes is the apparent meltdown within CPS’s mapping department. Staff there is engaged in a multi-year changeover from a graphics-based computer-mapping system to a more interactive network with GIS elements. Thanks to staff reductions, they are more than a year behind schedule. That means that any changes or additions made on the electric grid during the last 12-18 months simply don’t show up on the handheld devices the linemen rely on, or on the computer screens referenced by the systems operators overseeing them. This fact was confirmed by a variety of employees in the mapping department, the service centers, and at systems operations. The faulty maps also mean that in many cases what linemen and repair crews are visually looking at on the ground is not what their overseers at the operations center are seeing on their computer screens.

Even though several mapping-department employees have been at the work so long that they helped convert utility paper maps into the first computerized systems during the 1980s, they were not asked to join the core group of decision-makers.

“For us, it was painful, because we were seeing they were making a lot of mistakes. But they didn’t want us to be part of that,” says one mapping employee. “More than anything it was an ego thing.”

“If you butted heads with `the team leader`, next thing you knew you were off the project. He just built his core team with only yes-men,” another said.

In about 2002, rumors began to circulate that a flurry of pink slips was about to blow through the department. That’s when many joined the IBEW for the first time. A new manager was brought in from Bexar County Appraisal District and tasked with “shaking things up,” staff say. Predictably, department employment began to decline — from the low 20s to about 17 today, I’m told. With the computer transition ongoing, paperwork was backing up.

In an attempt to catch up, much of that paperwork was shipped to subcontractors in India. Even after the new system went online, problems in the paperwork produced in-house and in India meant the pace of entry remained stiflingly slow.

The new system being used is more than a map in the traditional sense. It also attempts to mimic the way electricity flows in the real world, the way Simms-type software does with other elements of human infrastructure.

“If it doesn’t work out in the field, it doesn’t work on the map. If you try to put something that would electrically blow something up out here, it should tell you, ‘Boop. No. You can’t do that. It electrically doesn’t make any sense,’” one mapping employee said.

Such fail-safes are intended to limit human error.

“Every type of facilities-management software has fail-safes built into it. For example, it won’t let you put duplicates in. It won’t let you tie a 13 KV `electrical line` to a 35 KV `electrical line` without some device between them. It has specific rules that it has to follow,” he continued.

Unfortunately, the quality of the paperwork was so poor that management allegedly chose to disable those fail-safes to allow the updating of the system. “In order for them to get their garbage data into the new system they turned a lot of those off. They requested that the software company that they bought the software from turn it off so they could get everything shoved in there and say, ‘OK, we’re done.’ So now we’re dealing with all those issues and they wonder why linemen are going out there and virtually being electrocuted, because everything’s messed up. The maps that they are getting are not accurate.”

This is confirmed by a source of the first caliber: a systems operator working in CPS’s control center with 25 years under his belt.

“Somebody’s going to go out there and get killed,” the systems operator said bluntly. “I already told them, I’m not going to sit there and take the rap for it.”

On the front line it works like this:

The systems operator gets a report that a circuit has failed — maybe power’s gone out in your subdivision. He sends a line crew or troubleshooter to check it out, but what they find doesn’t gel with what their handheld devices say should be there.

They call back to the systems operator and report: “Yeah I’m here and I’ve got this three-phase conductor down at this location.”

“Well, hold on,” the SO reports back, “I don’t show it here.”

So you have a dead circuit. A crew that has no idea where the line’s at. The lineman spots a switch that theoretically could close the circuit. He checks his handheld. The handheld spits back: “No Switch Found.”

Even the control center screens are drawing a blank.

“We’re not getting the right information,” the systems operator said. “I’ve got guys calling me in here and we can’t even see where they’re at. We can’t spot ’em. We have to ask, ‘Do you have a switch? Do you have a device? Do you have an address or location?’ to try to pinpoint where `they’re` at, because the map is not up to date.”

That’s not the way it’s supposed to work. Generally, in an outage, the control center monitoring the electrical network would be able look and see where switches should be opened or closed to fix the outage, or if they need to shift the load a certain direction. “We don’t have a clue to what’s right. We just hope nobody gets killed,” the operator said.

Like the linemen interviewed, the mapping employees say they are terrified of the potential ramifications of what is happening in their department.

“We’re scared to death. We know all that’s going on. We don’t want to be held liable for the process that’s going on now,” he tells me. “In six months to a year, they won’t be able to hide it.”

In mid-April, the IBEW Local 500 leadership approached City leaders with their concerns in a five-page letter. Inside, Local President Gary Kirby asked 35 questions about conditions at CPS before calling for the resignation of CEO Lee, Vice President of Energy Delivery Alfonso Lujan, Vice President and Chief Administrative Officer Paula Gold-Williams, and “any other management officials who are destroying the integrity, respect and trust of the citizens/employees of CPS Energy.” The union included the workplace survey.

Two weeks later, Kirby wrote to the members of the Board of Trustees asking for a hearing so the Board could listen to employees directly. No response.

Two weeks after that, International IBEW Rep Merriweather wrote back to Mayor Phil Hardberger asking for assistance in “speeding up the process” in setting up that public meeting. The Mayor’s office says they spoke with Kirby as recently as last Friday, when he asked them to “hold off” because the Union is in negotiations with CPS. “So we’re waiting on them to some extent,” said Communications Director Rebeca Chapa.

Negotiations between the union and CPS’s attorneys continue this week. One request made by CPS attorneys was that the IBEW work to have this article stopped, according to a union rep.

After hearing that, I made one more call to CPS’s public-relations department and left a voice-mail message. Then I called in on another line and was told that company spokesperson Theresa Cortez was on the other line and placed on hold. When the line picked up again I was told Cortez was “not available.”

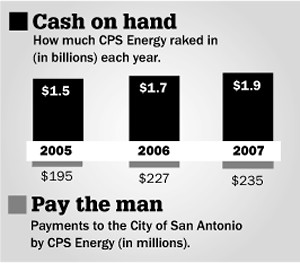

It’s important to remember we’re dependent on CPS for more than our lights. Increasing profits at CPS brought the city $235 million last year even as we enter deficit-budget territory for the first time in years `See “I O(wn) U,” Page 15`. The millions, however, are not a valid excuse for city leaders to continue turning a blind eye to goings-on within CPS. To the contrary, it’s greater cause to investigate, and deeply.

In the past year, there’s been a lot of noise about steering the utility toward greater investment in conservation and renewables. Some have suggested that the mission of the utility needs to be updated to reflect a deeper environmental commitment. Before anything like that can happen, the City must claim a greater degree of control over CPS. Until then, the pressure of providing San Antonio “low-cost power,” as their mandate requires, will drive management to push staff to limits at the expense of safety.

When the gears and sprockets — the meter readers, mappers, or linemen — are strained or abused, a meltdown can’t be far behind. •