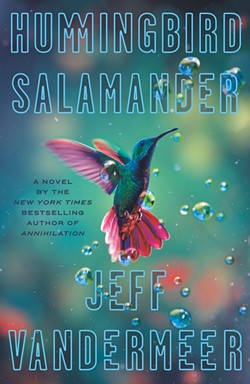

From the Southern Reach Trilogy to Dead Astronauts, Jeff VanderMeer’s award-winning weird fiction has long captivated readers. After making the jump to the screen with Alex Garland’s film adaptation of Annihilation, he’s now working with AMC on an upcoming television series adapted from 2017’s Borne, and Netflix has optioned his new novel Hummingbird Salamander — which hits shelves on April 6 — as a film.

Titled for two mysterious pieces of taxidermy, Hummingbird Salamander sends security consultant “Jane Smith” down a rabbit hole in the Pacific Northwest, as she unravels a mystery associated with a reputed ecoterrorist who also happens to be dead.

As part of his Hummingbird Salamander book tour, VanderMeer is making an online appearance at the San Antonio Book Festival on Friday. He’ll be joined by critically acclaimed author Silvia Moreno-Garcia (Mexican Gothic), with whom he shares an “absolute fascination with mushrooms and fungus.”

If we’re lucky, there may also be a special appearance by his enigmatic tuxedo cat Neo, who’s been known to gallop behind the author during Zoom events.

The Current connected with VanderMeer over Zoom to talk technology, ecology and a bit about feline inspiration.

Your Hummingbird Salamander book tour is entirely virtual. One aspect of online events is that they’re highly accessible — do you think you’ll try to maintain some level of digital access for appearances moving forward?

Well, there’s two different entry points to that question. The first one is that I’ve been trying with the virtual events to figure out what can be done to make them as personal as possible in terms of the interaction. Because there is that live component where I would normally get there before the event — I would be talking to readers who are there early and things like that. So, I’m going to do a few things for most of the events, when possible, to be in the chat room right before and during introductions. I’m going to have giveaways during the events and all kinds of other things. There’s a special tour website and things like that. So, there’s the aspect of how do we make the virtual world — differentiate it during the book tour from what it usually is.

But then on the other side, absolutely, because some of the things that we’re doing I would love to keep for the live events. For example, on a couple of tour stops we’re going to have a local wildlife rehabber with a bird talking about her experiences rehabbing hummingbirds, and there’s no reason why we can’t reverse that and have a live event where we have a screen with somebody coming in for five minutes to talk. So, I think that’s really important.

I think it is a really democratic platform in the sense that people can go to all these things that they might not have been able to otherwise for various reasons. So, I really hope that festivals keep this kind of component along with the live stuff. I think there’s a lot of interplay that’s really useful and makes the event better.

Are there any specific locations in the Pacific Northwest that contributed to the setting of Hummingbird Salamander?

Kelly Brenner’s a friend of mine, and she’s a naturalist in Seattle, so she showed me a lot of urban wildlife places including a really fascinating ecosystem right under a highway bypass. Then Damaris Brisco showed me Roy’s Redwoods, which is farther down toward San Francisco. In the novel, there’s both kinds of places — there’s places that have been destroyed by human beings to some degree and then rebuilt in terms of ecosystems and then places that are pure wilderness. In addition to that, one inspiration is just the drive down the coast. My last book tour was literally before the pandemic hit — in December of 2019 for Dead Astronauts — and I used that opportunity to do research. The main character Jane at one point is actually fleeing down the West Coast, so I method-acted that a little bit. I was going to the same places. There’s nothing that really replaces the tactile detail and actually being in that moment. I think that helped a lot.

You’ve said your cat Neo was an influence for both the cat Chorry in Authority as well as Mord, the giant flying bear in Borne. Can we look forward to a Neo cameo of sorts in Hummingbird Salamander?

I think because the character is on the move so much, I was reluctant to give them a pet because — and this is totally the readers' fault — so many people emailed me asking if Chorry made it out OK after he had to be abandoned [in Authority].

So, I felt bad, even though I thought Chorry probably made out better than some of the human characters and wouldn’t have done well if he’d gone along with Control. But yeah, I think for that reason I just didn’t, but I’m sure that’ll recur because Neo’s pretty much in everything at this point.

Yeah, I believe so. You know, it’s weird — it started out with it the way it did with Annihilation, because with Borne and with Hummingbird Salamander I haven’t even had to state “these are the things that I think really need to remain faithful” without wanting to get in the way of somebody else’s vision. The people that are involved with those projects, when we first had our meetings they said, “These are the things that are important for us to keep from your novel” — and they were the exact same things. So it hasn’t even come up. The people at AMC have been absolutely wonderful, and the Hummingbird Salamander process [with Netflix] is a little slower just because of the pandemic and when I turned the novel in. But they’re talking to people right now, and I have every confidence that both adaptations will be faithful in the things that I think are important with regard to the environment and all that.

Is there any difference in the process because Hummingbird Salamander was optioned before it was published?

It was remarkably generous of Netflix to option something based on 20 pages and a seven-page summary. I felt comfortable doing it just because I knew there was going to be a kind of cinematic feel to it to begin with — even with the interiority of character — and then also that the structure was going to be a thriller structure. There’s certain novels that I probably wouldn’t allow to be optioned until I’ve finished them, but this one, it didn’t seem to interfere with my imagination at all for various reasons, so there’s that. I wasn’t forced by Netflix to give them pages as I was finishing them or anything, so it was pretty much the normal thing, except that they optioned it earlier than you would normally see.

