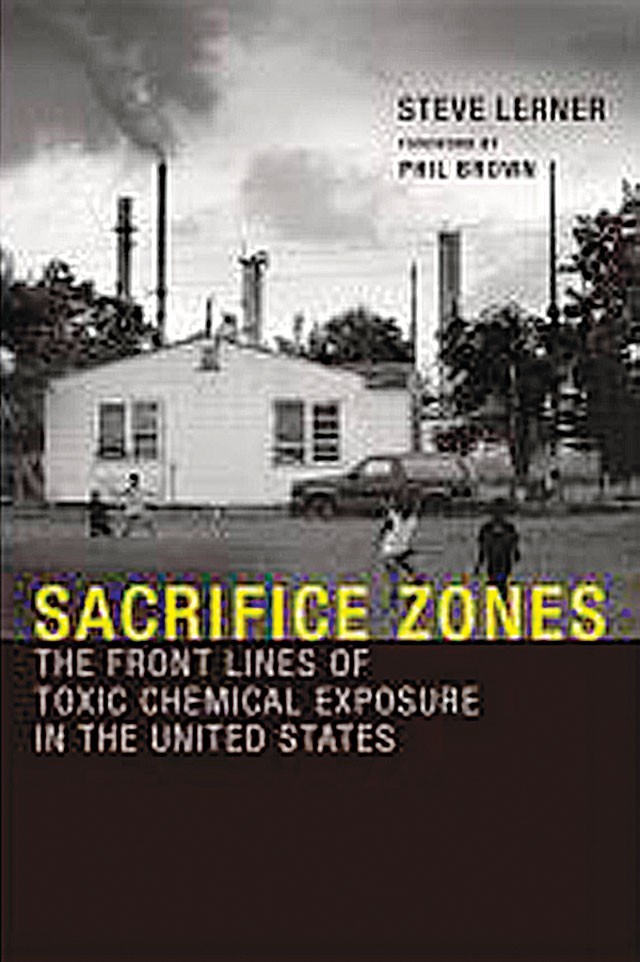

Grappling with how to own up to the toxic legacy of uranium mining and nuclear weapons processing in the United States, government officials coined the cold term “sacrifice zones” in the 1980s. In his recent book by the same name, environmental journalist Steve Lerner writes that the term today applies to a whole new swath of the American public, those “fenceline communities,” as he calls them, left to deal with the poisonous legacy of chemical contamination from military and industrial facilities in their backyards. History shows us that the chemical runoff and waste dumping of America’s heavy industry punishes minority communities and those at the bottom of the socio-economic ladder the hardest.

Sociologist Robert Bullard helped popularize the concept of “environmental racism,” the practice of clustering landfills, hazardous waste dumps, and heavy industrial polluters in poverty-stricken neighborhoods, often those of color, when in 1979 he helped spearhead a class-action discrimination lawsuit against a Houston-area solid waste company. African-American communities hosted six of the city’s eight solid waste landfills, even though African Americans only comprised 28 percent of the city’s population.

Further studies in the ‘80s and ‘90s painted a bleak picture: industrial polluters overwhelmingly opted to set up shop near poor neighborhoods — areas where residents don’t have the means to pack up and move when the air or water grows tainted. A much-cited 2005 Associated Press investigation revealed that blacks were 79 percent more likely than whites to live in neighborhoods with industrial pollution, while Hispanics were twice as likely as non-Hispanics to live in such “sacrifice zones.”

In Warren County, N.C., officials approved burying 32,000 cubic yards of soil contaminated with toxic polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in a predominantly black community. In Corpus Christi, oil waste dumps, later converted into general hazardous waste sites, bookend two formerly race-zoned neighborhoods (city officials in 1940 reserved one of the neighborhoods for “Mexicans,” the other for “Negroes”). Residents in one predominantly black neighborhood in Pensacola, Fla., lived for decades sandwiched between an Agrico Chemical Company fertilizer plant, later dubbed “Mount Dioxin,” and a sprawling wood treatment facility, forced to live in a chemical bubble riddled with cancer-causers dioxin, polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and arsenic. Plant workers and residents showed elevated levels of dioxin in their blood even 25 years after the facilities shuttered.

“Within these sacrifice zones, the human cost of our rough-and-tumble, winner-take-all economic system is brutally visible,” Lerner writes. “Here we can see the tragic consequences of discriminatory zoning practices, our inconsistent standards about health effects of toxic chemicals, and our gap-ridden regulatory system.”

If that weren’t bad enough, Lerner writes that even when industries are fined for polluting their neighbors those fines are influenced by the race of those polluted on. The average fine imposed on polluters impacting majority-white areas is a staggering 506 percent higher than the average fine imposed in minority communities, Lerner found in an examination of federal Superfund sites.

Sacrifice Zones: The Front Lines of Toxic Chemical Exposure in the United States

Steve Lerner

MIT Press

$29.95

368 pages