Recently, while reporting on the East Side’s Friedrich Lofts and the West Side’s Tampico Apartments, two high-profile developments in the downtown area, the rents the developers were forecasting seemed exorbitant, especially for units deemed “affordable.” So I dug a little.

To understand how rents are calculated we must start by identifying the two types of apartments: market-rate and subsidized rents.

With market-rate housing, the monthly rent is unrestricted. Developers dictate prices using the basic law of supply and demand. That’s why rents in and around the Pearl typically hover above $2 per square foot [visit the property websites, do the math and see for yourself] making it one of the most affluent submarkets in San Antonio, if not the most affluent.

Many properties use software-based systems to determine rents “on a daily or near-daily basis, similar to how airline ticket pricing is determined,” a city official told me in 2018.

But what about apartments priced below market-rate? Those that are supposed to be reserved as “affordable housing”? Those that are backed by government subsidies?

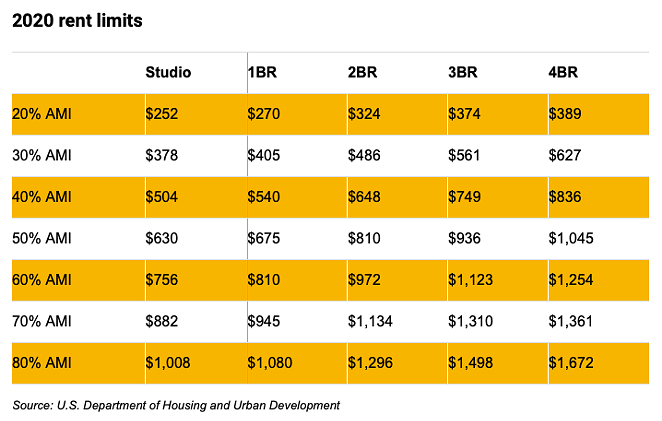

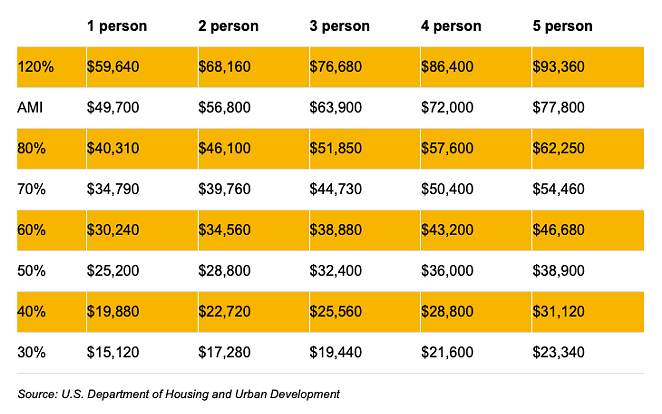

How Rent Limits WorkEvery year, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) issues rent limits for metro areas across the country. Most housing developments that receive federal funding or that participate in federal programs cannot charge more than the caps HUD sets. The rent levels are measured by how much a household makes if their wage or salary sits below the area median income, or AMI, which is $72,000 for a family of four in the San Antonio-New Braunfels region. Here’s what those caps look like locally:

A family earning 50% AMI, or less, cannot be charged more than $810 for a two-bedroom, for example.

HUD uses rent limits for programs such as housing choice vouchers, Community Development Block Grants, the HOME Investment Partnerships Program, and low-income housing tax credits, among others.

Many, if not most, affordable housing tools at the local level also adhere to HUD’s rent limits, even if no federal money or subsidy is infused into the project. That’s because HUD is the standard for all things housing in the U.S.

For example, local programs such as the city’s Center City Housing Incentive Policy and the fee waiver program abide by HUD’s rent limits. The San Antonio Housing Authority (SAHA) observes HUD’s benchmarks for obvious reasons, SAHA being the local arm of HUD.

There are, however, exceptions.

The San Antonio Housing Trust, a nonprofit entity formed by the City of San Antonio, is one of the largest partners of “affordable housing” developments in San Antonio and usually adheres to HUD’s rent limits. Usually.

Here’s a great example where it doesn’t.

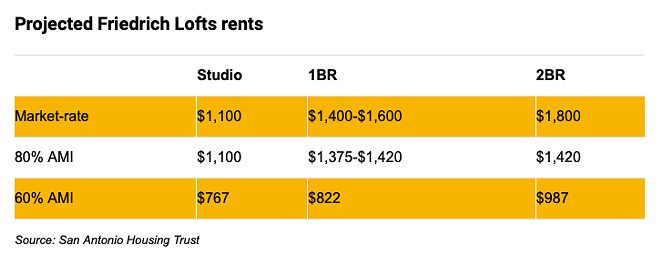

The Friedrich Lofts is the envisioned 347-unit redevelopment of the old Friedrich Air Conditioning complex on East Commerce Street. The $68.7 million project is a partnership between the housing trust, Dallas developer Provident Realty Advisors, and Atlanta-based investor American South Real Estate Fund. The housing trust’s involvement, through an entity called a public facility corporation, means the partnership benefits from property tax exemption status under state law. All of the deals struck between the trust and a developer are approved by the trust’s board, which is composed of five City Council members.

Of the 347 units, 173 will be market-rate priced, 160 apartments priced for people making up to 80% AMI, and 13 for households making up to 60% AMI.

Which is all fine and dandy, but let’s look at actual rents:

Now compare these 80% and 60% AMI or less rent prices to HUD’s rent limits shown in the first table.

You’ll find the prices for a 60% AMI studio apartment, for example, are very close: $767 at the Friedrich compared to HUD’s cap of $756. Same for a 60% AMI one-bedroom: $822 at the Friedrich versus HUD’s limit of $810. Friedrich’s numbers are slightly higher because they are predictions of what HUD’s rent limits will be two years from now, which is roughly the amount of time it takes for a development to be built.

