Easily among the more far-flung creative components of San Antonio’s Tricentennial celebration, “Common Currents” is an innovative exhibition series uniting 300 artists — each of whom was tasked with creating work inspired by a single year in our city’s complex history. Employing an unpredictable, artist-driven format, the sprawling project allowed six venues (Artpace, Blue Star Contemporary, Southwest School of Art, Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, Carver Community Cultural Center and the Mexican Cultural Institute) to each enlist two artists. That initial group of 12 followed suit, with each artist inviting two peers — and so on until a total of 300 were on board. Admittedly, this “chain letter-inspired” framework put artists in the driver’s seat to “make decisions that may traditionally be the role of the organization or curator.”

In an effort to build a San Antonio timeline informed exclusively by the words and images of artists, we reached out to an assortment of “Common Currents” participants to quiz them about what their concentrated research uncovered and how their findings translated into the visual realm.

How did you conduct your research and what did you discover about your specific year in San Antonio’s history?

Starting off, I did as much research as I could about how San Antonio came to be. The narrative about Fray Antonio de Olivares seemed pretty set, but there were so many questions that I still had about what was excluded from that story. I also heavily researched relics and reliquaries by reading books and talking to Dr. Annie M. Labatt, a professor at UTSA and expert in Byzantine Studies.

What specifically about your assigned year inspired your piece for “Common Currents”?

I kept being drawn back to St. Anthony, our namesake and patron saint of that which has been lost. But as I considered our history, my thinking shifted from that which has been lost to that which we could possibly find.

How did your piece take shape? What materials were used?

I wanted to incorporate the past, present and future into the reliquary I made and thought a lot about what happened before recorded history. That period is represented by a piece of limestone that I dug up at Yanaguana (San Pedro Springs), where people have gathered for thousands of years. The third-class relic of St. Anthony embedded in the limestone roots us in our current time through name and raises questions about the memory and faith required in birth narratives. The participatory component of the piece, that people can reach into the vitrine and touch the relic, will hopefully lead people out of the gallery into the community with an eagerness to discover.

How did you conduct your research and what did you discover about your specific year in San Antonio’s history?

