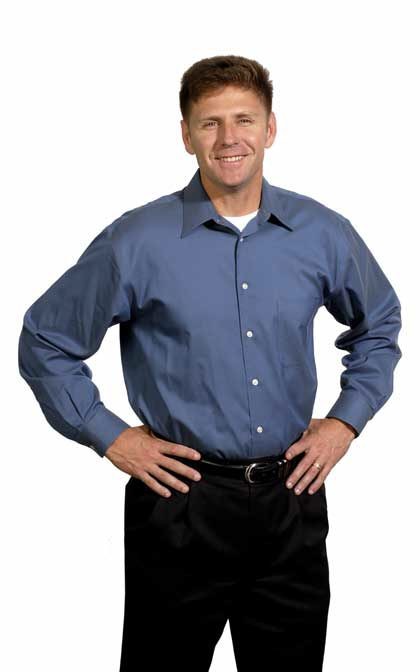

At a time when Democratic muscle in this state is at a low ebb, Garcia is more than a mere candidate for a Coastal Bend district seat. He’s a symbol of his party’s attempt to take back the state, one race at a time. If you approached central casting for the perfect political candidate, you’d end up with someone much like Juan Garcia. He’s young (40), handsome, a graduate of Harvard Law School, a Naval aviator who flew several missions over the Persian Gulf, a dedicated family man, and a relentlessly affable and engaging character. If he possesses a dark side, it’ll probably reveal itself about the same time WMDs turn up in Iraq.

Like Cisneros, he’s a Latino with crossover appeal, and like Bill Clinton, he defies traditional notions of what it means to be a Democrat, earning the highest possible rating from the state’s rifle association and talking tough on the hot-button issue of immigration. Unlike Cisneros and Clinton, however, he doesn’t appear to be carrying any self-destructive personal baggage.

Standing before a crowd of more than 100 avid supporters outside Taft Farm Supply, a red-and-white corrugated warehouse in the middle of town, Garcia falls back on the self-effacing humor that comes naturally to him. Introducing Cisneros to the crowd, he says, “What a special day it is to be with you, and one of our heroes, on a day when we think our youngest child might be potty-trained.”

When Garcia poses inside with a group of Taft honor students, he cracks: “This is the closest I’ve ever been to the National Honor Society.” The line gets a laugh, but no one really buys it. Garcia is a classic, first-child overachiever, someone who, by his own admission, has spent most of his life preparing for a career in politics.

Along the way, he’s built a résumé so formidable that it very nearly overshadows the candidate himself. It’s the first topic that comes to mind when you approach Garcia supporters for anecdotes about the man. Even Garcia’s baby brother Mike, a 23-year-old flight trainee at the Naval Air Station Corpus Christi, can’t help but rave about it.

“He’s got a résumé that’s very impressive, and you wouldn’t know any different from any interaction with him,” Mike says. “He’s very humble. He’s the real deal, and I think he has sincere intentions to help people.”

Watching Garcia stand next to Cisneros, in nearly identical pale-blue shirts, red ties (although Cisneros’s tie has a maroon, Texas A&M tint), and black slacks, you’re struck by their similarities: tall, wiry, radiating can-do optimism, and able to make whoever they’re speaking to feel like the center of the universe.

As Cisneros himself points out, there are many “interconnections” between them: Both are South Texas Democrats, both attended Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, and both served as White House Fellows. Both also chose to return to their South Texas roots after completing their education rather than pursue lucrative options elsewhere.

“`Garcia` is Henry Cisneros,” says Christian Archer, manager of Phil Hardberger’s successful 2005 mayoral campaign, and a member of Garcia’s campaign team. “When Henry walks into a room, all the oxygen leaves the room and everyone is focused on him. Juan is like that.”

Garcia likes to say that “you only have one chance to be a first-time candidate” and he chose this race with the sense of deliberation he’s brought to every aspect of his career. Rather than searching for a sure, easy win, he decided to challenge Seaman, a Republican completing his fifth term in the legislature, in a district that’s generally been an electoral lock for the GOP.

In every contentious political campaign, there is an 800-pound gorilla hiding in the war room, an overriding issue that everyone thinks about but few people feel comfortable discussing. In the 1960 presidential race, it was John Kennedy’s Catholicism. In 1968, it was Richard Nixon’s temperament. In 1984, it was Ronald Reagan’s age, and in 2000, it was George W. Bush’s intelligence.

In the 2006 District 32 race, that issue is whether a Latino can break through with an overwhelmingly Anglo electorate. Archer and other Garcia confidantes speak about it as an imposing mountain to climb, all the more reason they believe a Garcia victory would automatically elevate him to major-player status in state politics. But that theory neglects the other 800-pound gorilla in the room, which is the fact that Garcia — with his blue eyes, sandy brown hair, and light complexion — looks at least as Anglo as Seaman.