The 80% AMI rents at the Friedrich are a different story.

According to Pete Alanis, the housing trust’s interim executive director, the 80% AMI rents at Friedrich do not adhere to HUD’s rent limits. He said the only way the lender, American South Real Estate Fund, would commit to the deal is if the 80% AMI rents were priced at a certain level, which are higher than HUD’s rent limits. Some context: This latest iteration of the Friedrich, which has seen multiple redevelopment attempts fail over the years, was delayed because the development group [the housing trust and Provident of Dallas] couldn’t find an investor to commit to the Friedrich.

In June, Alanis said the development partnership agreed to give the investor, American South Real Estate Fund, a higher-than-normal ownership stake, 67%, in order to secure the equity the fund was bringing to the table.

“It’s the deal that is going to finally allow this project to proceed, and we’re finally going to have the Friedrich done,” Alanis said. “Otherwise, it just wouldn’t have happened.”

In a recent interview with the Heron, Alanis said he doesn’t want below market-rate rents of future trust partnerships that don’t align with HUD’s limits to become the trust’s modus operandi.

The trust, through its public facility corporation, has contributed a property tax exemption to more than 30 developments it has partnered with across the city—most of which are complete or under construction.

“Moving forward, my goal is to get all of the affordable rents within the … HUD-calculated max rent for bedroom size and household size,” Alanis said.

It’s worth nothing that the cost to build apartments doesn’t change. Businesses that provide labor, materials, and other goods and services don’t give developers a discount for the sake of producing more affordable housing in San Antonio. Government subsidies or incentives, such as the money saved from not having to pay property taxes, offset the development cost, therefore allowing the developer to drive down market-rate rents to below market-rate, and into the realm of affordable housing, in some cases.

Let’s pause for a second. How are you holding up? How about them Spurs, huh? Man they gave it their best shot in The Bubble, didn’t they? OK, we’re almost to the end. Finally: area median income, or AMI.

About AMIYes, but how are HUD rent limits determined?

It’s important to understand that in San Antonio below market-rate apartments don’t necessarily denote affordable housing. Go back to the rent limits chart: Do the 80% AMI rents seem affordable for San Antonio? For an efficiency, $1,008? For a one-bedroom, $1,080? Some developers would argue those rents are affordable compared to fast-gentrifying cities. They pair this argument with another: What San Antonio needs is higher wages, and the educational attainment and workforce development that goes along with them.

But, again, San Antonio is not other cities.

To be fair, some developers agree those rents shouldn’t be considered affordable in this city. In recent interviews with the Heron, Victor Miramontes, managing partner of Mission DG, which is building the Tampico Apartments with the help of the San Antonio Housing Authority’s tax exemption, and Mitch Meyer, who wanted to build apartments next to the Hays Street Bridge, both consider 80% AMI or less rents as unaffordable in context of San Antonio’s true median wage.

“Eighty percent though, that’s not affordable,” Meyer said. “Because the people that really need affordable housing, they’re not in that AMI.”

[ Editor’s note: You’ll hear more from Miramontes and Meyer in an upcoming analysis on workforce housing. Also, there’s a mind blowing aspect that’s too complex to explore here, but that has to do with how rent limits compare to the median income of specific areas of San Antonio. We’re mostly talking about downtown, which is intrinsically pricey. But how do these prices hold up in poorer communities? ]

If HUD’s rent limits seem skewed, it’s because the formula is based on AMI, which has its own convoluted method.

We recently explored AMI in depth, in an analysis that looked at how surrounding, more affluent communities tilt the AMI upward for San Antonio, which is the poorest large American city.

Here’s a look at area median income chart for the San Antonio-New Braunfels area.

Forget the Friedrich for a second. If you’re looking to rent a subsidized apartment that’s reserved for a single-person making 60% of the area median income, that’s $30,240. According to HUD, the developer can charge you up to $756 for a studio or $810 for a one-bedroom.

However, it doesn’t add up if you do the math.

Take $30,240 after taxes [12% according to the current income bracket] divide that by 12 and you get $2,217, or the amount you pocket per month. HUD’s definition for affordable housing is 30% of a household’s income [which is its own pandora’s box to be opened another day]. Thirty percent of $2,217 is $665—well below HUD’s rent limits of $756 for a studio and $810 for a one-bedroom.

Then there are restrictions on what percentage of a tenant’s income a developer can charge—if you can call them restrictions.

The Flats at River North, which is under construction at Broadway and Jones Avenue, is a partnership between the San Antonio Housing Trust and NRP Group, a Cleveland-based developer with a strong presence in San Antonio. Again, the trust’s involvement means NRP Group will benefit from not paying property taxes.

In return, NRP Group will price half the units below market rate: 10% for people making between 50% and 60% AMI, and the rest for households at or below 80% AMI.

Of those below market-rate apartments, NRP Group can charge up to 35% of the tenant’s income, 5% above HUD’s standard for affordable housing. The rent cap was negotiated between the trust, which is ultimately voted on by the trust’s five-council member board, and the developer. For someone making in that 50% AMI range, $32,400 for a family of three, for example, 35% of their income could be considered excessive. The counterargument is that if the adults work nearby, they can save on transportation costs, which is valid and the reason I paid well more than 30% of my paltry newspaper income when I lived at the Brady Tower downtown while working at the San Antonio Express-News.

There is more, there is so much more … to be explored another day.

Ben Olivo is editor of the San Antonio Heron, a nonprofit news organization dedicated to informing its readers about the changes to downtown and the surrounding communities. Former Heron intern Carson Bolding contributed to this report.

Stay on top of San Antonio news and views. Sign up for our Weekly Headlines Newsletter.