Last September, a construction crew working on the $135 million renovation of the Children’s Hospital of San Antonio dug up bones, the first of what turned out to be the human remains of an estimated 70 people buried at the downtown campo santo sometime between 1808 to 1860.

While they confirmed dozens were likely still interred at the site of the San Fernando Cathedral’s old cemetery, where indigenous people and some of the city’s earliest settlers were buried, the Christus Santa Rosa Health System quietly filed for court approval to relocate the remains – all without telling the descendant groups of the people buried there.

The hospital paused that effort this week amid pressure from those groups, which had urged officials not to disturb the 200-year-old graves. The hospital now says it’s exploring a redesign that would leave those remains in place.

“We’re very hopeful on our end that this site will finally be respected the way it should have been for years now, as the campo santo of the early settlers of our city,” Ramon Vasquez, executive director of the American Indians in Texas at the Spanish Colonial Missions, told us on Monday.

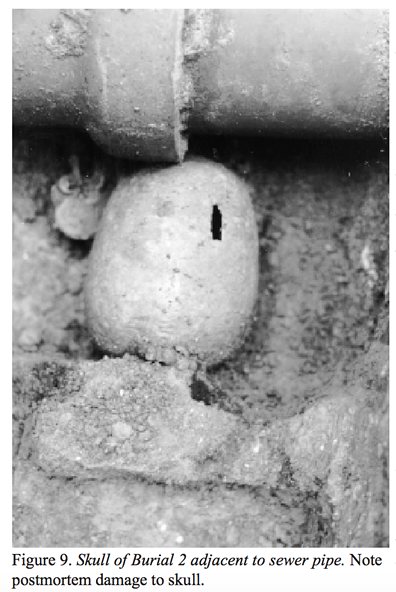

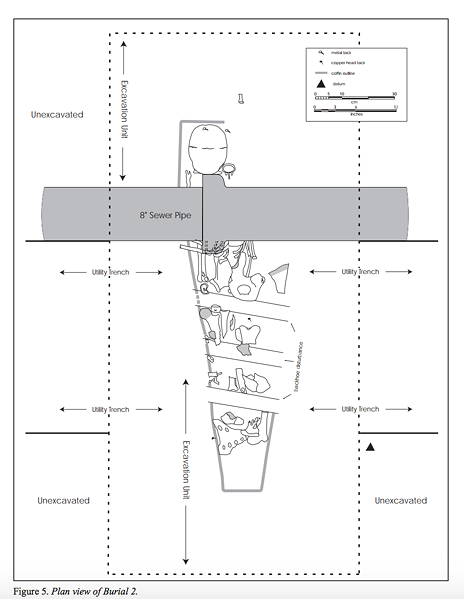

That bodies would still be buried beneath the Christus Santa Rosa hospital complex shouldn’t have been all that surprising. While city leaders in the mid-19th Century vowed to relocate remains at the site, it seems they never entirely finished the job. In the late 1990s, diggers on another Santa Rosa construction project found bone fragments that archeologists at the University of Texas at San Antonio later determined belonged to a man, woman and maybe even an infant. They ultimately found two coffins, one of which had been partially crushed by a sewer pipe. Due to “the possibility of encountering more burials” on the hospital grounds, the UTSA experts recommended monitoring and archeological testing before any future construction on site.

It’s unclear why that didn’t happen before this latest round of construction at the hospital. “Just about every time they stick a spade in the ground at Santa Rosa they’re dealing with human remains,” Vasquez said. “This shouldn’t have been a surprise discovery. They should have planned for this.”

When a crew excavating the site of Santa Rosa’s new prayer garden found bone fragments last September, the hospital system again called in UTSA researchers to scour a strip of land on the hospital’s eastern edge. Had the bones been discovered in construction across the street at Milam Park, where the park’s namesake and leading figure of the Texas Revolution is still buried, the Texas Historical Commission would have stepped in to monitor things per state law. But since the hospital complex is private property, the agency could only act in an advisory role.

As the Express-News first reported, this past spring the hospital system secured a court order that overturned the property’s cemetery designation and allowed for the “removal and reburial of all remains identified pursuant to UTSA’s explorations.” Descendants of people buried on site were furious when they found out about plans to remove the remains.

Some of the descendant groups finally sat down with hospital officials late last month in what was apparently the first-ever meeting of its kind. In an email Monday, Christus Santa Rosa spokesperson Melissa Krause told us that the “court-ordered removal of remains continues to be paused” while hospital officials work on a prayer-garden re-design “that would not require the removal of remains.” She says the hospital is working with descendants’ representatives on the plans. The trenches that were being dug on the building’s east end, where the latest bones were found, “have been covered with a layer of light sand,” Krause told us in her email.

Vasquez told us he hopes this latest dustup over centuries-old remains marks a turning point in the city’s history of development – one that respects the city’s earliest grave sites. In recent decades, his group has twice had to rebury remains of the early mission inhabitants, bodies that were dug up and moved when the Archdiocese of San Antonio let archeologists excavate part of Mission San Juan in the late 1960s.

“Nobody should be in the business of reburying the dead,” Vasquez told the Current.

Vasquez says he's still bothered by an image included in a 1999 UTSA report, from the last round of archeological study on the Santa Rosa site. It shows a sewer pipe that was placed on top of a human skull.

“Whoever laid that pipe, whenever it was put there, they had to have seen the body was sitting right there,” he said. “Maybe now we can finally give that space the reverence it deserves.”