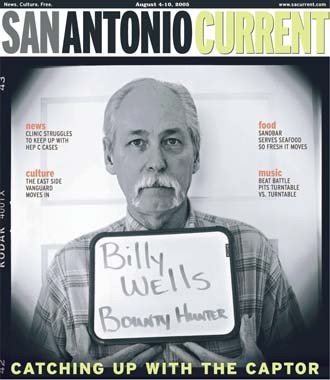

If you're on the lam, beware: Bounty hunter Billy Wells can find you

The one-armed bail skipper screamed for her "daddy," as Billy Wells, a local bounty hunter maneuvered her into the car. A "friend" had ratted out her location to Billy, and he found her outside a church getting ready for a wedding.

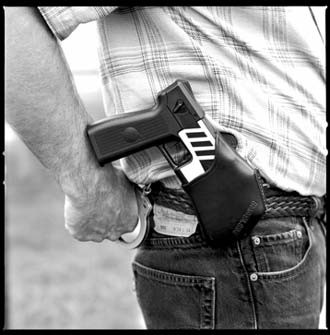

"Let my wife go," daddy hollered behind the tussling twosome. Billy turned around to see daddy holding an ax above his head, horror-movie style. So Billy just showed daddy his gun.

"He decided he shouldn't have brought an ax to a gunfight," says Billy, who routinely shows the weapon he carries for "self-protection" to anyone violently interfering with the apprehension of one of his bail skippers. "All I have to do is invite them to play."

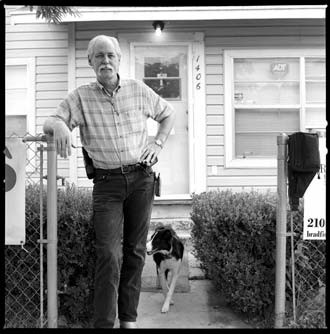

| Though bounty hunter Billy Wells has had more than 600 hours in law enforcement training, he prefers to work behind the County Courthouse in a house-cum-office to track down people accused of a crime. He says, "I'm not a cop, don't want to be a cop." (Photos by Mark Greenberg) |

Bounty hunters are stereotypically law-bending Texas Ranger types who look like they've just been thrown out of the toughest biker crew for being too ruthless, but that's not Billy.

He resembles a modern-day Gus McCrae from Lonesome Dove, a storytelling, nose-to-the-grindstone, rough-and-tumble Texas boy with a dominating and charming soft side. A boot-clad, Lubbock native, he sounds like a smarter Hank off King of the Hill.

Billy's business, Aaron Cash Back Bail Bonds, is housed with his two other businesses, Pronto Process, a company that offers skip tracing, video surveillance, asset recovery, and investigations, and Bodyguard Security and Investigations, behind the Bexar County Courthouse. Billy is a licensed private investigator and bail bondsman; legally, there are no "bounty hunters" in Texas.

He's always been self-employed; he owned and operated a high-rise window cleaning business for about 20 years. In addition to his San Antonio storefront, Billy has a home office. Although it isn't open 24 hours a day, calls are transferred from his San Antonio office to his Hill Country home throughout the night. "Just when you think you're going to have a relaxing meal at home, the phone rings and you've got to go back to the office," Jan, Billy's wife, says.

Banners advertising the businesses outside are the only reminders that you're not visiting grandma when you pull into the driveway. Sadie, a friendly 7-month-old border collie with one brown eye and one blue eye, first greets anyone entering the front office, which previous residents knew as a living room. The pup, a Valentine's Day gift from Billy to Jan, makes the trip to the office every day with the couple from their home. Jan, who runs the office ("She's the boss," Billy admits), is likely to offer you one of the seven or so kinds of soda or a snack in the kitchen/break room. And Shawn, the couple's son who also works in the business, is probably using his computer in the corner. The office isn't on the main strip of bail- bonds businesses in San Antonio, on West Martin where Gabriel Bail Bonds and A-Copa Bail Bonds sit. "We don't fit in there," Shawn says.

Billy's place is like somewhere you'd stop to see a friend, not where you'd expect to find a mother seeking the money to bail her 17-year-old out of jail, or those who have already been bailed out paying down their debt.

"We don't judge anyone who comes in here," Jan says. "Everyone is innocent until proven guilty. That's the way you have to look at them when they walk through the door."

But the Wellses are still cautious about the people they deal with.

"You're betting on losers for the most part," Billy says. "They just get in trouble over and over."

Bail, the amount of money deposited with the court on behalf of the accused person as an assurance that he or she will return, is determined by a judge. If the defendant does not appear on the assigned date, the bail money is kept by the court. A bail bondsman, who fronts the money, usually charges the borrower a fee of 10 percent of the bail amount. A judge also issues a warrant for bail skippers.

