Nearly 400 volunteers convened during one of last month's torrential rainstorms to conduct a census of those living unhoused on San Antonio's streets. I accompanied those doing the count, unsure of what I might find in a city with a growing unhoused population and overburdened resources.

Braving the weather, volunteers compiled data used to better understand the state of homelessness in the city and help local officials obtain federal funding to address the issue. Those conducting the count heard the stories of those living on the street, putting faces to hard, cold statistics.

The data, collected Tuesday, Jan. 23, as part of the annual Point in Time (PIT) Count, won't be available until May, but the night provided snapshots of San Antonio's unhoused population and showed the conditions often faced by those without shelter.

I last participated in a Point in Time Count 10 years ago in New York City, where I worked for a network of homeless shelters. I vividly remember canvassing the subway stations and streets of Manhattan's Financial District on foot in near-freezing temperatures. This was my first Point in Time Count in San Antonio.

The nonprofit Close to Home, formerly South Alamo Regional Alliance for the Homeless (SARAH), organizes the local PIT Count. As required by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the count always takes place in the last 10 days of January with the goal of assisting those experiencing street homelessness during winter weather.

"The PIT Count is an opportunity to check on our unhoused neighbors," Close to Home Executive Director Katie Wilson said. "Some homelessness is visible, yet other times it is hidden in plain sight."

Numbers recorded during the San Antonio count were likely affected by the previous day's record rainfall, during which floodwaters swept away people camped in drainage tunnels, according to eyewitnesses. The heavy rains continued as PIT Count volunteers combed the slick, shining streets, searching for those living unhoused.

Last year's Point in Time Count recorded 3,100 people experiencing homelessness in Bexar County, a 5% increase from the previous year.

An even more grim statistic: 322 people died in San Antonio last year while living on the street, according to SAMMinistries. Among those was Albert Garcia, a man who lost his legs due to 2021's Winter Storm Uri before dying in the August heat under a West Side highway off-ramp.

Canvassing and counting

Before the Jan. 23 count got underway, Mayor Ron Nirenberg spoke to the volunteers at Corazon Ministries Day Center on the city's work to improve the availability of affordable housing. Many of those improvements come through the city's $150 million Affordable Housing Bond, which includes $31 million for permanent supportive housing.

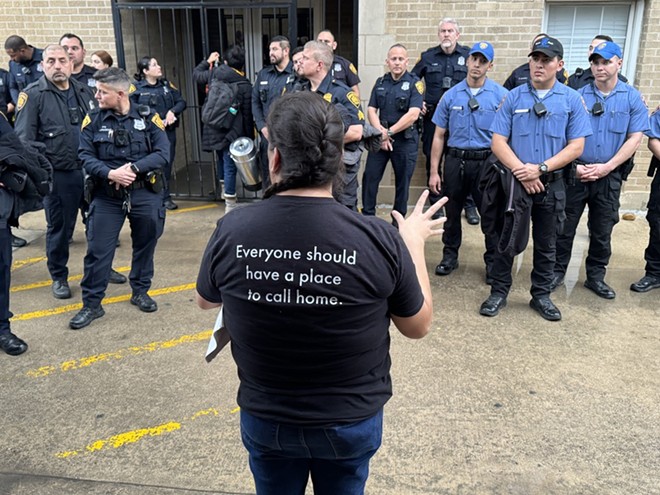

Activists note that this year's PIT Count numbers will likely be affected by the city's ongoing encampment sweeps, which routinely remove unhoused people, throwing away their tents and possessions. While local officials paused the evictions prior to the count, they were scheduled to resume at its conclusion — a fact not lost on some in the audience.

Toward the end of Nirenberg's talk, one activist shouted him down, calling on the mayor to end the encampment sweeps "if he really wants to help homeless people."

With the speech over, volunteers dispersed throughout the city, canvassing the streets in teams until midnight. Each group was assigned a police escort and zone to cover.

Volunteers asked people living on the street if they'd be willing to answer survey questions. Teams also handed out backpacks full of snacks, gloves and toiletries to those they encountered.

Separate from the volunteer-based street canvassing, outreach workers conduct an encampment count in the early morning to catch people before they break camp for the day. Closer to Home also conducts a tally of those living in the city's shelters. The totals are compiled to provide the most accurate picture of homelessness in San Antonio.

Resources 'on diversion'

Initially, I followed a team in Northwest San Antonio led by Katelyn Underbrink, a volunteer who works as a project manager in her day job.