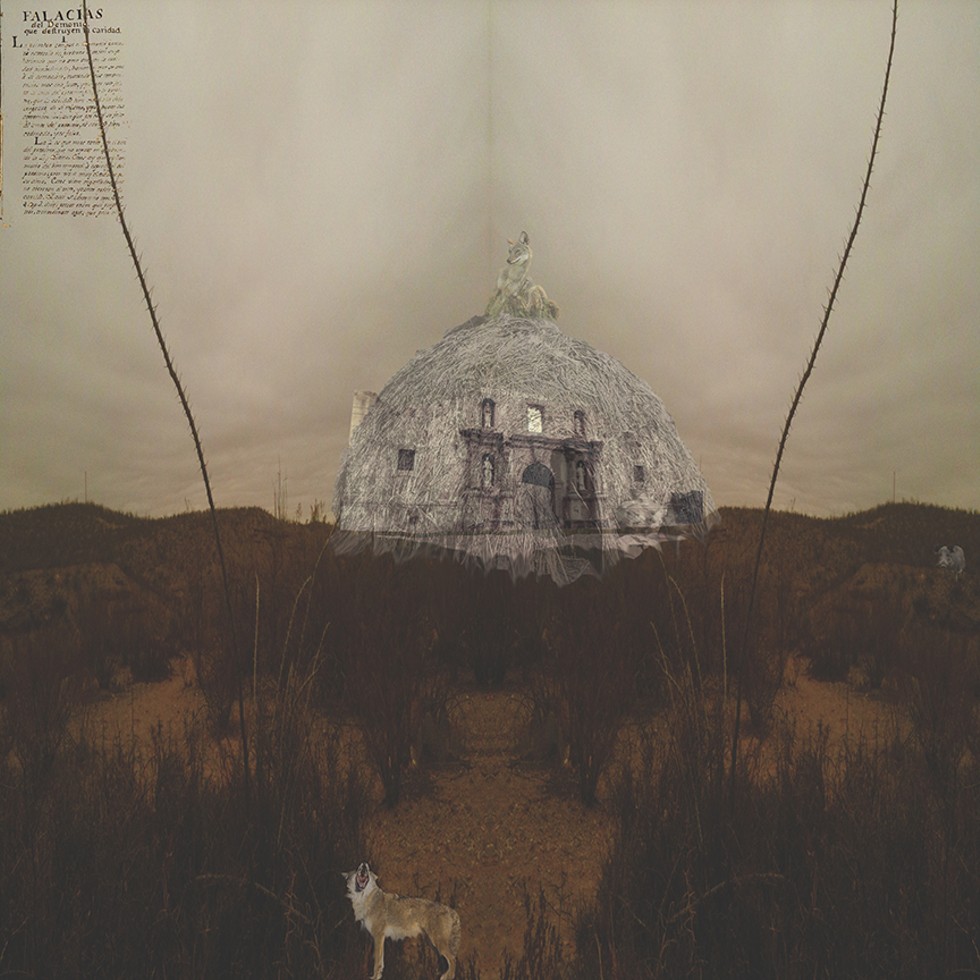

Online research. Here’s what I discovered: The Coahuiltecan were the nomadic, indigenous people living in San Antonio and surrounding areas in 1724. That year, a severe storm, possibly a hurricane, destroyed the original Alamo (Mission San Antonio de Valero) at San Pedro Springs, which was simply a series of huts that had been used by the Spanish missionaries to indoctrinate the Coahuiltecan into Christianity. That same year after the storm, construction began on the “new” Alamo at the location where it now sits, and where this process of indoctrination continued. This piece foregrounds the Coahuiltecan wickiup — the impermanent, portable dwellings they constructed out of brush and branches — in a black-and-white, somewhat removed image that is in the process of being airbrushed/disintegrated into the landscape. Behind the wickiup and bleeding through it is an image of the Alamo on its current site shortly after it was reduced to ruins. The layered structures sit high in a harsh landscape with gathering clouds — a coming storm. A page of text used in the missionaries’ enculturation/indoctrination process entitled “Fallacías del Demonio Que Destruyen la Caridad” hovers over and intrudes on the landscape. The Coahuiltecan hunted javelina and wore coyote skins, thus the appearance of these animals in the motif.

What specifically about your assigned year inspired your piece for “Common Currents”?

Current events and activism — specifically Standing Rock and all pipeline fights and environmental activism that is being led by indigenous people of the U.S. I wouldn’t say “inspired,” let’s instead say determined to talk about this long-standing injustice, through image, in a way that does not bludgeon the audience with didactics and/or strident and obvious opinion-mongering. In addition to that, the oppression by European white men of the Coahuiltecan and the indoctrination of them by the Spanish settlers who started the missions. I wanted to present an image that pays homage and respect to the Coahuiltecan and all indigenous people, as it is high time that reparations are made to them for all that the white man took and continues to take from them in our present day. The history of the U.S. is a particularly difficult one, built on the extermination of indigenous people and slavery, and maintained by the subjugation of women. Since the subject of the Tricentennial is 300 years of San Antonio’s history, it is an excellent time to comment on that history’s realities — and debunk some of the myths taught to our children in Texas history books.

One year, in the span of 300 years, is not a lot of time. I chose to take a broader view, the most obvious thread for me, as I conducted my research ... how the “old” and “new” worlds were coming together.

What specifically about your assigned year inspired your piece for “Common Currents”?

[The year] 1736 is very early on in the history of the city. What I found most interesting about the time period is how settlement of the area was rooted in introducing new cultures, languages and religions to the area.

How did your piece take shape? What materials were used?

The work is a digital collage of photographed images. I was drawn to the idea of how, at a particular point in time, one world enveloped another. Most of the images are drawn from a stock of photos I have taken and archived over the years.

How did you conduct your research and what did you discover about your specific year in San Antonio’s history?

I started my research by referring to the San Antonio Conservation Society, Texas State Library & Archives Commission, and the National Park Service website. What I found was that Mission Concepción was dedicated in 1755, and its structure appears very much as it did over two centuries ago. In its heyday, colorful geometric designs covered its surface, but the patterns have long since faded or been worn away. In 1757, work began on the construction of an enclosing stone defensive wall for the compound.

What specifically about your assigned year inspired your piece for “Common Currents”?

While I initially thought about creating a stone wall construction surrounding the mission, when I took a visit to the mission myself, I decided I wanted to pay tribute to the structure the stone wall would be protecting instead. Plus, in a way, the frame symbolizes the wall. I wanted to keep the piece as minimal as possible, but also be able to show a passage of time.

How did your piece take shape? What materials were used?

