Jessica Azua moved from Mexico to the United States at 14 to join her father, who works as a carpenter in San Antonio.

She left her mother, brother and life back in Tampico with hope for a better education north of the border. At Brackenridge High, she built made friends with other undocumented peers from Mexico, joined the school's mariachi band and learned to play the violin.

Still, as she got older and began thinking about her future career, she soon learned that without a work permit or Social Security card, she wouldn't have much in the way of job options. And since she lacked legal status, Azua also couldn't get a driver's license and lived in fear of being deported if she got pulled over.

After earning her associate's degree in business at San Antonio College, she worked as a waitress at a local bar and bakery.

"I had a degree but I wasn't going to be able to do what I wanted to do," Azua recalls.

But then, a twist of fate seemed to offer a change in direction.

In 2012, the Obama administration created the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA, which allows undocumented youngsters who came to the U.S. as children, like Azua, to apply for employment authorization without fear of being deported. Azua, who had already been in San Antonio for six years when DACA was created, eagerly applied and was approved for the program, which provided a reprieve for two years.

She has since completed her bachelor's degree in business management from Texas A&M University and has a human resources job at the San Antonio office of the Texas Organizing Project, a statewide organization that advocates for social and economic equality for low-income Texans. Azua says she feels safe to drive now that she has an official driver's license, and she reapplied to the program last month. Her DACA status is set to expire in 2017.

"DACA has opened a lot of doors for me," she says, noting she'd like to eventually earn a master's degree. Now, she says, she can apply for more scholarships and travel without fear of being deported. "I know I can work, I know I can go to school and do what I want to do without being afraid."

In November of last year, Obama expanded DACA for three years and announced a similar program for undocumented parents of U.S. citizens, called Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA).

According to the Migration Policy Institute, a national nonpartisan think tank, about 3.7 million undocumented immigrants across the country would qualify for DAPA, which proponents say will enable hardworking individuals to come out of the shadows and contribute to the workforce without fear of deportation.

Opponents, including Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, have called Obama's order "illegal amnesty," arguing that the president is outside his authority to issue such an order. Texas is leading the charge against the move, the first of 27 states suing the administration over it.

The numbers, though, seem to counter critics' argument that Obama's executive action is equivalent to amnesty.

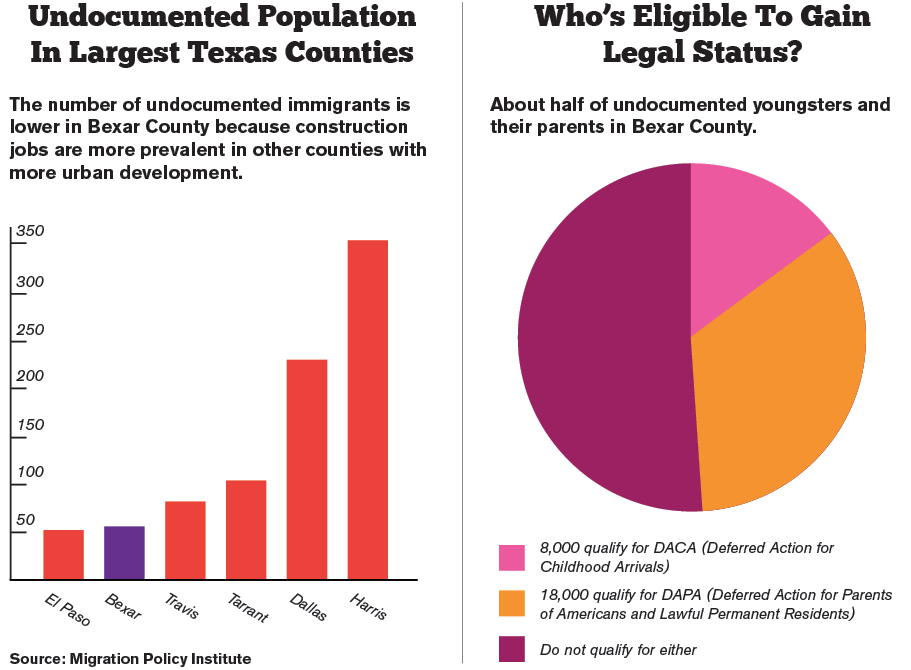

According to MPI, 8,000 immigrants in Bexar County qualify for DACA while 18,000 qualify for DAPA. That's half of the county's estimated undocumented population of 52,000.

David Spener, sociology and anthropology professor at Trinity University who specializes in U.S.-Mexico border studies, said that based on those numbers, it's hard to square the idea that the deferred action programs offer blanket amnesty to undocumented immigrants.

"You've got basically a little less than half in Bexar County who might be eligible for deferred relief of deportation, about half of the undocumented in San Antonio are out of luck," Spener says. "It's not a blanket, across the board amnesty by a long shot."