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, in May 2000 an estimated one-third of defendants who had been released from jail on bail or recognizance and were facing state felony charges were either rearrested for a new offense before their court date, failed to appear in court as scheduled, or violated the conditions of their bail, thus revoking their release.

| "Once you start going after them about the money, they start saying, 'I don't have the money, but I know where he is.' There's no loyalty among thieves." - Billy Wells |

The same study showed that of the 62 percent of defendants who were granted bail, about one-quater failed to appear in court by their assigned date, and 6 percent were still fugitives after a year.

"`The police` have a theory that these people who get in trouble will get in trouble again," Billy says. "And if it weren't for that, there wouldn't be a bail bondsman in San Antonio that could make any money."

The Texas and U.S. constitutions guarantee the right to bail, though in the case of capital offenses or the most heinous crimes, a judge can deny it. Most of those released on bail are accused of misdemeanors such as possession of small amounts of marijuana or assault without bodily injury.

"The police can't do much for a misdemeanor," he says, explaining that the warrant for arrest for failure to show up to court does not grant police the right to enter the accused person's home. "The police have to catch you outside, so the person can just look out the widow and stick their tongue out."

Law enforcement only works with bail bondsmen to apprehend bail skippers if the bail bondsman informs police of the accused's location and description. "We really don't work with bailbondsmen," SAPD officer Joe Rios says, but, he adds, "we will arrest anyone brought to our attention." Rios also maintains that the police treat every warrant the same, though they take special actions on capital-murder warrants.

Billy commends the police for helping to re-arrest felony-charged bail skippers, but this leaves a lot of the responsibility on bail bondsmen to track down bail jumpers who are charged with smaller crimes, primarily because they have a monetary investment in their return. If an accused person fails to appear on their assigned court date, the bail bondsman must pay the entire bail instead of just the 10 percent deposit required when the defendant was released. To keep tabs on their clients, the Wellses require a weekly telephone check-in from those for whom they supplied the bail money. If a client fails to check in for three consecutive weeks, the Wellses ask the judge to issue a warrant, and the bounty hunting begins.

A client of a bail bondsman in Dallas, recently jumped bail and fled to Mexico. Risking a loss of $250,000, the bail bondsman called Billy, who is known for returning bail skippers from south of the border. Billy contacted his Mexican associate, who, within a few months, had located the target. "We don't know how he does it," Billy admits.

Billy then paid the Mexican police upward of $4,000 to arrest the bail jumper. "We have to pay everyone in Mexico," Billy says. "They all have their hands out."

He also proved to Mexican authorities that the apprehended man was a U.S. citizen, prompting them to deport him. The FBI waited at the border for the murder suspect, who is now in custody in Cameron County. Billy never left his office.

"If I can have the police arrest them, I will," he says. Billy prefers to simply track down the individual.

Locating the target usually begins by finding whoever co-signed for the bail money (cosigners are always required).

"Once you start going after them about the money, they start saying, 'I don't have the money, but I know where he is.' There's no loyalty among thieves," Billy says.

But if a cosigner refuses to help with the search, the Wellses aren't left empty-handed. They often run "wanted" ads in the Thrifty Nickel that include their clients' photos, but they also use trickier methods. "We have our ways of having these people call us and make an appointment," Billy says. "They don't know they're making an appointment to be arrested."

Texas law grants private investigators who are licensed by the state the ability to arrest bail skippers and take them to the nearest holding facility. "We can't ride them around in the back of our car," Billy jokes. Investigators can be licensed after completing a four-year degree in criminal justice or through work experience as a peace officer or an insurance adjuster. Billy received his license through work experience, aided by a natural knack for investigations.

Using various internet services and public-records searches, with a first and last name Billy can find an individual's address, telephone number, Social Security number, and the vital statistics of those with the same address, which usually includes family members. "Everybody leaves a trail, and anyone can be found given enough time and money," Billy says. "This is really what I like to do. Sit right here `in my office` and find them."

"He'll pull 500 pieces of paper off of the computer and say, 'Figure out where they live.' I don't have the patience to find them, just the patience to be mean to them," jokes Jan, who handles the weekly telephone check-ins.

Billy also teaches others how to be an investigator. He sells an 18-hour video detailing the techniques of good bounty hunting and a tutorial CD-ROM about skip tracing. He also serves as executive director of the U.S. Professional Bail Bonds Investigators Association, a networking resource for bounty hunters worldwide.

The action has toned down slightly for Billy since the ax incident a few years ago: He's traded his firearm for a taser gun, but he's still inviting his targets "to play," though it may be a different game.

"I'm a gambler," Billy says. "I'm bettin' they'll go to court and if not, I'm bettin' I can catch them. People want me to go to Vegas with them, but I say, Why? I gamble here everyday." •