|

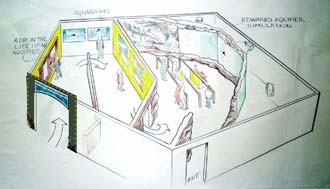

The Witte Museum builds a Water Resource Center Walking in the front door of the Witte Museum, one wouldn't know that the San Antonio River runs through its backyard. It's only once you are out the back door that you see it. The best view is from the H-E-B tree house, where you can look straight down into the water: On a good day you might see a stray turtle or snake, and ducks and geese generally mill about on the shore. This was also once the location of the Acequia Madre, which traversed the campus near what is now Pioneer Hall, and then flowed down to the Missions. A little to the north, lies the San Antonio Spring, also known as the Blue Hole; peer over its wall of porous vuggy rock and you'll find it really is a brilliant blue green, so crystal clear it makes one yearn for a swim (and, if you dip your hand in, it's not too cold). Just south of that, there's a sweet little footbridge that hangs over the very spot where the forks of the San Antonio Spring and Olmos Creek meet to form the headwaters of the San Antonio River. The water there is also inviting and vigorous, so clean you can see every rock and the swirling patterns of sand and vegetation. All this, and yet, historically, the Witte has not even been thought of as being on the river - let alone the same river that flows through downtown on the River Walk. "We really want people to think of the Witte from the point of view of the river," says Marise McDermott, president and CEO of the Witte Museum. "We are working very hard to figure out how we embrace the river. It's a thrilling challenge, but it's one that we have to approach carefully." To that end, the museum has budgeted more than $500,000 to the creation of a Water Resource Center. While it is still in the planning stages, McDermott says community support for the exhibition has been overwhelming; so far, the museum has 21 partners contributing funding, time, and ideas, including City Public Service, the Edwards Aquifer Authority, San Antonio Water System, San Antonio River Authority, Guadalupe Blanco River Authority, the Bureau of Economic Geology, Trinity University and University of Texas at San Antonio.

Arts and education institutions having been talking about water a lot this year. Last winter, the Southwest School of Arts and Crafts hosted an invitational exhibition called H20, Artists Consider the Hydrosphere, that brought together 30 area artists to talk about water in diverse media. One exhibit featured a video by Anne Wallace taken from a helicopter over a branch of the Brazos River. The film was then projected onto the floor, so that visitors felt as if they were in the air, while a soundtrack played the Troggs' "Wild Thing." In the spring, 13 arts organizations gathered in Houston for FotoFest2004, a film and video series that focused on "the extent of water's impact on creative expression." And, last month, UTSA's downtown art gallery featured an installation called Watercourse by Pennsylvania environmental sculptor Stacy Levy. Sponsored by 04Arts, Blue Star Contemporary Arts Center, SARA, and UTSA, the artist worked with inner-city school children to gather water from the city's rivers and creeks in plastic containers. Unadorned but for sand and the occasional stray leaf, the containers were arranged on the gallery floor in a deceptively simple map: The height of the containers revealed the size of the creek (short) or river (tall), while the number of containers in a row indicated volume, and the color of the water told its own tale. For instance, the water of Comanche creek was murky, while that of San Pedro Creek looked downright drinkable. Why all this attention to water, and why now? "It's part of our collective subconscious," says Paula Owen, director of SSAC. "In South Texas, our awareness of this precious resource is constantly part of our reality." Owen postulates that these exhibits provide a new way of communicating across disciplines - a more emotional, immediate way to explore ideas that are relevant to the community, and to bring them home for viewers who are not necessarily savvy to the language of science or politics. "Maybe it signals a kind of maturity in the arts that people feel they have the kind of credibility and vocabulary to address issues that are sometimes only addressed by politicians, scientists, and the government," says Owen. "Arts and culture is not a stand-alone dimension, it's a tool for experiencing all dimensions of life, everything." McDermott agrees: "It's very exciting when we can partner with people who have knowledge that is so specialized we couldn't possibly acquire it, but we can provide the public access and the interpretive strategy that allows the public to learn from it."

An 1836 map illustrates the path of San Antonio's seven acequias, which covered 15 miles and were used until around 1913, when population growth and fear of cholera spurred the development of private wells. Perhaps some mourned the loss; a 1927 pamphlet entitled "the Romance of San Antonio's Water Supply and Distribution," begins, "It was men taught by pain to know the worth of good water who founded San Antonio." (Espada, which is still used to irrigate gardens in the area, is the only functioning Spanish Colonial acequia in the United States.) Pre-dating the Spanish and their acequias, an 1800s Lipan Apache water basket further illustrates the idea that, until very recently, moving water was hard work. Although beautiful in the way that old things can be, rough hewn and soulful, it's not the most decorative tool: Made of straw and water-proofed with natural asphalt, it looks like a lumpy black ball and it weighs a ton. "As soon as we could turn on a tap we stopped thinking about how much water we are using, because we don't see the source: It seems an endless supply," says Haynes. "In truth, there's a finite amount of water, but we don't seem to have a finite number of people."

Stage two will also include a large mosaic of the watershed and river basin, set into the floor of the prow "so people can actually walk the river basin and look at how water flows." Witte Museum Director Mimi Quintanilla says the Water Resource Center is only a prototype, and that the museum plans to solicit public feedback and monitor how successfully the information provided helps inform, and in some cases change, viewer attitudes about water before building the permanent exhibition. What they hope to find is that people come away with a sense of ownership. "We've become so disembodied and spoiled in the way that we use our water resources that we've become less conservation minded and protective of that resource," Quintanilla says. "The main point is: there's a world of water, but only a minute portion of it is potable. And there's no new water, so we have to be conscious of how we use it." • By Susan Pagani

|

Tags:

KEEP SA CURRENT!

Since 1986, the SA Current has served as the free, independent voice of San Antonio, and we want to keep it that way.

Becoming an SA Current Supporter for as little as $5 a month allows us to continue offering readers access to our coverage of local news, food, nightlife, events, and culture with no paywalls.

Scroll to read more Arts Stories & Interviews articles

Newsletters

Join SA Current Newsletters

Subscribe now to get the latest news delivered right to your inbox.