My medium is mainly mixed media — handmade paper, print, old photographs and embroidery. Since there were no photographs available in 1757, I had to create my piece entirely from handmade paper and assorted mixed media, including cardboard, thread and fabric. The pulp used was mixed with debris (dirt, etc.) found on the grounds of Mission Concepción. The fabric and embroidery application used was meant to reflect the beautiful and colorful facade the mission once had.

How did you conduct your research and what did you discover about your specific year in San Antonio’s history?

The Briscoe Center for American History has an online archive of scanned documents that was super helpful. I read through hundreds of them before learning about Rancho de las Cabras after talking with my good friend Scott Ball.

What specifically about your assigned year inspired your piece for “Common Currents”?

Everyone knows about the missions in San Antonio, but I felt like this ranching outpost for San Francisco de la Espada isn’t as well known. Rancho de las Cabras is in ruins, so I knew there wouldn’t be much to photograph out there. I brainstormed on how I could create something visual to get folks to stop by my piece and read about 1788. Rancho de las Cabras translated to English is “Ranch of the Goats.” So I made a portrait of Carla at Pure Luck Farm and Dairy in Dripping Springs.

How did your piece take shape? What materials were used?

I had photographed Pure Luck for a cheese magazine a couple years ago, so I made a call and they were kind enough to let me come out one afternoon to take these photos. I mostly chased goats around the property and would only get one or two frames in front of the backdrop before they would run off. Luckily, a dog barked while Carla was standing there and she raised her head and ears to listen — and I was able to make this photo in that moment. I’m not sure what the dog’s name was, but it was the real MVP.

How did you conduct your research and what did you discover about your specific year in San Antonio’s history?

This work emerged primarily from an archive of government documents that were generated among the bureaucracy in 1790 Nueva España territory, which I found in the Bexar Archives Online, provided by the Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin. It’s really a fantastic archive — you can search by year, and they have high-res scans of each original document, accompanied by text-only versions and translations. It was mostly letters between viceroy officials, and military and census reports, but they were beautiful hand-written objects, which reflect the time they were made ... In aggregate, these documents open a small window into what life was like in a 72-year-old San Antonio. What was most interesting to me was that the tone of the correspondence felt very contemporary. My expectations were that people had more time back in 1790, and this would come across in how they crafted their correspondence, but the opposite was true. Their letters read as urgent and squeezed-out — just as full of brief and temporary feelings as a text or an email. It occurred to me that the distance between people must have been behind that, and weighed heavily on their minds. They wanted to get their response down and back in the hands of a mail carrier as soon as possible. The scale of that was interesting to me.

What specifically about your assigned year inspired your piece for “Common Currents”?

I was interested in the contrast between their apparent sense of time, and the vastness of the distance in the territory. They seemed so preoccupied with the day-to-day, it made me wonder what they were missing. So I tried to find reference to events outside of this human/social scale, like weather and astronomy. I got lucky and found out there was a comet visible that year, which produced a meteor shower — as well as a 1790 published reference to an aurora seen as far south as Mexico City the previous year.

How did your piece take shape? What materials were used?

I couldn’t pass up the aurora — it fit nicely into some of the painting processes I’m working with now. I used those same methods to build an abstraction of the aurora, comet and meteor shower that may have been visible from what was San Antonio at that point. Then I titled the piece with a quote from one of the letters I had found. It was an admonition from an army officer to his subordinate, who had moved some horses to the coast without permission.

How did you conduct your research and what did you discover about your specific year in San Antonio’s history?

I spoke to a history teacher, referenced some history books and historical blogs. The actions of Juan Bautista de las Casas and the Casas Revolt were pivotal to Mexican independence.

What specifically about your assigned year inspired your piece for “Common Currents”?