Now that you’re starting to see multiple of your works go from page to screen, does that affect your writing process at all, or absolutely not?

No, it really doesn’t. I mean, some novels are just going to be naturally more visual or more cinematic in how they present, and others are going to be less so. But I would say that, after Annihilation the movie, I think one reason that I wrote Dead Astronauts is because my subconscious was a little bit concerned about all the hype around the movie. I was a little concerned about possibly it affecting my creative process, and so my subconscious basically said, “Jeff, why don’t you write the least commercial thing you possibly can that reads mostly like a prose poem from the point of view of various animals?” (Laughs.) Thankfully, it’s actually done very well for an experimental novel, but I do think that was like the cleanse after the Annihilation movie process and all the commercial aspects of doing publicity for that and everything. It really helped me stay on track.

A major project that you’ve been working on for a while is rewilding your backyard. Could you speak about what led you to embark on that process, and the experience of working in tandem with your local ecosystem on its terms?

Oddly, it was in part because of Annihilation and the movie, because I got so many invites from science departments — environmental science classes and whatnot — to speak that I really began to question my own voice on that. Which is to say, how much do I really know? What am I doing locally, for example. So, that really helped me see where I had blinders on about various things, and one area was I didn’t really know as much about native plants as I did about native birds and other wildlife. When I started researching that, of course, that opens up all kinds of societal and cultural things. Native plants refers to plants that were native to an area before settlers came, and usually were part of indigenous land management systems. So, you learn a lot about that. You learn a lot about the fact that without native plants, wildlife just doesn’t have enough food, because those plants are adapted to being in existence with those organisms.

It’s been really amazing the last three years doing that. I thought on Twitter when I started posting about it that I would lose followers — I thought for sure that no one would care. And yet the most amazing, wonderful thing is that I gained like 30,000 followers over the last couple years, mostly because of the nature stuff. And I get so many emails and direct messages and stuff every week from people who are like, “I didn’t know herbicides were so bad for the environment,” “I didn’t know that fertilizer was actually bad for the environment,” “I didn’t know about native plants." Just like I didn’t three years ago. And in so many cases, I see it making a real difference in how people treat their own property or their own space. I get people who rent apartments, and they put wildflowers on their balcony, and in heavily urban areas like Atlanta, they see [that] a hummingbird that might be traveling thousands of miles has a place — a way station to get food, basically — along the way, even in a busy city. So, it’s been very rewarding, I must say.

After two years, one of the really wonderful native azaleas finally bloomed! For #FlowerReport #VanderWild pic.twitter.com/FQrIxEKXhl

— Jeff VanderMeer (@jeffvandermeer) March 28, 2021

What advice do you have for anyone interested in rewilding or at the very least integrating more native flora into their landscaping?

There are actually a lot of similarities between some of the plants in Texas and in Florida. There’s kind of like a migration path there, too. What I would say is first keeping in mind that you don’t have to rip out everything in your yard that’s not native. There are actual plants designated by the state of Texas, the state of Florida, that are classified as invasive non-native, and if you have those, those are the ones that you should probably worry about.

But the first thing you need to do is — whatever space it is — evaluate what’s going on there to begin with, because you can make a change and hurt wildlife by mistake because you just don’t know how things are being used. Second thing is to know that if you have at least 70% native plants in your yard or space that’s usually enough for the wildlife to do well. So again, you can kind of do it gradually.

And then also benign neglect is good: not raking your leaves, because that leaf cover is really important to birds for food, and things live in it, like fireflies when they’re not in their flying stage, so things like that. Just not doing certain things. Letting your grass grow long or letting your wildflowers grow instead of mowing them. I have a lot of tips on my website. I have a whole yard section, and I have links to articles.

With rewilding, it seems like you are working on a whole other timeline as plants become established and mature. Versus how we commonly get plants at nurseries that are already mature, or even blooming. Can you speak to the tension between how we want that immediacy versus being on that longer timeline of how growth really plays out for flora?

It’s kind of strangely like how I get in the middle of a novel, where I want to just turn to a short story, so I finish something quickly. (Laughs.) And have something to look at. But I think it’s seeing time in different ways, and also definitely trying to satisfy that immediate need to do something quickly. For example, the first thing I did is actually using Audubon’s rules for putting up bird feeders, because that’s the best way to avoid disaster with squirrels and things. I put up three bird feeders in different parts of the yard. That was so while the native plants were getting established I would be attracting more birds, and then slowly decommission some of the bird feeders as they found more natural food in the yard. That of course immediately brings birds to your yard. Then, also, you certainly can buy an assortment of plants, some of which — some wildflowers — will be blooming immediately, and then some that are more long-term projects.

I think having both a longer and a shorter sense of time is really important, because with the climate crisis, we see this huge process playing out, and feel like we don’t have control — wanting to help but still not realizing in the moment just how much we can help. So for example, a cardinal in the yard will likely live six years. No matter what happens with climate change, I’m pretty sure that with what I’m doing this generation of cardinals in the yard will never understand that there’s climate change. They will just have a good life. Some animals have a much shorter sense of time — the possums in the yard only live three years. So, you can do a lot of good for a lot of organisms in the short term that does have a lot of meaning, while also planting drought-resistant plants, looking forward to how the landscape is going to change in your area and how the temperature’s going to change, and anticipate that in some of the things you plant, so that you can be productive into the future in terms of helping.

Jeff VanderMeer in Conversation with Silvia Moreno-Garcia

San Antonio Book Festival

$32, 8 p.m. Friday, April 9, sabookfestival.org.

Get our top picks for the best (online!) events in San Antonio every Thursday morning. Sign up for our Events Newsletter.