For his part, Seaman, 76, knows he’s in a serious tussle. Early this year, he wrote a letter to his supporters, informing them that he is “engaged in a major fight” for his political life, and urging them to “consider doubling or tripling” their standard donations. The Texas Progressive Alliance has focused on Garcia as part of a three-candidate slate (along with Congressional candidate Shane Sklar and Agriculture Commissioner hopeful Hank Gilbert) they’re backing with an online fundraising campaign. And according to campaign-finance reports submitted by the two candidates, during the first half of this year, Garcia raised more than twice as much money as Seaman: $205,956 to $89,956.

The Corpus Christi Police Officers Association endorsed Seaman in 2004, but Domingo Ibarra, the organization’s president, sounds disillusioned with the state rep’s job performance.

“It’s concerning to me that I’ve never had access or contact with Mr. Seaman until now, that he’s running for office,” says Ibarra, who’s been an association member since 1989, and its president since January of this year. “Now that he’s on the campaign trail, Mr. Seaman came over to our office and finally met with our board of directors.”

Ibarra has yet to officially endorse Garcia, but he’s clearly leaning in that direction. “`Garcia` is well-spoken, but he’s also exceptionally intelligent,” he says. “He has a deeper understanding and an immediate grasp of the issues at hand. Even the incumbent

doesn’t have the level of understanding that Mr. Garcia has. Maybe that’s because of the concentrated attention he devotes to the issues as opposed to what his opponent has demonstrated to us.”

Seaman also faces questions about an Austin condominium for which he has paid $1,000 a month in rent for at least four years, according to campaign-expenditure reports filed with the Texas Ethics Commission. Seaman identifies the recipient of these payments as Austin Land Company, but Seaman spokesman Mac McCall recently told the Corpus Christi Caller that the condo is actually owned by Ellen Seaman, the representative’s wife. State law prohibits a political candidate from personally benefiting from campaign contributions, but McCall has argued that the representative did not benefit from his wife’s real-estate interests.

Seaman has also claimed a homestead exemption for the condo as well as his Corpus Christi home, an apparent violation of state law, which prohibits the claiming of multiple properties for homstead exemptions.

Even with such obstacles in his path, Seaman will be a tough opponent to unseat, and Garcia campaign workers know it. According to their own estimates, they knocked on 55,000 doors by the end of August, and they plan to make three or four return trips to each home by November.

Garcia tightly honed his message before launching his campaign, and that message is so tightly honed that he occasionally slips into rehearsed, soundbite language. More than once during an interview with the Current, he will defend a position by saying, with exactly the same inflections: “That’s not a Republican issue or a Democratic issue, that’s a Texas issue. Without being overdramatic, that’s an American issue.”

He clearly embraces his role as a so-called “New Democrat,” and seems to be tapping into a partisanship fatigue that’s affecting even this most partisan

| “I felt if ever down the road, I was somehow involved in that most sensitive, sacred of decisions — whether to send young men and women into harm’s way — I wanted to have taken a turn myself.” — Juan Garcia |

“I had a different experience growing up,” Garcia explains. “I’m from South Texas and my family’s from a poor town, but I grew up around Navy bases around the country. One thing I’ve definitively learned in this great civics lesson of an experience over the last eight months is that people are ready to transcend party.”

If you’re looking for a turning point in the see-saw battle between Texas Democrats and Republicans, you’d be well advised to go back to May 8, 1976.

That was the day Ronald Reagan trounced incumbent Gerald Ford in the state’s presidential primary. The primary electrified not only the Reagan campaign — which lagged far behind Ford in delegates up to that point — but the then-inept Texas GOP.

A May 10, 1976, Time magazine primary recap noted that Texas Republicans were “organized haphazardly, if at all,” and pointed out that Republicans couldn’t even vote in 44 of the state’s 254 counties, because no polling booths were available for them.

Two years after Reagan’s right-wing warning shot, Bill Clements was the first Republican elected governor of Texas since Reconstruction. Two years after that, Reagan won an easy presidential victory, and many of the Texas Democrats who’d temporarily defected to his side in 1976 began to seek permanent refuge within the Republican ranks. Over the next two decades, Republicans gained control of Texas politics at every level, culminating with the 2004 campaign, in which the GOP won more than 80 percent of Texas elections that included a Republican on the ballot.

District 32 has proven to be even more staunchly Republican than the rest of the state, with Republicans carrying the district in 2004 in seven of eight contested elections and consistently putting up better numbers in the district than around the state. For example, Democratic U.S. Representative Solomon Ortiz carried the 2004 election with more than 64 percent of the vote, but received less than 44 percent of the vote in District 32.

Garcia recognizes the challenge inherent in this race, and carefully considered it before announcing his bid for Seaman’s seat. “I wanted to be smart about it,” he says. “We weighed other scenarios, were approached about other scenarios. But I think there’s a unique opportunity here.

“I came back home to raise my kids to a South Texas that’s second from the bottom in SAT scores, dead last in high-school dropout rate, pays our teachers well below the national mean despite paying some of the highest property taxes in the country. I think there’s a chance for even a freshman for what may be the out-of-power party to have an immediate impact in a hurry.”

Garcia was the first of five brothers born to Juan and Patricia Garcia. His father was a Naval aviator and Garcia says the family relocated 19 times in his parents’ first 20 years of marriage.