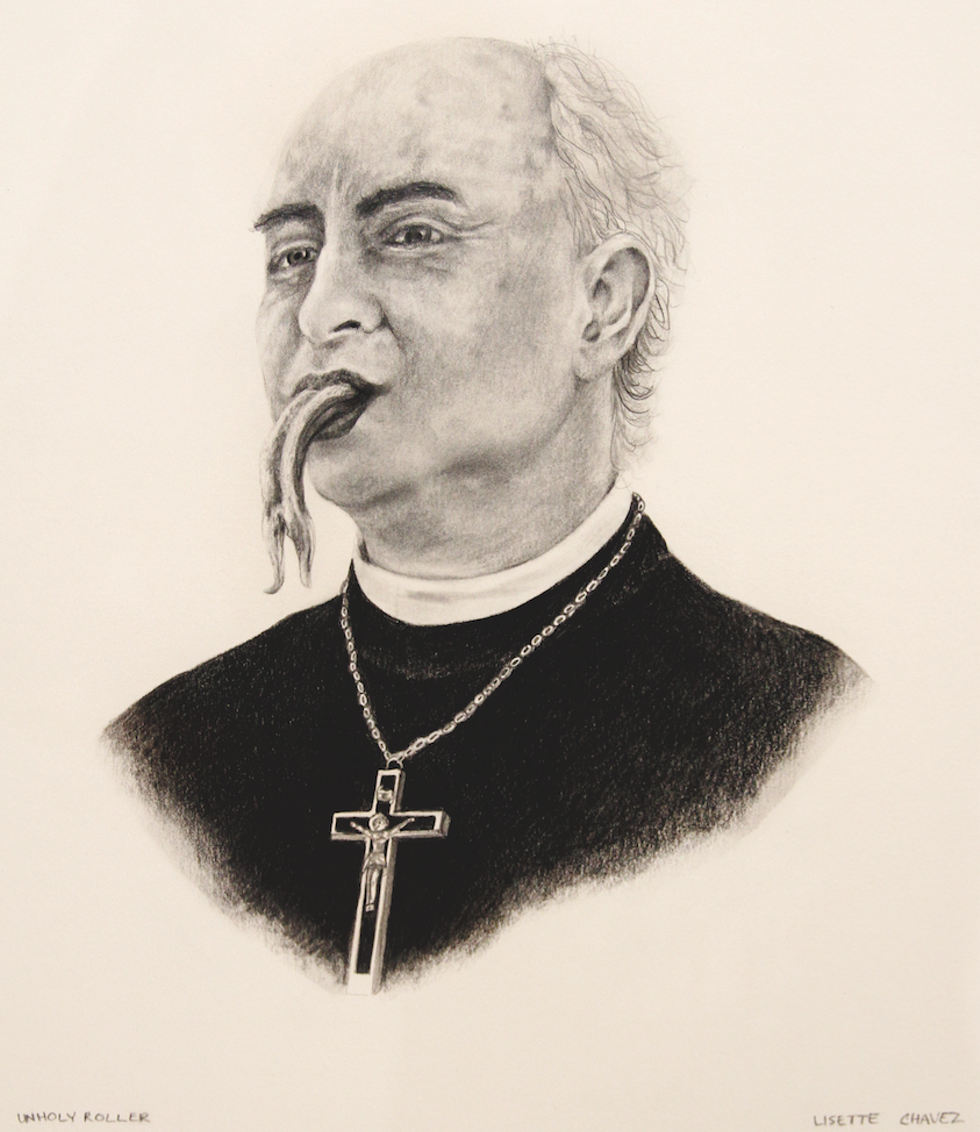

Within the past couple of years, my work has revealed my frustration with religious hypocrisy. In my research, I learned about a subdeacon whose violent behaviors and debaucheries often created tensions with government officials. I’m always captivated by people who use religion as a front to cover up their wrongdoings.

How did your piece take shape? What materials were used?

A really interesting detail about this piece is that I was reading about someone and was not able to find any images of their likeness. I had to ask myself what someone with these traits might look like. I created a graphite and charcoal drawing of a holy man with a forked-tongue — someone who says one thing but does another.

What specifically about your assigned year inspired your piece for “Common Currents”?

I found out that the first Chinaberry trees were introduced to San Antonio around my year, which sparked inspiration because my work deals with trees, environmental issues and material culture. Then I researched further into how the city has been interacting with these trees since their arrival.

How did your piece take shape? What materials were used?

I knew I wanted to incorporate handmade paper when referencing trees. That was an important material choice as well as using printmaking to emphasize the idea of multiples and the invasiveness of the species. It went through several revisions before I decided on the right form and structure. It also evolved conceptually. I started relating to the trees as people. I thought about how many of our ancestors arrived in San Antonio from somewhere else and what the overall attitudes towards non-natives were.

How did you conduct your research and what did you discover about your specific year in San Antonio’s history?

Well first, I’d like to say that most of the artists involved did a very thorough job of researching their assigned year, after which they created an engaging and informative work of art that represents San Antonio’s history. On the other hand, I just found an image that was taken somewhere around the 1860s, and then I created a work of fiction.

What specifically about your assigned year inspired your piece for “Common Currents”?

