In the history of the conservation movement, notions of wilderness have rarely included people. Homo sapiens were universally tagged as the hapless despoilers of the land. Nearly 30 years ago, writer Gary Paul Nabhan exposed a notable exception to this ingrained prejudice by examining two desert oases â?? A'al Waitpia, located inside Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in Arizona, and Ki:towak, across the Mexican border.

De-peopled of Tohono O'odham subsistence farmers by the U.S. Parks Service in 1957, A'al Waitpia had since chocked on sediment, Nabhan wrote in in The Desert Smells Like Rain. It had regressed to a quiet pond visited by few animals or people. Across the border, at Ki:towak, fruit trees bloomed and insects rushed about thanks to the irrigation that made use of still-flowing springs. Native greens and healing herbs grew, and biological surveys showed human partnership with the land resulted in double the variety of bird species present.

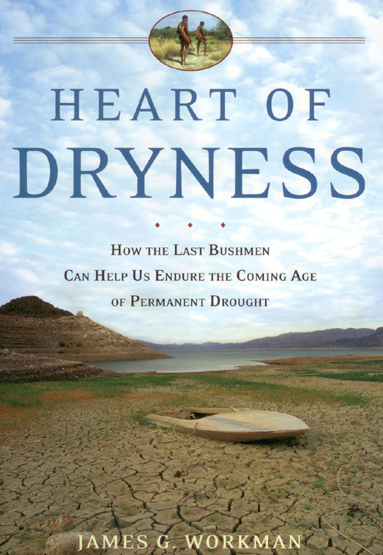

On a larger scale, the Parks system had long past driven out Lakota, Crow, Blackfeet, and Miwok from enormous parks like Yellowstone and Yosemite to preserve this “virgin” country. So it was with “First World” historical precedence and the tacit approval of the global conservation movement that the government of President Festus Mogae began to drive the Bushmen of Botswana's Kalahari Reserve off their land while exploiting global affection for the “animal-rights darling and antitrade emblem,” the African elephant, writes James Workman in Heart of Dryness: How the Last Bushmen Can Help Us Endure the Coming Age of Permanent Drought.

In this well researched and carefully footnoted offering, Workman not only exposes the suffering the practice brought to First Peoples fighting for liberty in the Kalahari, but argues that our increasingly thirsty world desperately needs the knowledge of those we persecute in the name of saving the Earth.

Workman's' 247-page narrative tracks the unraveling of what had been one of the most successful democracies in Africa as former President Mogae presses for the total removal of the few remaining bands of subsistence hunter-gatherers attempting â?? during what turn out to be the planet's hottest years on record â?? to hold onto their traditional ways.

Though many human rights organizations mobilized against Mogae's effort to drive Bushmen from the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, Workman suggests it was winked at by American and European wildlife biologists. After all, in protecting the over-sized elephant's wide-ranging habitat entire ecosystems hosting untold numbers of other plant and animal species are preserved, as well. For Botswana, there was nothing quite like Loxodonto Africana for the balance sheet: with tourism-related revenues climbing in pace with the growth of the elephant population. “The trouble with indigenous people, it seemed,” Workman writes, “was that they generated insufficient cash flow, especially foreign exchange from ecotourists.”

But it wasn't only elephants and tourist dollars motivating Mogae's government to shut down the sole federal water pump inside the CKGR and sustain a low-intensity war upon the Bushmen. The world's largest diamond company, De Beers, also reportedly had its eye on the Kalahari for new mining sites. In a nation and region where native peoples were frequently relocated to make way for development projects, the case against the Bushmen was exacerbated by the inherited racism of the dominant Tswana, many of whom ridiculed the Bushmen a “serf” class or as embarrassing “Stone Age” creatures. “If the Bushmen want to survive, they must change,” Mogae had said in 1996, “otherwise, like the dodo they will perish.”

Workman uses the story of resistance to tell a broader story about the gathering global water crisis that is already recasting international â?? and, perhaps more importantly, intra-national â?? relationships around the planet. Ultimately, Workman's tale is a rallying cry. It is a call to trade in our leaky, centralized water systems, massive pumping of irreplaceable fossil water, and food production systems soaking up seven of every 10 gallons of water worldwide (as much of the world slips into a state of permanent drought), with a decentralized model based upon key Bushmen principles.

He turns the tables on centuries of hydrological thought to ask, “What Would the Bushmen Do?” The answer â?? to Workman's mind â?? doesn't flow from a UN resolution establishing an inherent human right to water. Neither does it come through privatization. Instead it sits somewhere like a submerged Kalahari sip well, beckoning us to part the sands, fashion our reeds, and reevaluate the value of life itself.