A middle-aged man without a coat crossed a rain-slicked Jackson-Keller Road to approach the team outside a fruteria. He said he was suicidal. The team's escorting police officer drove the man to Restoration Center, a crisis mental health facility run by the Center for Health Care Services (CHCS).

Later, we learned the man had been turned away. Like many programs in the city, Restoration is "on diversion," meaning it's full.

The city's shelter system has been pushed past its limit and now has a waitlist of more than 3,000 households, according to Close to Home officials. That means PIT Count volunteers face difficulty finding immediate shelter and services for those they encounter, jeopardizing one of the purposes of the count.

The city's Strategic Housing Implementation Plan (SHIP) has identified a shortage of 91,000 units of affordable housing in Bexar County. That shortfall produces a cascading effect of systemic failure and maxes out the shelter system, leaving many out in the cold, according to advocates for the unhoused.

Challenges on the street

Later in the night, I fell in with a team led by Greg Zlotnick, a visiting clinical assistant professor of law at St. Mary's University. In addition to serving as a Close to Home board member, he specializes in eviction prevention and landlord-tenant disputes.

Zlotnick was joined by Michael Ozuna, who works as a Home Depot supervisor by day but said he has personal reasons for helping out.

"I've experienced homelessness and addiction, so I know what recovery is and I know what is possible," he said. "Anything I can do to help someone going through what I went through."

Zlotnick's team combed a zone of downtown bordered by the I-37 access road to the east and the River Walk to the west. It stretched from Brooklyn Avenue to Jones Street.

Over two hours, Zlotnick and Ozuna encountered a dozen or so people living on the street, including Renee Olivarez, a middle-aged man camped under the awning next to a funeral home. He was surrounded by bags of possessions with an umbrella propped up over his pillow.

Olivarez told us he lost his job and became homeless during the COVID-19 pandemic. His felony record made it hard for him to find new work even as the economy picked back up again, he explained.

Nearby, we found a blonde woman named Katrina wrapped in blankets. One of the blankets moved, revealing a pit bull puppy named Storm, swaddled and sick with a stomach bug. Katrina gently stroked her pet's face and asked Ozuna if he knew of any free veterinary clinics. Though Katrina was without a bed herself, she had a small, fluffy dog bed for Storm.

A few paces away, twenty-something Josiah Thompson crouched in a hooded camo jacket, organizing a bag of medicine. Once a dishwasher at an Alamo Drafthouse, Thompson — who goes by "Wolf" — opted out of society and into a life on the street.

When Zlotnick asked him about the challenges he faces, Wolf simply replied, "Isn't that a rather existential question?"

Many of those we encountered said their lack of IDs and paperwork were major hurdles in obtaining housing and employment. Others listed mental illness and addiction as underlying issues.

Dreams and nightmares

Zlotnick's team entered the River Walk at Brooklyn Avenue and took it north to Jones Street. The warm glow of lights from luxury apartment buildings offered a jarring contrast to the reality of people curled up on the pavement blocks away.

"The American dream and the American nightmare walk past each other," Zlotnick remarked, remembering the words of an old law professor.

As the night went on and the rain continued, our police escort — an officer and a cadet — urged us to end the night early, citing safety concerns.

"Yeah, and I can't help but think of the safety of the people who are staying on the street tonight," Zlotnick countered.

At the recommendation of their sergeant, the officer and cadet turned back for headquarters, and we continued our count without a police escort. At least one other team was abandoned by its escort that night, according to Close to Home officials.

When contacted for comment later, an SAPD spokesperson defended the officers' decision to turn back, saying it's dangerous for patrol personnel to stray too far from their vehicles.

Even so, the officers participating in the PIT Count had been given the choice to drive or accompany on foot.

San Antonio's unhoused population has a fraught relationship with law enforcement, especially after the highly publicized incident in which since-fired Officer Matthew Luckhurst was disciplined for giving a feces sandwich to a homeless man in 2016.

Close to Home is addressing the dynamic by working with local law enforcement to incorporate a trauma-informed approach into interacting with the city's unhoused population.

As midnight approached, the remaining teams returned to the Corazon Center to turn in their flashlights and report back on their experiences. Judith Andrade, Close to Home's domestic violence system and training coordinator, said goodnight to her coworkers and left the center with her brother, Ozuna, whom she says she "couldn't be more proud of" for beating addiction and leaving behind a life on the street.

Ozuna exemplifies what Andrade frequently shares in her training seminars: "homeless is a temporary condition, it's not what a person is."

Subscribe to SA Current newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter| Or sign up for our RSS Feed