What inspired me, if that’s the right term, was the dichotomy between the historic significance of the Alamo as a monument that helped shape the story of Texas, and the current commercialization of the surrounding area.

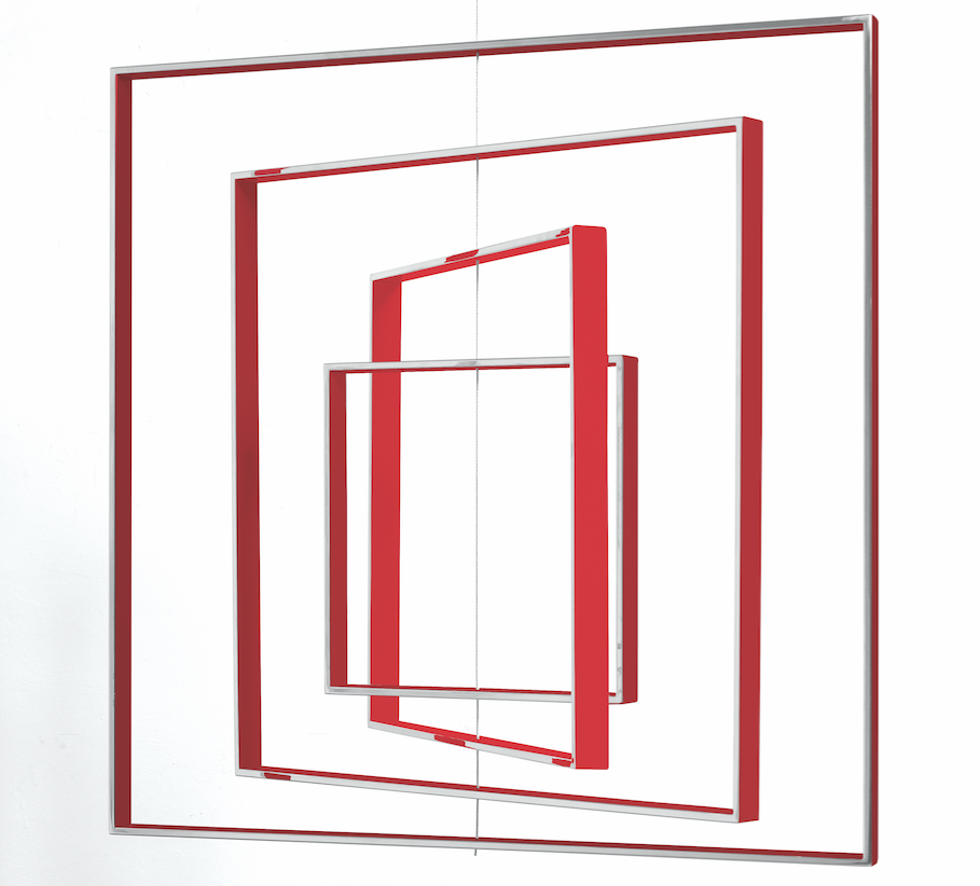

Artist: Jose Dávila | Invited by: Mexican Cultural Institute | Year: 1968

What can you tell me about the year you were assigned?

I was assigned 1968 — a key date in world history, a turning point even. It was also the year in which the World’s Fair was held in San Antonio with a theme of “The Confluence of Civilizations in the Americas.”

What specifically about your assigned year inspired your piece for “Common Currents”?

The mobile [I created] is a spatial take on the geometric structure of the famous “Homage to the Square” paintings and prints by Joseph Albers — it even holds its same proportion. In 1954, Albers mentioned that his squares “moved” in and out, and grew and diminished according to our perception of color and their interaction.

How did your piece take shape? What materials were used?

Josef and Anni Albers traveled constantly to Mexico and other countries in Latin America, constructing a strong connection and understanding between cultures which, at the same time, permeate into their work. I chose a particular set of red tones for the mobile that comes from an “Homage to the Square” Albers painted in 1968. The red tones resemble the color pigments found in Mitla, an archaeological site in Mexico, which in turn inspired Albers in his geometric graphic work. The forms that come from the Mesoamerican tradition encounter Modernist Geometric Abstraction through the eyes of a visiting ex-Bauhaus professor. A confluence of civilizations on its own.

What can you tell me about the year you were assigned?

I was assigned 1968 — a key date in world history, a turning point even. It was also the year in which the World’s Fair was held in San Antonio with a theme of “The Confluence of Civilizations in the Americas.”

