|

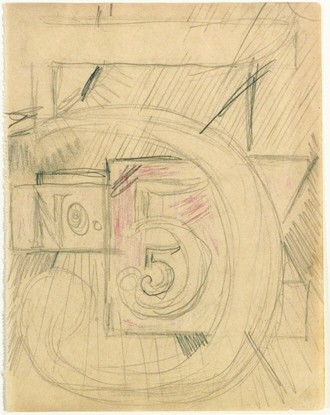

Two of the artworks the Tobin Endowment is selling to meet its $5-million pledge to the McNay: Charles Demuth’s Study for “I Saw the Number 5 in Gold” (1925-26), top, and Georgia O’Keeffe’s 1916 watercolor, “Blue I.” |

This passage from James Elkins’s Pictures & Tears recounts a 1967 visit by art historian Jane Dillenberger to Mark Rothko’s studio. The paintings that moved her so were Rothko’s giant, seductively dark “stations,” commissioned for what would become known as the Rothko Chapel at Houston’s Menil Collection. Dillenberger’s reaction explains how people can develop a special relationship with a work of art — as if, whatever the property laws might have to say about it, it belongs to them, or to all of humanity.

The story suits one of our subjects today, Georgia O’Keeffe’s “Blue I,” a deceptively simple curl of indigo, a sea shell becoming an entire wave. Like Rothko’s “stations,” it relies on the power of a singular palette and the emotion that is conveyed in the paint’s record of the hand to connect with its viewers. It is also significant in the artist’s career: painted in 1916, during O’Keeffe’s early mature period, it shows the focus on color and nature’s built-in erotica that would make her signature leaves and flowers solid-gold hits. Like Rothko’s work, it and its companion, “Blue II,” have inspired passionate responses, but unlike Rothko’s masterpieces, it is temporarily out of a home.

In January, “Blue I” was shipped along with 52 other works of art from San Antonio to Christie’s New York, where it is being prepared for sale May 24 as part of an auction titled “Important American Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture.” All of the items will be sold in five auctions between May and September and are expected to raise $1.8-2 million. The proceeds will be used by the artworks’ current owner, the Tobin Endowment, to meet a $5-million pledge to the McNay Art Museum’s $50-million capital campaign for a new building.

Yes, that Tobin Endowment.

It’s possible that the sale of the O’Keeffe, which was previously housed at the McNay along with many of the artworks now at Christie’s, would upset any San Antonio art lover — as would the sale of pieces by Joseph Stella, Robert Indiana, Christo, Jean Cocteau, and others that the Endowment is selling. But the artworks once belonged to the estate of Robert L.B. Tobin, the theatrical and theater-loving philanthropist who died in 2000.

Following in his mother’s footsteps, during his lifetime Tobin gave many important pieces to the McNay, including works by Henry Moore, Richard Stankiewicz, Cy Twombly, Kandinsky, George Grosz, Natalia Gontcharova, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Goya. His family’s donations account for more than half of the museum’s entire collection. Family members and their various trusts also loaned works to the museum or stored them there, further building public expectations that one day the McNay would be the recipient of all of the significant Tobin artworks.

But when Tobin died, almost everything that remained of his family’s estate was sold and/or concentrated into the Tobin Endowment, a charitable trust estimated to have assets worth $58 million at its inception. It is for all intents and purposes operated by one of its trustees, Bruce Bugg.

The Endowment had a stormy birth, beset with charges that Bugg and fellow attorney Leroy Denman exercised undue influence over an ailing Tobin and convinced him to rewrite business agreements and his will in their favor — allegations they adamantly deny. If there were a trial, the accusers would present a letter dated March 9, 2000, less than two months before Tobin’s death, that gives Bugg a $50,000 bonus, a monthly raise, and four percent “of the gross proceeds from any and all assets (not including marketable securities) sold by any of the various Tobin entities …” Compare Tobin’s signature on this document to a more circumscribed grant of power, commissions, and compensation from 1998, and the contrast is striking: Tobin’s handwriting is so markedly deteriorated that it has caused skeptics to question whether his competency was declining significantly in the last years of his life, when he was suffering from cancer-related complications. The will that created the Endowment and effectively transferred most of the estate’s assets to the trustees’ control at Tobin’s death was signed by Tobin in 1999.

The 2000 letter means that Bugg may stand to profit $72,000-80,000 from the sale of the artworks. Christie’s says that details of its agreements with clients are confidential. The Tobin Endowment did not return a call and an email asking whether Bugg would take a commission from the auction price. Bugg has referred all Current queries about the Endowment sale to Christie’s `See the end of the story for late-breaking clarifications from Christie's and Bruce Bugg.`.