If Garcia exudes a Kennedy-esque sense of glamour, he also shares that family’s penchant for referring to elective office as “public service” — to view it as a high-minded contribution you make to your country. Garcia says he knew from early childhood that he wanted that kind of career, and he’s never veered from that path.

At Harvard Law School, he completed a joint four-year program emphasizing government and public service, enabling him to leave with a law degree as well as a Master’s from the Kennedy School of Government.

His wife, Denise Giraldez Garcia, also attended Harvard Law School during the same period, and he says he chased the Brooklyn, New York, native “relentlessly for three years with zero success.” Years later, while she was practicing law in Washington, D.C., Garcia visited the nation’s capital on a Pentagon assignment, and made a point of tracking her down. “She was always the one that got away,” he recalls. “Four kids later, she’s still hanging around.”

He admiringly points out that his travels with the Navy have required her to pass five state-bar exams, and she has settled into a law career in Corpus Christi, specializing in estate planning, probate, and elder law.

Garcia’s decision to enlist in the Navy after completing his legal studies owed much to his father’s example, but it also sprang from an awareness that military experience could bolster his credibility for a future political run.

“I felt like if ever down the road, I was somehow involved in that most sensitive, sacred of decisions — whether to send young men and women into harm’s way — I wanted to have taken a turn myself,” Garcia says. When he first learned of the 9/11 attacks, while en route to the United States after a six-month tour in the Persian Gulf, one of his first thoughts was that it “would be valuable for this country to have policymakers who’d spent time in that part of the world.”

While others are awed by Garcia’s credentials, Donnie Sue Riojas is more impressed by the way he shrugs off his weighty resumé. Riojas, director of the Taft Housing Authority, says that when a stranger approached Garcia and asked if he’d attended college, he simply said, “Yes, up north.”

Riojas says: “He didn’t actually say where exactly, and to me that sends a humble message. That’s somebody that’s real, and that’s what we need.”

The Coastal Bend region faces a tough balancing act, because it sorely needs economic development, but one of its most reliable sources of jobs, the petrochemical industry, raises red flags with environmentalists.

Garcia compares the Coastal Bend to San Diego in the early 1950s, and says the key is growing the economy in a manner that doesn’t destroy what’s appealing about the area. On the issue of education, he insists that teacher pay scales must be raised above the national average, and he bemoans the glut of standardized testing affecting the public-school system.

“First, you’ve got to have the pre-test rally and then the post-test debriefing with the teachers, and then you go through the briefing with the students,” he says. “When does a teacher get to teach? When do we turn them loose to do what they do best?”

The issue that stirs the most passion in Garcia, however, is accountability. He notes that the Texas statehouse is one of only eight in the country that does not require lawmakers to openly document their vote. “Process that for a minute. That’s stunning,” Garcia says. “The system can’t work if you can’t hold your members accountable. That’s just Civics 101. We teach our kids about taxation without representation. I call this representation without representation.”

Seaman has emphasized the experience issue, warning District 32 voters that they’re seeing a “seniority drain” in legislative representation. He’s also taken the controversial step of belittling Garcia’s 13 years of active duty in the military, saying, “He’s not a fighter pilot. He never flew jets, he flew P-3s `patrol planes`.” Bloggers have denounced this statement as an attempt to “swift boat” Garcia, a reference to 2004 attacks on Democratic presidential nominee John Kerry’s Vietnam War record.

Garcia paints Seaman as an out-of-touch pawn of big insurance, pointing out that Seaman has taken almost a half-million dollars from insurance companies in the last 10 years. Rather than directly addressing Seaman’s attacks on his Naval career, he calmly argues that every contribution is worthy of respect.

“Anyone who’s served knows unequivocally that whether it’s the pilot or the admiral or the young 19-year-old cook in the bottom of the carrier, every link is inextricable,” he says. “To question anyone’s service who signed up for this volunteer force and kissed their family goodbye does a disservice to them and their family.”

As Garcia stands side by side with Henry Cisneros outside Taft Farm Supply, the pettier aspects of this campaign seem far away. Idealistic Garcia supporters model their “Army of Juan” T-shirts, campaign posters and balloons are everywhere, and the smell of barbecue fills the air.

In an interview with the Current, Cisneros describes Garcia as “one of the more promising talents I have seen anywhere in Texas, and even the United States. He’s in that classic tradition of people who have served the country in the military, and who have the personal attributes, temperament, to be in elective office. Obviously intelligent, dedicated to his family, and perhaps most interestingly, he could live anywhere in the United States, and he’s chosen to live in Corpus Christi.”

Cisneros is the event’s invited guest, and Garcia enthusiastically defers the spotlight to his role model, the former great Latino hope of Texas politics.

Cisneros swiftly reminds everyone what made him an ascendant star in the 1980s, as he begins a riff on the meaning of this election. It’s about your child’s education, your grandparent’s health care, the quality of the air you breathe, Cisneros insists. Again and again, he returns to the same point: “It’s not just politics. It’s personal!”

Garcia grins, undoubtedly mindful that his considerable political ambitions hinge on how well he makes his personal case over the next two months.