What specifically about your assigned year inspired your piece for “Common Currents”?

The mobile [I created] is a spatial take on the geometric structure of the famous “Homage to the Square” paintings and prints by Joseph Albers — it even holds its same proportion. In 1954, Albers mentioned that his squares “moved” in and out, and grew and diminished according to our perception of color and their interaction.

How did your piece take shape? What materials were used?

Josef and Anni Albers traveled constantly to Mexico and other countries in Latin America, constructing a strong connection and understanding between cultures which, at the same time, permeate into their work. I chose a particular set of red tones for the mobile that comes from an “Homage to the Square” Albers painted in 1968. The red tones resemble the color pigments found in Mitla, an archaeological site in Mexico, which in turn inspired Albers in his geometric graphic work. The forms that come from the Mesoamerican tradition encounter Modernist Geometric Abstraction through the eyes of a visiting ex-Bauhaus professor. A confluence of civilizations on its own.

How did you conduct your research and what did you discover about your specific year in San Antonio’s history?

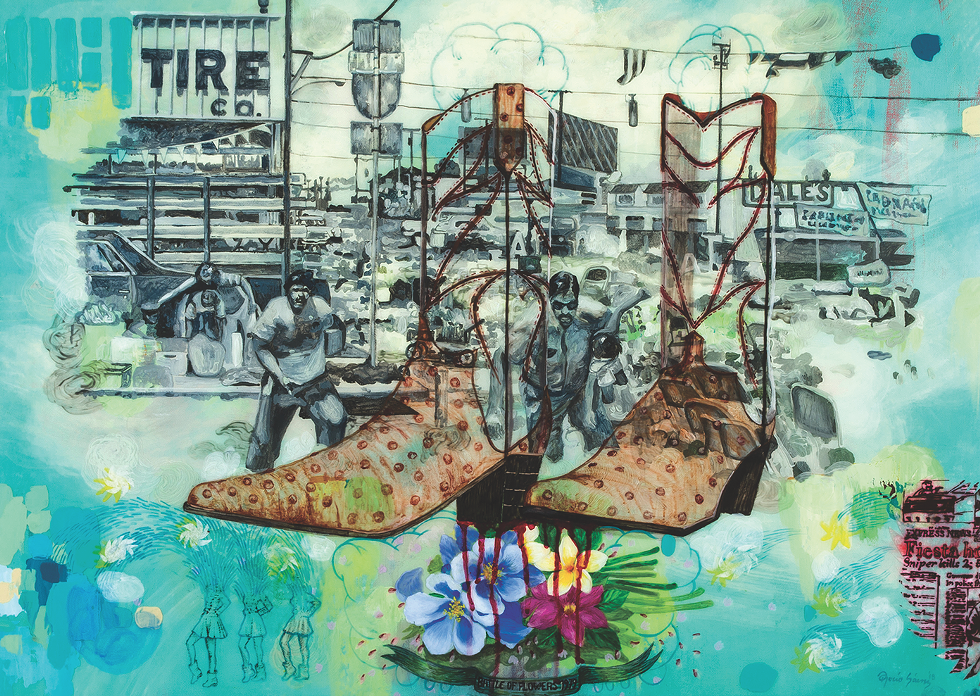

The first thing I did was investigate the news most relevant to this year on the internet. I found various events — from a KISS concert to crimes, accidents and photographs of that year’s prize-winning cow. But above all, what caught my attention happened to be the Battle of Flowers Parade and the development of the giant boots at North Star Mall.

What specifically about your assigned year inspired your piece for “Common Currents”?

The piece is [based on] two exceptional events that happened in San Antonio in 1979: the shooting during the Battle of Flowers Parade and the inauguration of the giant cowboy boots erected in front of North Star Mall. The Battle of Flowers is a celebration that has commemorated, each year since 1891, the Battle of the Alamo’s fallen Americans and celebrates the United States’ triumph over Mexican troops in the Battle of San Jacinto and the reclamation of Mexican territory. In 1979, a battle was literally fought, in which a sniper attacked spectators with bullets. The boots not only represent part of the identity and habits of Texans, but also function within the painting as a symbol of the belief that America has been chosen by God for a special destiny ... large and powerful. Behind the boots are overlaid images depicting some of the chaos and terror that occurred that April. These events can be taken at first glance as two parallel stories, but that’s not the case: They are woven together in the same network, in the same year. They share an origin within a complex political and social phenomenon.