Sharing the spotlight at the May 24 auction is a study by another early 20th-century artist, Charles Demuth. Although it is rough — simple graphite lines on paper —the stylized No. 5 that is the heart of Demuth’s most famous painting is clearly visible. The Metropolitan Museum of Art owns the finished work, “I Saw the Number 5 in Gold,” and for a time it seemed that the McNay might have its crucial counterpoint — but sometimes San Antonians don’t get to have their cake and eat it, too.

“We were offered a choice,” says McNay Director William Chiego: either the artworks or $5 million toward the capital campaign for the Jane and Arthur Stieren Center for Exhibitions, currently under construction on the museum grounds at North New Braunfels and Austin Highway. “We chose the cash gift.”

The McNay is in the middle of the biggest expansion of its 52-year history: 45,000 climate- and light-controlled square feet designed by Jean-Paul Viguier that will bring what has been an esoteric gem of a museum into the 21st century. Gallery space alone will increase by 14,000 square feet.

The Endowment also rationalizes that the artworks placed with Christie’s fall outside the scope of the McNay’s Tobin Theatre Arts Collection that became Robert Tobin’s passion. “The artworks that were donated in the past were focused on the theater collection,” said Allison Whiting, senior vice president and director of museum services at Christie’s. “As you know, `the sale of the artworks is` a choice that is supported wholeheartedly by the Endowment and, of course, by the board of the McNay.”

In the year before his death, however, Tobin did donate several artworks to the museum’s general collection, including pop artist Robert Indiana’s well-known “The Metamorphosis of Norma Jean Mortenson,” Paul Cadmus’s “What I Believe,” and three works from the early 1920s by James Daugherty. It’s a mystery why the O’Keeffe and Demuth were not among these gifts, but Whiting emphasizes that Tobin Aerial Surveys, not Tobin personally, purchased and owned the artwork (the Endowment did not reply when asked who owned the works after the company was sold in 1998 and before the Endowment was formed).

Another mystery: Why an Endowment valued in the mid-eight to nine figures needs to sell $2-million worth of artwork to meet a $5-million pledge?

The paintings, after all, may find a price at auction, but to art lovers — and one particular art lover with an axe to grind — they are priceless.

“`Robert` was so excited when he got `“Blue I”` that he bought the book — the big Georgia O’Keeffe book — and gave it to everybody for Christmas,” says Ann Tobin, Robert Tobin’s second cousin, who has been one of the most vocal critics of the Endowment and Bugg. “`The McNay` will never get anything like that again. They don’t have the funds for it, and it’s not available.”

Even accounting for Ann Tobin’s bias, these two works in particular fit the McNay’s strengths like machine-jigged puzzle pieces. O’Keeffe is one of the artists the museum brags on to boost its modern-art credentials. And rightfully so, since she is considered one of the most important artists of the 20th century, a pioneer of modernism who blazed the trail for Abstract Expression-ism among other movements. The McNay owns five works by O’Keeffe, including a watercolor from 1917, “Evening Star N. V.” Santa Fe’s Georgia O’Keeffe Museum lists “Blue II,” the near-twin of “Blue I,” as one of its prize possessions. Its outlines are familiar from Alfred Stieglitz’s famous 1917 photograph of the artist, in which she stands in front of the painting.

Ann Tobin loves to tell this story: Much later in her career, O’Keeffe wanted to buy “Blue I” from Robert. “He wouldn’t sell it back to her and she was furious.”

The Demuth is no less significant, being directly linked to the artist’s most influential work: “I Saw the Number 5 in Gold” is his “poster portrait” of William Carlos Williams. It takes its name from the writer’s poem “The Great Figure”: “Among the rain/ and lights/ I saw the figure 5/ in gold/ on a red/ firetruck/ moving/ tense/ unheeded/ to gong clangs/ siren howls/ and wheels rumbling/ through the dark city.”

Painted later in the artist’s career, “5” captures the hard, sharp, colorful language of modern urban life; its radiating, fractured shafts of dark red, blue-black, and gold are the bursts of energy pulsing from Williams’s angular, charged verses. In After Modern Art 1945-2000, David Hopkins credits Demuth’s painting with influencing no less an art giant than Jasper Johns. The study would have made a nice addition to the McNay’s growing “works on paper collection,” which already includes Demuth’s “Trees,” and “From the Kitchen Garden,” a beautiful and modern, if modest, still life from 1925.

But after May 24, other collectors or museums will enjoy “Blue I” and the study for “I Saw the Number 5 in Gold.”

“We had to choose one or the other,” the McNay’s Chiego repeats. “It was clear to me that the institutional priority was getting this building built.”

Note: The completion date for O’Keeffe’s “Blue I” and “Blue II” are variously given as 1916 and 1917. Christie’s and the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum use 1916.

After press time, Christie's emailed the Current the following clarification: